By: Uzma Chowdhury

While you are sitting somewhere, maybe waiting for class or on a bus, reading this article on your iPhone or laptop, take a moment and try to name a few American Indians from history. Pocahontas? Squanto? Sacagawea? Crazyhorse? The few of those that come to mind are horrifyingly stereotyped one way or another. The spiritual and wise friends and saviors of the white man who taught the pilgrims and explorers so much about nature and the world, or the, vicious, wild cowboy-killer from Western films.

The Disney princess who saves a white man via true love and nature, was in reality forced into an arranged marriage, baptized and renamed Rebecca. The peacemaker who broke bread with the pilgrims only knew English because he had been kidnapped, almost sold into slavery, and forcibly converted to Catholicism before being brought back to the New World for his famous rendezvous with the passengers of the Mayflower. Sacagawea was captured and sold as well before she became the companion of Lewis and Clark, not by her own choice but because her owner and the famous explorers struck a deal to have her serve as a translator for the journey: “A woman with a party of men is a token of peace” according to Lewis. Even Crazyhorse was fighting against the encroachment on the land of his people and a violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1868. He was killed by a bayonet in 1877 on his way to take his sick wife to his parents.

It is problematic that for the vast majority of those currently living in the United States, our knowledge of American Indians is limited to skewed and often incorrect stereotypes based on relationships with white men—good Indians who helped or bad Indians who killed. Even our very definitions of the few we do learn about depend, not on the people themselves, but on how they helped or hurt the explorers and colonists who wrote their stories. And perhaps this manner of learning the history of America’s indigenous people—a history based on the accounts of the winners, how they have helped or hurt us, is just what has been so key in distracting us from the true history of native peoples and how we have helped or hurt them.

Up to 145 million and as few as 8 million (the number is debated) Indians lived in the U.S. in 1492, but in 1900 the number had reached its low point, at less than 250, 000. According to Ward Churchill the reduction of the American Indian population represents a “vast genocide…the most sustained on record.”

At most, 3 percent of the original population remained. The American Indians, contrary to what our school history books may teach (or not teach) us, did not disappear slowly. The series of events set in motion long ago demonstrate that American Indians were removed very deliberately, very carefully, and these events created lasting impacts on the few remaining American Indians today.

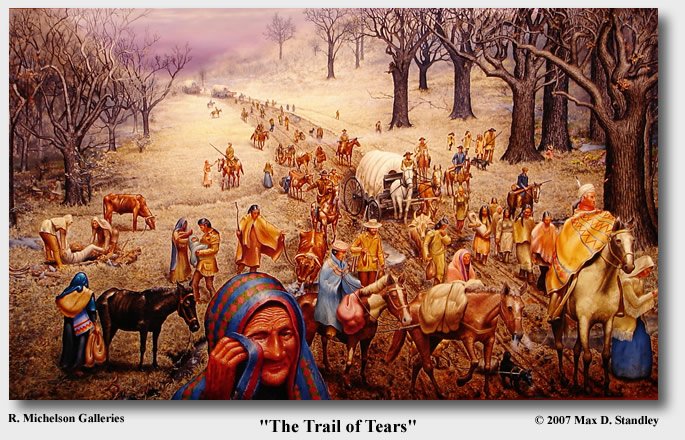

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act moved Indians west of the Mississippi in exchange for their homelands. The Trail of Tears, the forced relocation of over 16,000 Cherokee, resulted in over 6,000 deaths as well. In “God, Greed, and Genocide: The Holocaust Through the Centuries,” Arthur Grenke quotes Chalk and Jonassohn with regards to the Cherokee Trail of Tears that “an act like the Cherokee deportation would almost certainly be considered an act of genocide today.” The Indian Removal Act forcibly deported tens of thousands of American Indians from their homes into the west. However, the 1862 Homestead Act unleashed 15,000 white settlers into these very lands west of the Mississippi by the end of the Civil War in 1865. In 1871, The Indian Appropriation Act no longer viewed any of the Indians as independent nations, and made all Indians wards of the federal government. In addition, the military issued orders forbidding western Indians from leaving reservations. By 1900, after the Indian Removal, the responding American Indian wars, and several massacres, notably including Wounded Knee, the American Indian population, without land, without rights, without sovereignty dwindled to its lowest point. And though they have recovered in numbers, they have been failed in other ways. The statistics from today demonstrate the lasting impact of actions taken 200 years ago:

- The average Native American household income is $33,300, while the national average is $46,200. According to the 2000 Census, Indians living in Indian Country have incomes less than half the national average

- Alcoholism mortality rates are 514 percent higher than the general population.

- Suicide rates are more than double, and Native teens experience the highest rate of suicide of any population group in the United States.

- Diabetes incidence is 177 percent higher, with the highest rate of type 2 diabetes of any specific population in the U.S.

- Tuberculosis incidence is 500 percent higher.

- The national graduation rate for American Indian high school students was 49.3 percent for the 2003-4 school year, compared with 76.2 percent for white students. Just 13.3 percent of Native Americans have undergraduate degrees, versus 24.4 percent of the general population.

- Violence, including intentional injuries, homicide and suicide account for 75% of deaths for AI/AN youth age 12-20.

- AI/ANs attain the lowest level of education of any racial or ethnic group in the United States. Graduation rates for AI/AN high school students hover around 50% nationwide, as compared to over 75% for white students

In the war for land between the American Indians and the settlers who sailed into their harbors, only takes one glance at the statistics, and one glance around our campuses and cities to know who won.

To call the U.S. government’s systematic destruction of the indigenous people who lived on and owned the land before our arrival has been often called genocide. According to Aaron Huey, we are in the last chapter of this genocide: “The last chapter in any successful genocide is the one in which the oppressor can remove their hands and say, ‘My God, what are these people doing to themselves? They’re killing each other. They’re killing themselves while we watch them die.’ This is how we came to own these United States. This is the legacy of manifest destiny.”

How we came to own these United States, how we came to live in our suburban neighborhoods on stolen land, how we came to study at this university has a come at a cost. As you read this article, on your iPhone or laptop, waiting for class on this enormous and beautiful campus, think for a moment about the cost of those things, the cost of where you are today: a cost far higher and far more sinister than what your receipts might say.