By: Eli Scott

In 2011, the total trade volume between North Korea and China was $5.36 billion, but some researchers contest that one of North Korea’s main exports to China–brides–aren’t included in this figure. Such a quirk in the two countries’ trade balance is a result of the lasting effects of China’s former one-child policy. The one-child policy was eased in late 2013, but problems related to this state-mandated population control measure still linger in China and will haunt the nation far into the future.

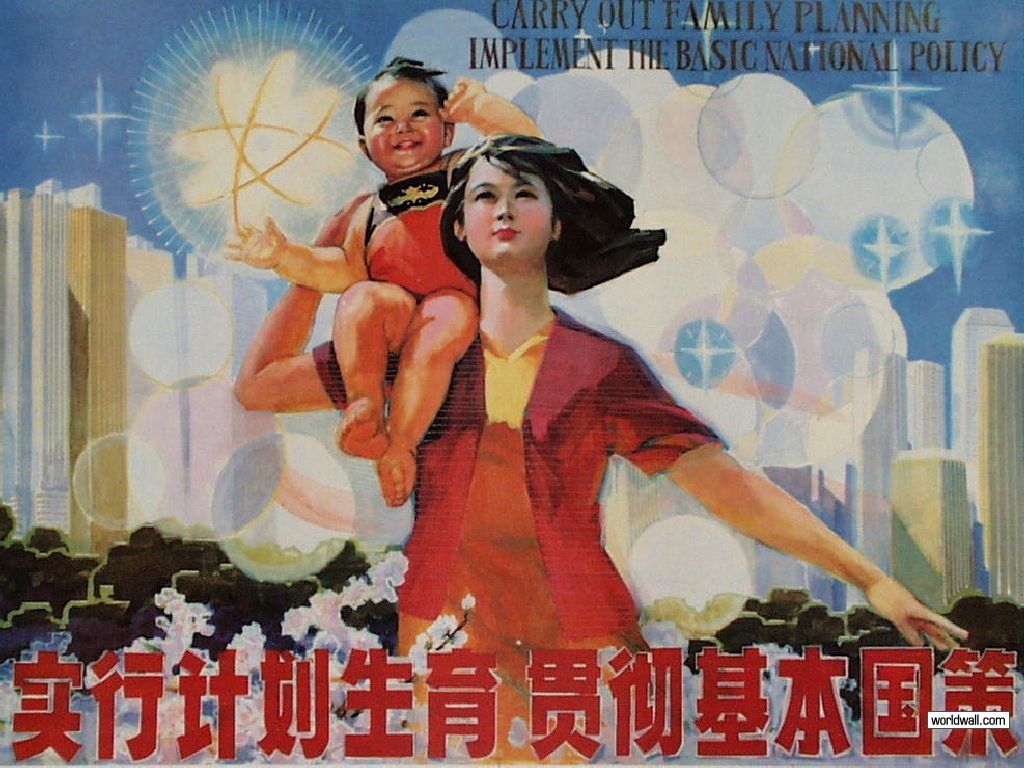

At the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the country contained 542 million people. By 1979, the population had skyrocketed to 975 million. To combat overpopulation, Mao Zedong instituted the one-child policy. While the policy prevented the births of more than 400 million children and purportedly hurled the country into modernization, it has caused a number of controversies and demographic oddities. The effects of the one-child policy are as far-reaching as the possible economic stagnation of the export powerhouse and disturbing as the resultant spike in sex trafficking.

Because of the inherent cultural preference for males due to their unique ability to pass on the family name in China, medical advancements such as ultrasound have fostered pre-birth gender bias, and this had led to an increase in the abortion of female fetuses. Although female infanticide is relatively uncommon today, rural Chinese couples have still found ways to subvert the one-child policy in order to ensure that they have a male child. Starvation, neglect, and abandonment of female babies has become more common since the advent of the one-child policy, and orphanage populations in China are predominantly female. This devaluation of women has been harmful to civil equality in China, and male surpluses may also have security impacts such as potentially increasing civil unrest and fostering a foreign policy based on aggression.

