By: Hammad Khalid

The new face of cancer is not cancer of the lung, breast, colon, or prostate. Instead, thyroid cancer is now the most common cancer in South Korea, after a fifteen-fold increase in incidence over the past two decades. Although thyroid cancer rates have more than doubled since 1994 in the United States, and similar upward trends can be found in Europe, nowhere in the world has the rate of any cancer grown faster than that of thyroid cancer in South Korea.

Such a sharp rise in incidence typically indicates a real increase in disease prevalence, which can be directly correlated to increased mortality rates from the disease. These significant increases are usually rationalized via biological explanations, such as a new infectious agent or novel environmental exposure to pathogens. In this case, experts have agreed that South Korea’s thyroid cancer epidemic is instead a direct result of increased cancer screening.

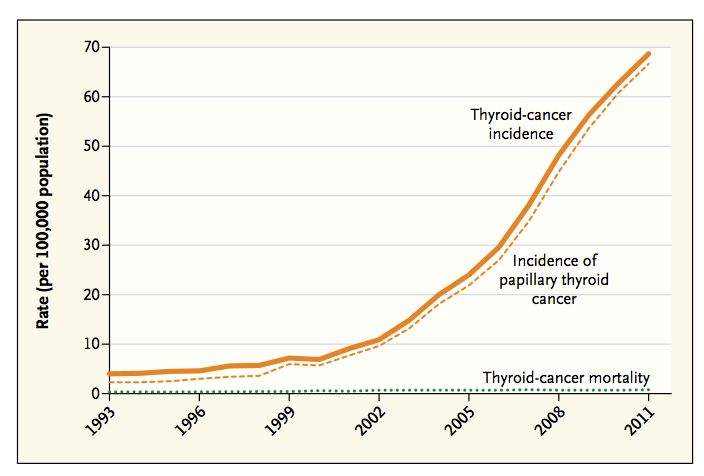

In 1999, the South Korean government initiated an ambitious, national cancer-screening program for breast, cervical, colon, stomach, and liver cancers among others, often free of charge. Physicians and hospitals would often include ultrasound scans for thyroid cancer for a small additional fee ranging from $30 – $50. Shortly thereafter, thyroid cancer diagnoses began to skyrocket. Although over 40,000 South Koreans were diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2011, less than 400 people die from thyroid cancer every year.

Even though an increasing number of cases of thyroid cancer is being found every year, the death rate remains stable. If earlier detection truly were saving more lives, the death rate should have decreased. That the death rate is still constant is telling of the fact that many of the new cancers being diagnosed are not fatal. This leads to a phenomenon known as medical overdiagnosis, in which diseases such as cancers that grow very slowly or not at all are found and treated unnecessarily because of preliminary screening and incidental findings.

Although the issue of medical overdiagnosis is most prevalent with thyroid and prostate cancer, it also exists with lung, breast, skin, and kidney cancers to a lesser extent. Overdiagnosis is a difficult problem to overcome because pathologists cannot tell which small tumors are likely to be dangerous, and most people do not want to take chances when they find out they have cancer.

However, South Korea’s experience with thyroid cancer overdiagnosis should serve as a cautionary tale for the United States and the rest of the world. While early screening does make sense for some, such as those with a family history of the cancer, other people interested in early detection may actually benefit from ignoring microscopic cancers. For instance, many of the thyroid cancers found in South Korea were papillary thyroid cancers less than a centimeter in size. These papillary thyroid cancers are generally indolent – as many as a third of people are found to have tiny, undetected thyroid cancers on autopsy. A vast majority of these cancers will not produce symptoms during a person’s lifetime.

Virtually everyone diagnosed with thyroid cancer undergoes some form of treatment. Despite the fact that guidelines recommend against surgery for tumors less than 0.5 centimeters in diameter, a quarter of surgical patients have tumors that fall into this category. Most patients who undergo some form of surgery for thyroid cancer have long-term implications. Many must receive lifelong thyroid-replacement therapy, and a few have complications such as vocal-cord paralysis. Then there is always the chance of less common, life-threatening surgical complications, such as blood clots in the lungs, heart attacks, and strokes. In approximately two out of every 1,000 thyroid cancer operations, the patient dies from surgical complications.

While most people have been taught that early screening and cancer detection is always a good thing, South Korea’s experience tells a starker story of the negative implications of medical overdiagnosis. Spreading awareness that not all cancer is deadly and finding cancer early can actually do more harm than good in some cases is not an easy task because early cancer detection is so intuitively appealing at first. Nonetheless, this setback should not take away from the significance of the task at hand. Over the past two decades, multiple nations have had substantial increases in thyroid cancer without a simultaneous increase in mortality, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer. France, Italy, Israel, China, Canada, and the United States are among the countries that have seen more than a twofold increase in thyroid-cancer incidence over the past twenty years. The South Korean experience indicates that this could just be the tip of the thyroid-cancer iceberg – if these aforementioned countries don’t take notice quickly and discourage early thyroid-cancer detection, overdiagnosis, and subsequent overtreatment – they might face their own thyroid cancer “epidemic” like South Korea.