By: William Robinson

China is the world’s largest owner of the U.S. government’s debt, holding $1.273 trillion worth of U.S. Treasury securities as of February 2014. As a result, many pundits, policymakers, and analysts fear that these holdings give China leverage over U.S. policymaking, as this 2010 commercial by Citizens Against Government Waste hyperbolically suggests. Others forecast a doomsday scenario in which China dumps its holdings back into the world market, crushing the value of the dollar. Contrary to these claims, however, current research suggests that China benefits from its U.S. debt ownership and has much to lose by dumping its holdings.

The Debt Market

The U.S. government consistently relies on deficit spending—spending more money than the government brings in through taxes—in order to provide a high number of government services without a heavy tax burden. To account for this deficit, the government sells stocks and bonds (securities) to the public and in international capital markets. The government can immediately spend the money it acquires through the sale of bonds, but the bonds must be paid back with interest out of future national income.

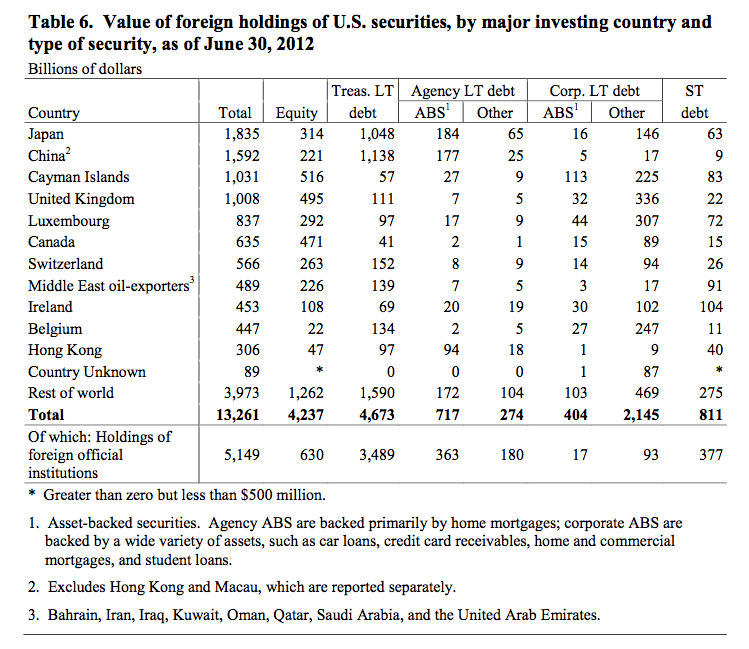

Historically, the American public held the vast majority of governmental security holdings. However, in recent years the U.S. government increasingly relies on foreign investors. In fact, foreign investors held $13.261 trillion dollars (75 percent of our current national debt) in U.S. securities in 2012, as this table from the Treasury Department shows.

Why China Wants American Debt

China’s economy has grown drastically since the early 2000s. The engine for this growth is a methodology called export-oriented growth. As the name implies, export-oriented growth is a government-led focus on exports. Governments that apply this method encourage the production of goods that are in demand internationally, acquire access to global markets, and export at a high volume. If the strategy is effective, high employment will follow high productivity, and the nation will export more than it imports, resulting in significant capital accumulation.

China’s export-oriented growth has been wildly successful, but its means of accomplishing this growth are controversial. The most contentious of these means is China’s undervaluing of its currency, the Renminbi (RMB). Getting “tough” on China and the threat of a “trade war” became hot topics during several 2012 presidential campaign debates. However, China’s policy of undervaluing the RMB is actually the reason China owns so much U.S. debt.

Because China is export-oriented, its government wants products “Made in China” to be cheaper than international competitors’ products. China has succeeded in doing this by avoiding currency appreciation, the increase in value of the RMB relative to other currencies. For example, one U.S. dollar is currently worth 6.23 RMB; if the RMB appreciates relative to the U.S. dollar and 6.23 RMB becomes worth two U.S. dollars, the purchasing power of the U.S. in China would be cut in half. Chinese products would cost twice as much for U.S. consumers even though China did not change any prices. As a result, the United States would import a smaller quantity of Chinese goods. A decrease in the quantity of exports is the nightmare scenario for China’s government, which must keep hundreds of millions of workers employed. Therefore, China maintains a low currency value in order to keep its exports the cheapest in the market.

But how exactly does China go about keeping its currency from appreciating? This is where American debt comes into play. Purchasing U.S. securities gives China’s central bank a large reserve of dollars to meet their desired RMB-dollar ratio. The Central Bank is the only bank in China that can legally keep its U.S. dollars (all others give their U.S. dollars to the Central Bank in exchange for RMB), and the Central Bank then prints enough RMB to retain the same ratio between the currencies. U.S. securities are a safe investment because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. America is also the only nation with a large enough debt market to absorb a significant amount of the wealth generated by China’s trade surpluses.

Thus, Chinese acquisition of American debt enables the United States to do what it has traditionally done—consume more than it produces—and helps China do what it has traditionally done—produce more than it consumes.

Is There a Threat?

Most experts and analysts have agreed that there is not a significant threat of China exerting influence on U.S. policymaking by using debt ownership as leverage. If China were to suddenly sell its reserve of U.S. securities, there would likely be a market-wide panic, causing other nations to sell their reserves of U.S. securities. The market would thus be flooded with a supply of U.S. securities, and the value of the dollar would plummet. This is the doomsday that some envision. However, if the dollar were to depreciate drastically, so would U.S. purchasing power abroad, meaning the United States could not afford to continue importing a high volume of Chinese goods. Furthermore, without an alternate debt market in which to bury China’s wealth, the RMB would appreciate. Even worse, the devastation inflicted on the U.S. economy would be disastrous for the world economy as well, hurting other nations’ abilities to afford Chinese goods. China would be left with an abundance of goods that no one could afford to buy, which in turn would cause high unemployment. In sum, China stands to lose a lot if it were to exploit its only supposed “bargaining chip” over U.S. policymaking.

America’s reliance on China is indicative of a larger problem, however. Continued deficit spending, reliance on foreign investments to cover debts, and printing large quantities of currency are all unsustainable policies. China recognizes the risks associated with these.

“Chinese officials have expressed concerns that actions by the Federal Reserve to boost U.S. monetary supply will undermine the value of China’s holdings of U.S. dollar assets, either by causing the dollar to depreciate against other major currencies or by significantly increasing U.S. inflation,” wrote Wayne Morrison in a Congressional Research Center report.

Additionally, America’s long-term sovereign credit rating by Standard and Poor dropped from AAA (outstanding) to AA+ (excellent) in August 2011. Thus, China has reason to question the safety of its investments in U.S. securities.

China has started a gradual move towards diversifying its investments, but in the short-term, it has few alternatives to the massive U.S. capital market. In the long-term, diversification may strengthen China’s export-oriented strategy by better ensuring the security of its investments. Nonetheless in the near future, China needs the U.S. in order to keep producing, and the United States needs China in order to keep consuming. This is the symbiotic relationship of the world’s two largest economies.