Coffeeshops have always been a place of political discussions, intellectual debates, and social inquiry. The pensive act of sipping coffee surrounded by comfy seating and individuals deep in thought or conversation make the coffee shop the perfect institution for sparking social change. The Arab Spring took off in Egypt and Tunisia partly thanks to Internet cafes, coffeehouses where young people could discuss political grievances and plot revolution. Across time and place, coffee shops have always served as a forum to challenge the status quo.

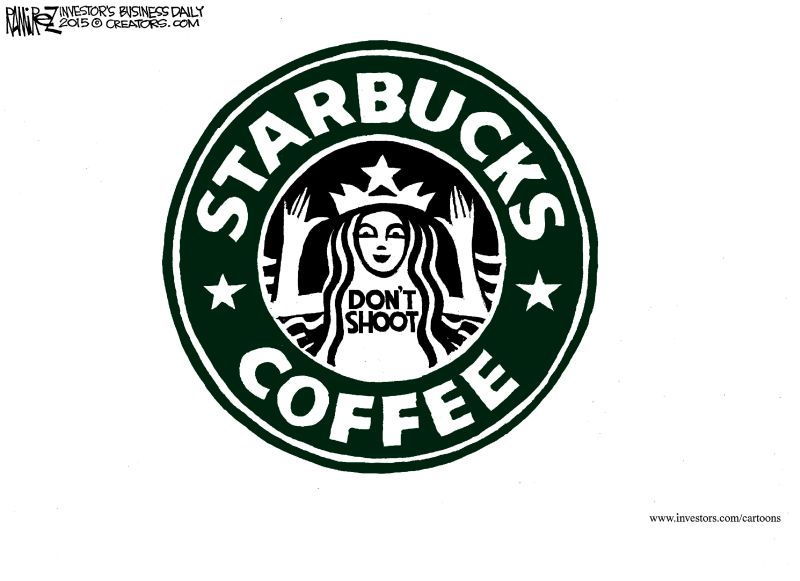

This is exactly what Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz had in mind when he introduced the #racetogether campaign. The Starbucks website describes their goal to start coffee shop conversations about race across the country:

“As racially-charged tragedies unfolded in communities across the country, the chairman and CEO of Starbucks didn’t remain a silent bystander. Howard Schultz voiced his concerns with partners (employees) in the company’s Seattle headquarters and started a discussion about race in America. Despite raw emotion around racial unrest from Ferguson, Missouri to New York City to Oakland, “we at Starbucks should be willing to talk about these issues in America,” Schultz said. “Not to point fingers or to place blame, and not because we have answers, but because staying silent is not who we are.”

Despite the seemingly well-intentioned nature of the campaign, it met immediate criticism. Opinions ranged from bemusement to outrage. Twitter was flooded with playful quips, most in agreement that the policy was a farce.

"You've opened my mind. Write 'Martin Luther King' on my latte cup."

CLOSE UP: Latte with "Marda Lou Thinking" on it. #RaceTogether— Patton Oswalt (@pattonoswalt) March 20, 2015

Many critics, however, found the trite slogan, #racetogether, more than just a ridiculous and inadequate attempt to solve our country’s entrenched racial divides. At Fusion magazine, Danielle Henderson wrote, “It’s the height of liberal American idealism and a staggering act of hubris to think we can solve our systemic addiction to racism over a Frappucino.” She goes on to say, “This seems like a clear case of the bourgeoisie pushing the proletariat to do the heavy lifting while their own lives carry on unchanged.”

Henderson argues that Starbucks has put the onus of starting these “race conversations” on the baristas. The same people who deal with you deciding that you want an iced skinny soy caramel macchiato instead of a venti caramel flan Frappuccino now also have to guide the American public in racial soul searching. Furthermore, the Starbucks executive board is overwhelmingly white, while 40 percent of baristas, or “partners” as they are referred to corporately, are minorities. This kind of corporate-sponsored grassroots initiative feels not only inauthentic, but also slightly condescending. Imagine, the white CEO of Starbucks has finally told us how to fix racism! It certainly smacks of the White Savior Complex. What’s more, they’re trying to make money at the same time.

