By: Aashka Dave

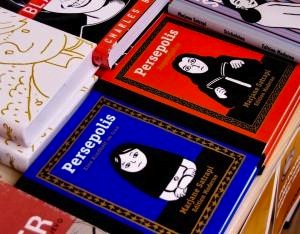

Normally when individuals think about censorship, oppressed countries and communities come to mind, not an urban metropolis in the United States. Yet Chicago Public Schools (CPS) drew the attention of the nation last week when the system attempted to ban the graphic novel “Persepolis: A Story of Childhood” by Marjane Satrapi.

Schools received word from CPS CEO Barbara Byrd Bennett Thursday that they were to remove Persepolis from libraries and stop instruction of the book.

The move sparked demonstrations, including a read-in at Social Justice High School and a protest at Lane Tech High School. The American Library Association (ALA) wrote a letter to Bennett, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, and David Vitale, President of the Chicago Board of Education, expressing its discomfort with the directive to remove student access to “Persepolis.” The ALA said the directive “represents a heavy-handed denial of students’ rights to access information, and smacks of censorship.”

The Chicago Teachers Union also released a statement following Bennett’s initial directive in which their spokeswoman, Stephanie Gadlin, said, “We stand with our educators who see this sudden book banning directive as an unnecessary overreaction.”

However, within a matter of days Bennett’s office released a second memo. This memo stated that it was never the office’s intention to ban “Persepolis.” Rather, they were interested in removing the book from general use in the seventh grade curriculum, having determined that “’Persepolis’ may be appropriate for junior and senior students and those in Advanced Placement classes” due to the novel’s “strong images of torture.” It would still be available in libraries though.

“Persepolis,” an autobiographical look at Satrapi’s childhood in Iran, does discuss controversial topics; it questions authority, racism, gender issues, class structures, and contains some violence. However, as Satrapi said in the wake of the directive, “These are not photos of torture. It’s a drawing and it’s one frame. I don’t think American kids [in the] seventh grade have not seen any signs of violence. Seventh graders have brains and they see all kinds of things on cinema and the Internet. It’s a black and white drawing and I’m not showing something extremely horrible. That’s a false argument. They have to give a better explanation.”

Apparently the initial directive sent out by CPS Network Chiefs was misinterpreted on a rather grand scale. “Persepolis” was not banned, merely restricted. However, this miscommunication, along with the current state of the book in Chicago schools, brings up a number of issues.

One of the most notable of these issues is the ability of students to still access Persepolis. As the CTU pointed out, 160 elementary schools don’t have libraries. Gatlin went on to say,“Enough with the Orwellian doublespeak. We support our educators who are fighting to ensure their students have access to ideas about democracy, freedom of speech and self-image. Let’s not go backward in fear.”

Are the CPS’ efforts to remove “Persepolis” still censorious, though? True, elementary school students may not have access to this book, but without school libraries, they may not have access to any books at all. The book is not being removed from schools, the curriculum is simply being adjusted.

However, according to the ALA, “censorship occurs when expressive materials, like books, magazines, films and videos, or works of art, are removed or kept from public access.” At the moment, “Persepolis” has certainly been removed from access, namely from the seventh graders who originally expected to read the novel as a part of their curriculum. Is CPS wise in removing “Persepolis” so late into the school year, when teachers may have already taught or made plans to teach the book?

More to the point, the restriction impedes student education, rather than aid it. Would it not be more effective to have parents sign permission slips regarding “Persepolis” rather than completely alter the curriculum? The issues “Persepolis” discusses are important ones; as Satrangi mentioned, students today do not live in a bubble. Most seventh graders know at least something of violence, and understanding what liberties other countries do (or do not) allow is significant to any education. Now, students will find it increasingly difficult to not only read the book, but to have their questions answered on its significant subjects as well.

More importantly, how did Chicago Public Schools manage to bungle communicating an issue of such magnitude? The issue of banned and restricted books often garners attention regardless of the country the censorship takes place in. When that censorship takes place in a country that greatly values free speech, the fallout will always be pronounced. Surely there were better ways to handle the situation, including writing to parents, sending out a more clearly worded initial directive, and addressing the issue before it became national news. That CPS failed to do any of these things not only brings into question their motives, but also the value they place on students’ education. Read-ins, protests, mid-semester curriculum changes, and media attention are all certainly disruptions of the education of Chicago students, disruptions those students do not deserve.

Ultimately, the CPS directives do restrict student access to “Persepolis,” and therefore fit the ALA’s definition of censorship. It is true that the book is not banned, but it has been restricted, and in the most unwieldy manner possible. The education of CPS students will change as a result, and that change is not a positive one.