Sex ration at birth (SRB) is naturally determined to be between 103 to 107 males born for every 100 females. This natural proclivity toward male children is an evolutionary trend due to the fact that males are more vulnerable to diseases and sex-linked genetic mutations and are more likely to engage in risky, life-threatening activities. Abnormally above average, China’s current SRB stands at 118 male babies for every 100 female babies, and the SRB in rural areas can reach as high as 130. As a result, the Chinese population currently has 32 million more boys under the age of 20 than girls.

Over the next two decades, it is expected that between 12 to 15 percent of young adult men will be without marriage prospects. These wife-less men in China, called “bare branches,” pose a domestic threat as well as a threat to regional Asian relations.

Forty-eight percent of “bare branches” experience discrimination, and these men face above average rates of stress, alcoholism, suicidal thoughts, depression, and aggression. More tangibly, “every 1 percent increase in the sex ratio results in a 6 percent increase in the rates of [violence] and property crime.” As income inequality rises in China, increasing numbers of impoverished and less educated men, men already predisposed toward higher rates of violence and crime, are being left unmarried. Chinese policy makers should be wary of crafting such an unstable environment; the Nien Rebellion, which lasted from 1851 to 1868, serves as a historical example showing the social unrest that can result from an abnormally skewed sex ratio, particularly from one that includes 129 males per every 100 females.

Another issue of concern is the burgeoning sex trafficking market in Southeast and East Asia. Unmarried men also solicit sex twice as often as married men do. Women from the nearby countries of Vietnam, Laos, Singapore, Mongolia, and North Korea are commonly trafficked into the country. The U.S. State Department has proclaimed that China is one of the worst countries at combating sex trafficking.

In order to quell the woes caused by the one-child policy, China has eased its policy. Couples can now have two children if either parent is a single child; this is an expansion of the former policy, under which a couple could have two children only if neither spouse had siblings. This easing is intended to foster economic growth, but despite the new policy, China seems to have nearly hit its peak in terms of economic and population growth. Regardless, the one-child policy has become normalized to the point that Zheng Zhenzhen, a professor at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics, has claimed that less than 2 percent of parents cite the one-child policy as their reason for having only one child. These parents cited the high cost of housing and childcare as the main reasons. Additionally, increasing urbanization, the expansion of career and education opportunities for women, and changing attitudes and lifestyles may impede a population bulge due to the easing of the policy. In fact, Dr. Therese Hesketh, a professor at Institute for Global Health at University College London, has predicted a only a minuscule population increase of about one million in the next year as a direct result of the new policy.

The furthering of the demographic skew has forced China into a hyper-paced aging process, and, in light of its nascent pension plan, economic stagnation may occur due to a decrease in the work force. Currently, China is benefiting from the demographic dividend, which is “a short-term productive advantage due to a large labor force relative to small numbers of dependent young and old.” However, the country’s advantage is coming to an end. China’s current potential support ratio, the number of working-age persons to retirees, is about eight workers per retiree, much higher than that of Western European countries and other developed countries. But rapid aging–the median age has nearly doubled from 19 to 35 in the last 40 years–is bound to drive the worker per retiree ratio down soon enough. Chinese scholars estimate that the relaxation of the policy will increase the fertility rate from 1.6 to 1.8, but that still means that the population would peak around 2030; accordingly, by 2050, the potential support ratio would plummet to 2.6 working age persons to retirees. Such a decrease in the workforce would halt the Chinese economy assuredly.

Although the easing of the one-child policy is nominally a step in the right direction for the Chinese government, changing attitudes may prove this policy to be ineffective in fostering sufficient population growth. The lasting effects of the one-child policy, including the vast male surplus, will present many challenges in China’s future, especially if internal conflict caused by “bare branches undermines its rising international power. Nonetheless, population control policy may prove to be irrelevant in China’s course on the international stage, and its demography may predispose an early decline in population and economic growth if its aging population is able to strip resources away from a shrinking workforce.