This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 edition of the Georgia Political Review.

In 1999, college student Ryan Gravel’s master’s thesis was an ambitious proposal to restructure and reconnect Atlanta by drawing a green circlet of parks and rail transit around the perimeter of downtown Atlanta. Fast-forward 17 years, and this idea is now commonly known as the Atlanta BeltLine (ABL), which began development upon its approval by the Atlanta City Council in 2005. Today many parts of the ABL have come to life. The northeastern loop of the ABL has especially transformed its surrounding areas, and impressive housing and business developments continue to spring up around the pathway. However, not all of the BeltLine is created equally. The western and southern portions of the BeltLine are largely unfinished and disconnected, and these are the portions of the ABL that pass through the most poverty-stricken areas in metropolitan Atlanta. The planned ABL rail line has not even begun construction, with some sources saying it could be cut from the ABL altogether. With the project expected to be complete by 2030, it is too early to say what the finished BeltLine will do to Atlanta, but the initial developments of the ABL have raised questions.

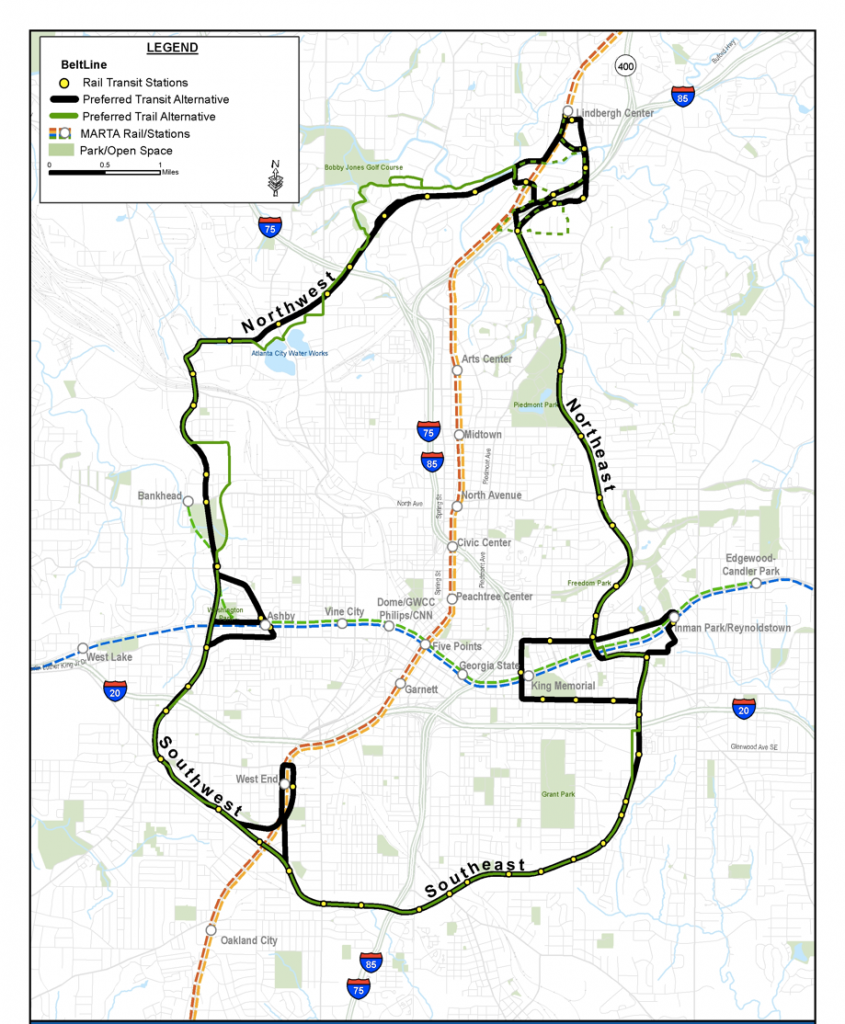

Atlanta began as a city defined by its comprehensive railroad system, and the ABL aims to revitalize the city’s old railroad infrastructure by following a 19th century railroad path around downtown Atlanta. In short, the BeltLine is a planned 22-mile pathway that connects 45 Atlanta neighborhoods and constructs a light rail system adjacent to the path. It further creates a greenway of 1,200 park acres interconnected by multi-use transit trails. The project’s estimated cost is 2.8 billion, and it has garnered 350 million dollars from private donations and property taxes.

Procuring funding for the ABL has been sluggish at best. In one instance, the ABL’s funding model introduced a measure that took property taxes, which were previously used to fund Atlanta Public Schools (APS), to pay for its construction costs. The BeltLine’s plan was to spend APS’s tax dollars now, and gradually pay them back after the BeltLine secured more funding. Although the ABL’s plan to gradually pay back the APS for their borrowed tax dollars seemed fair, they missed one of their payments. Adding to the funding struggle, the Georgia General Assembly voted down a 2011 bill increasing the Georgia sales tax by one penny that was meant to fund the ABL. Even in 2016, the BeltLine project has progressed gradually and concerns over its full completion have arisen.

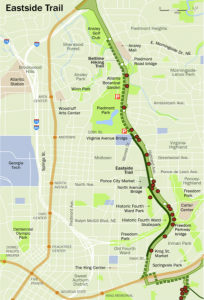

Business and housing developments, artwork, and general liveliness have virtually transformed Atlanta neighborhoods around the northeast ABL loop (Figure 2), especially Old Fourth Ward neighborhood, and these changes are byproducts of the ABL’s proximity to the community. Today, the historic home and neighborhood of Martin Luther King Jr. sits just a couple blocks from Krog Street Market, a marketplace for gourmet eats and local beer. Old Fourth Ward, the historic neighborhood where the Civil Rights Movement began, is being renovated and gentrified as a result of developments around the BeltLine, similar to the gentrification of Inman Park in the early 2000s. Although the ABL has brought much economic stimulation to Old Fourth Ward, it has simultaneously displaced many low-income residents that have resided in this historic neighborhood for decades. In fact, median home values in parts of Old Fourth Ward have increased by 119% since 2000, and Atlanta had the nation’s 5th fastest gentrification rate in 2013.