An Economist article explains America’s negative gut reaction: “Americans’ instinctive disdain for Race Together seems to be rooted in the sense that Starbucks was appropriating a serious social issue for its own economic gain.” Yet, Starbucks is by no means the only company to commodify social action. Some have even been successful. The key is authenticity. The article cites TOMS and Dove’s real beauty campaign as winners. “Indeed, brands tend to be rewarded when they align themselves with feel-good causes. Consumers are often grateful for a chance to feel self-righteous without having to do anything more than make a purchase. But for this to fly, the branding effort needs to seem authentic and not merely cynical or self-serving.”

This explains why the #racetogether campaign seems so ridiculous and presumptive. What business does Starbucks, the very bastion of whiteness, have with fixing race relations in America? Racial demographics of Starbucks customers are hard to find, yet when talking about the company’s public image, the stereotype matters just as much. Starbucks and white girl are practically synonymous in popular culture. It may appear as though Starbucks is appropriating racial discourse, not in an effort to actually confront racism, but to market off of white guilt.

But let us return to the idea that consumers like to feel good about what they buy. Was it always like this? Certainly, consumers in mid-twentieth century didn’t care whether their white bread was ethically sourced or if their shampoo brand “gave back.” This is not to say that Americans were less morally-minded than today. Individuals still gave to charities and philanthropic causes, but there was a clear delineation between the economic realm, which dealt exclusively with commodities, and civil society, which worked to better the world. Arguably, we have made great strides in improving business practices, particularly in agriculture. But most companies do not do this out of goodwill. What kind of business plan would that be? Companies shift to a more ethical business model when there is market pressure to do so. In other words, morality has become another commodity that we can buy and sell, an added feature to goods to make them more attractive by absolving our consumerist guilt.

Slavoj Zizek, an anti-capitalist philosopher from Slovenia, discusses this idea in his film “The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology.” (It’s on Netflix!) With a thick accent and a robust, cynical sense of humor, he is a fascinating character. In the clip below, he discusses how Starbucks promotes its ecologically responsible ethos as part of their product, allowing us to propagate destructive consumerist structures without the guilt formerly associated with it.

“Now, I admire the ingenuity of this solution. In the old days of pure, simple consumerism, you bought a product and then you felt bad. ‘Oh, I am just a consumerist while people are starving in Africa….’ So the idea was that you had to do something to counteract your destructive consumerism. What Starbucks enables you to do is to be a consumerist without any bad conscience, because the price for the counter-meausure, for fighting consumerism, is already included in the price of the commodity…. It is, I think, the ultimate form of consumerism.”

Evidence also shows that fair trade policies like those that Starbucks champions are surprisingly ineffective. Well intentioned, they seek to give farmers “fair prices” to help lift them out of poverty and make up for decades of imperialist manipulation of their primary resources. Yet no data shows any alleviation of poverty where these fair trade policies are enacted. They persist, however, because Starbucks can advertise all the good they’re doing for the starving coffee farmers of Africa, Latin America, etc…

Zizek asserts that this kind of commodification of morality serves to protect capitalist structures by co-opting the very guilt that should lead to their dismantlement. In the same way, Starbucks appears to be capitalizing on the white guilt rampant among its customers by including racial dialogue in every Pumpkin Spice Latte. Look, you’re destroying racism in America with every sip.

Was marketing off of American’s sense of racial injustice the conscious intention of the #racetogether campaign? Perhaps not. Yet, Zizek’s analysis of American consumerist culture is interesting nonetheless. His perspective allows us to step back from the normalcy assigned to capitalism’s mechanisms and analyze how our thoughts and behaviors are influenced by consumption. Whether or not the socially conscious trend in American business actually does much to combat the ills of our society is up for debate. However, as consumers and as members of society, it is our duty to examine what we consume and how it influences what we think and believe. So, when your barista asks you what you think of white privilege as he hands you your latte, actually think about it. But also consider why Starbucks is asking you that question in the first place.

Or, just do what the guy in front of you did: awkwardly mumble “sorry,” and walk away because you’re in Starbucks and…. what?

– By Bailey Palmer