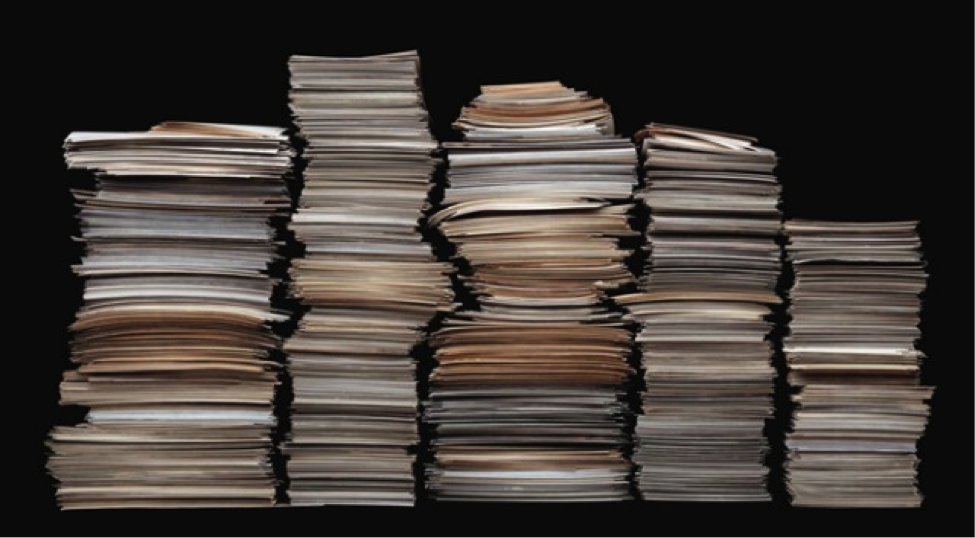

Think that your local congressman is a bit long winded in his campaign speeches? Try catching him at his day job where he and his colleagues are producing some of the longest and most complex legislation in U.S. history. Since 1948, the average number of pages in a bill has grown from two and a half to over 15, and Congress has increased its total output by nearly 5,000 pages. There has been outcry, praise, and utter bewilderment concerning lengthier legislation. The public is currently attempting to understand this complex and convoluted legislative strategy and discover how it fits into the model of a government accountable to the people. There is little transparency in these bills and, because of this, the public knows less and less about the job their representatives are doing in Congress. A well informed public is necessary for responsive elections and an effective legislative environment; lengthy bills are not conducive for either of these goals.

The problem of lengthy legislation began in the 1950s, when traditional policy bills became intertwined with budgets and other unrelated legislation. In order to pass controversial bills, powerbrokers such as Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson would attach riders to critical government funding bills in order to force them through. Conservatives took advantage of this in the 1970s by offering anti-abortion amendments to routine bills. Foreign policy hawks in the 1980s tied weapons sanctions to important trade bills. The integration of policy areas into singular bills continued into the 1990s. Brinksmanship legislating on budget matters required extensive deal making in a short amount of time and Congress had to consider a wide variety of interests in order to pass a budget. It was rare to see a spending provision passed that was under 1,000 pages and did not stretch across multiple areas of the federal government’s policy domain.

This remains true today as congressional gridlock has created an environment where passing a single bill is considered a victory. Naturally the ones that do pass are longer and contain more provisions. But gridlock and deal making do not tell the whole story. The Affordable Care Act only dealt with a single policy area and contained no compromise hidden within. It was still over 230,000 words. Political scientist Glen Kurtz attributes this to the increase in issue complexity since the New Deal. Since then, the federal government has expanded its scope and increasingly deals with complex administrative issues rather than broad mandates. Add that to the fact that Congress and its bill-drafting affiliates are dominated by lawsuit-conscious attorneys whose experiences with contracts have taught them to be as wordy as possible so that all their bases are covered. Then it becomes quite clear why the government needs more and more words and pages in order to craft a policy.

Lengthy legislating is renowned by some. Party leaders charged with the maintenance of Congress see it as a crucial tool for the upkeep of the institution in an era of a polarization. It gives individual congressmen the opportunity to vote to fund the entire federal government instead of a controversial program like the EPA or the NSA and, thus, avoid the wrath of their constituents. It is also well suited for complex policy areas that need to be nuanced and refined in their wording. Moreover, Congress is supposedly prepared for the lengthy bills. There are an unprecedented number of staffers on Capitol Hill available to help congressmen understand the provisions of densely-packed conglomerates like the ACA. Interest groups are also becoming an information source. They provide succinct summaries to both lawmakers and the general public who have neither the skill nor time to read lengthy, complex bills.

Detractors, however, focus on the lack of clarity and the likely possibility that members of Congress have little clue as to what is being passed in these massive bills. Reading through the legislation is nearly impossible. As former Congressman Don Johnson described “[It’s] like drinking water out of a fire hydrant.” Although staffers and special interest groups inform congressmen of the contents of bills, there is only so much that humans can do with such a large amount of information. Ample opportunity exists for party leaders to include hidden benefits for specific groups that the entire chambers might not support if they were aware of them.

Common Good is a political reform advocacy group that campaigns against the increasing length of legislation. It holds that long and complex laws move public policy out of the realm of the actual public and into that of technocrats. It also emphasizes that antitrust legislation and the Interstate Highway System were authorized in bills less than 30 pages long and proved to be two of the most effective in U.S. history. Legislators are not listening to groups like Common Good though. Since it was founded in 2002, Congress has passed several massive bills including George W. Bush’s 2007 budget compromise with congressional Democrats. It was over 600 pages.

Lengthy bills have seemingly become necessary in a world where Congress is hopelessly gridlocked. But they are more of a symptom of a problem than a problem themselves. The government is run by parties that cannot work together, so they are pushed into using unconventional and sometimes deceptive tactics in order to advance their agendas. However, lengthy bills have one unredeemable consequence that cannot be justified by their usefulness as a legislative strategy: They muddle the public’s perception of a popularly elected assembly.

It seems contrary to common sense that a government established to be accountable to the people would force citizens to rely on third party sources in order to understand its lawmaking. A transparent and accountable assembly should lower information costs for citizens and lawmakers. Congress has pursued some reform in this area. The Read the Bill Act from 2009 required members to have at least 72 hours to read bills. A different bill with an almost identical name, the Read the Bills Act, was proposed in 2012 and placed a one day waiting period on a bill for every 20 pages on legislation. It has yet to see action on the floor. Reforms like these are critical for enhancing citizens’ understanding of public affairs and removing the veil from Capitol Hill. A big step towards resolving the current plagues of polarization and gridlock is a well informed public that can discern what is happening in a session of Congress. Complex, lengthy bills are not the fix for a broken Congress. They isolate Americans from the political process and should be discouraged through reform legislation and by voters at the ballot box this November.

Other Sources

Kurtz, Glen Hitching a ride: Omnibus legislating in the U.S. Congress

In person interview with former Congressman Don Johnson