After spending time on the BeltLine, it becomes clear that the ABL is incomplete in many areas. Living near the BeltLine, I have used the northeast loop many times for jogging and leisure. The northeast pathway is full of life; thousands of people use the path daily, and the new Ponce City Market housing/business development conveniently connects with the ABL, attracting even more business and economic stimulation to the northeast ABL corridor. However, on my first visit to the BeltLine, I ran northwards on the northeast loop, and suddenly reached what seemed to be the end of the path. This is because the ABL is largely unfinished. In fact, the northeast loop is the lone-shining jewel in the necklace that is the ABL. Existing parks, trails, and green-spaces are located in segments on the BeltLine, but most are not yet connected by the ABL’s planned multi-use pathway. The vast majority of economic, urban, and cultural development has been around the northeast loop, with the west and south loops largely underdeveloped and disjointed.

Figure 3. In the images, the blue dotted lines represent parts of the ABL under construction. The red dots on the map are artwork locations on the ABL. (Beltline.org)

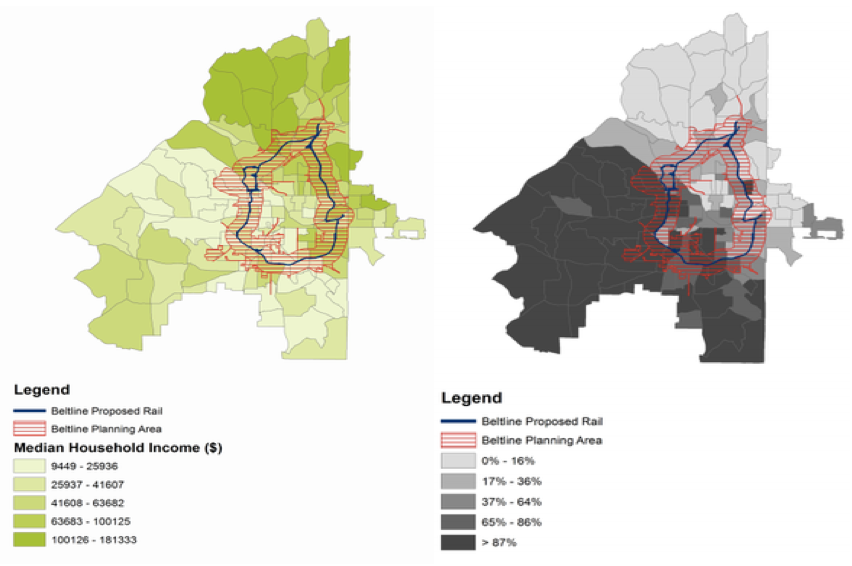

One of the concerns with the ABL project is that it will exacerbate the social, racial, and urban divisions that already characterize Atlanta. Figure 4 shows the de facto racial segregation in the metropolitan Atlanta area: predominantly lower-income African Americans reside in west and south Atlanta, while upper middle class white denizens are established in the eastern and northern rims of the city. Additionally, the median household income in west and south Atlanta is vastly lower than north and east Atlanta. Although the BeltLine passes through the western and southern portions of Atlanta, these portions are the most underdeveloped segments of the ABL (Figure 3). If the BeltLine aims to reinvigorate and connect Atlanta, it needs to distribute its resources equally across the path. Completing construction on the parts of the BeltLine that benefit higher income Atlantans and shortchanging the lower income, predominantly black populations is a mistake.

Although the BeltLine has been shown to mostly benefit upper middle class Atlantans, ABL has taken action to combat its tendency to gentrify communities. Byproducts of economic and urban development have reinvigorated downtown Atlanta, and the BeltLine has made promises to combat gentrification by allocating affordable housing for communities surrounding the BeltLine. In the proposed plan for the ABL, 15 percent of the Tax Allocation District will go to public housing, and the BeltLine project promises to erect 5,200 units of affordable housing throughout its surrounding communities. These are significant arrangements that would combat the BeltLine’s tendency to gentrify surrounding communities. Furthermore, the Beltline has provided local workers with thousands of construction jobs in the surrounding communities, acting as a jobs stimulus as well as inviting communities to take part in the ABL’s development. While it is easy to shortchange the BeltLine for the discrimination of its construction efforts, the ABL has begun to construct the west and south corridors, and its plans for 2016 boast of increased funding and equally dispersed efforts for lower and middle-income areas of the BeltLine.

While the BeltLine has only begun its initial steps to reconnect and restructure Atlanta, it has raised questions of its commitment to promoting both meaningful and equally dispersed change to Atlanta’s sharply divided socioeconomic and racial communities. Yet, the ABL is a just “a narrow strip of land,” and its slender path that encircles Atlanta should not be held accountable for remedying all of Atlanta’s current glitches. It is, as BeltLine creator Ryan Gravel says, what happens around the BeltLine that will determine the true outcome of the project. However, current BeltLine construction has benefitted mainly upper middle class Atlantans at the expense of lower income populations who have not yet seen the benefits of the BeltLine. If the BeltLine’s goal is to benefit and bring together Atlantans, it needs to be constructed and disseminated in a manner and punctuality that benefits the entire city and not just certain parts.