By: Sam Kinsman

Ni Hao São Paulo. This Mandarin Chinese-Portuguese mixed phrase represents what has quietly become one of the world’s most significant international trade partnerships: the relationship between China and Brazil. In the U.S., all eyes are on China. It has shown extraordinary economic growth and overtook Japan last year as the world’s second largest economy after the U.S. Its 1.3 billion people—nearly 20% of the world’s population—have together become the third largest export market for the United States and its number one supplier of imports (19.1% of all U.S. imports in 2010, $365 billion). The value of China’s currency, the growth in Chinese military spending, and Chinese foreign policy (among other things) have all been regularly analyzed by Americans trying to determine their future impact on the United States. For some people, China’s new international status is best represented by the addition of the new China section to the Economist magazine, the first such country specific section added to the publication in the nearly 70 years since the U.S. section was added in 1943. However, it’s important to remember that China deals with countries besides the U.S. While China’s wealth, military, and international influence continue to grow, the myopic focus on merely Sino-American relations can leave the impact of China’s rise elsewhere relatively unexplored.

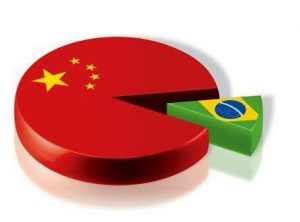

China’s growth has strongly impacted Brazil’s recent development as a major emerging economy. Brazil is the largest country in South America by land area (larger than the continental U.S.) and has the fifth largest population in the world. With its robust economic growth, it also recently passed the United Kingdom to become the world’s sixth largest economy. Total trade between Brazil and China has flourished over the last decade, with Brazilian exports to China growing 46.9% annually over the last twelve years and China replacing the U.S. as Brazil’s largest trade partner in 2009.

In few industries can the effect of this trade relationship be seen better than in Brazil’s agricultural industry. Specifically, it can be seen in the production of soybeans, which constituted over 31% of Brazil’s total exports to China in 2009. For those whose only experience with soybeans is limited to the vegetable in the supermarket, it can be surprising to learn how versatile this cash crop is in meeting the demands of a modern economy. Soybeans and the crop’s two main derivative products, soy meal and soy oil, are used in a variety of common food-related products including soy milk, tofu, shortening, margarine, cooking oil, and salad dressing. It is used as a major source of nonmeat protein and adds healthy oils and fiber to many people’s diets around the world. In addition, soy is also used in industrial paints, varnishes, printing inks, baby formula, and animal feed. China’s huge population and economic rise has led to a dramatic increase in the demand for soybeans to feed its population and livestock and for raw material to support its manufacturing processes.

If the famous economist David Ricardo were alive today, he would likely be cheering on the sidelines as he watched two growing nations expand their trade relationship. But how beneficial is China’s current trade with Brazil? It is clear Brazil will need strong international relationships to continue its own economic growth that has already lifted millions of Brazilians out of poverty. Despite this, the real impact of selling to China is beginning to be questioned by the leaders of Brazil. A closer look into the trade reveals that nearly 84% of Brazil’s exports to China are in the form of raw materials. In contrast, 98% of Chinese exports to Brazil are manufactured products, suppressing the Brazilian industrial sector. This clearly unbalanced trade resembles a neocolonial relationship in which Brazil is passing the upper hand to its East Asian partner. Chinese companies have taken even further steps to directly control the soybean production by buying large tracts of rural land in Brazil. This aggressive approach to increase the acreage of soybean production has already led to policy reforms in Brazil to limit foreign interests from controlling precious natural resource land.

If we turn our attention away from the direct relations between U.S. and China, we can begin to analyze China’s growing impact on the developing world around us. Does China’s rise impact Brazil? The answer is clear: more than ever before. But the impact of this growing trade relationship does have important implications for the United States. U.S.-Brazil relations have been tense for years over issues including Iran’s nuclear program and the status of Cuba, with Brazil consistently trying to show its independence from the world’s most powerful country. Brazil’s growing vulnerability to China as evidenced by its unbalanced trade will likely lead it to revalue its relationship with the United States. In support of this, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff is scheduled for an official state visit in April where she will meet with President Obama to discuss the growing partnership between the two countries. By many measures, the U.S. economy remains depressed and in need of new opportunities for growth. Trade with emerging economies can provide that opportunity if redoubled efforts to strengthen these relationships are made. At a time when political relations with two of the world’s fastest growing nations, China and Russia, are contentious over the issues of Syria, Iran, and North Korea, the U.S. should take every effort to strengthen its relationship with Brazil and secure its share in the growth of this beautiful South American nation.

Why, then, do Brazilian soybeans mean so much to the world? Because as its massive economy continues to grow, China puts increasing demands on its Portuguese-speaking partner. Demands which not only impact development inside Brazil, but the very dynamics of international relations around the world.