By Daniel Klein

On Dec. 6, 2022, Sen. Raphael Warnock quelled a challenge from former University of Georgia and NFL football star Herschel Walker in Georgia’s U.S. Senate runoff, after a neck-in-neck general election left no candidate above the victory threshold of 50%. While family scandals, controversial policy stances, and doubts about Walker’s character beleaguered his path to victory, polls frequently projected that Warnock would lose, with aggregate pollsters such as FiveThirtyEight predicting a one-point Walker win prior to the November general election. Yet, Warnock secured a nearly 3% margin of victory–a resounding victory for a Senate election in Georgia, where three out of the last four races have been decided by 2% or less. This begs the question of how Democrats held a Senate seat in a traditionally conservative state against a widely-recognized name in a year that favored Republicans amid national discontent with the Biden administration.

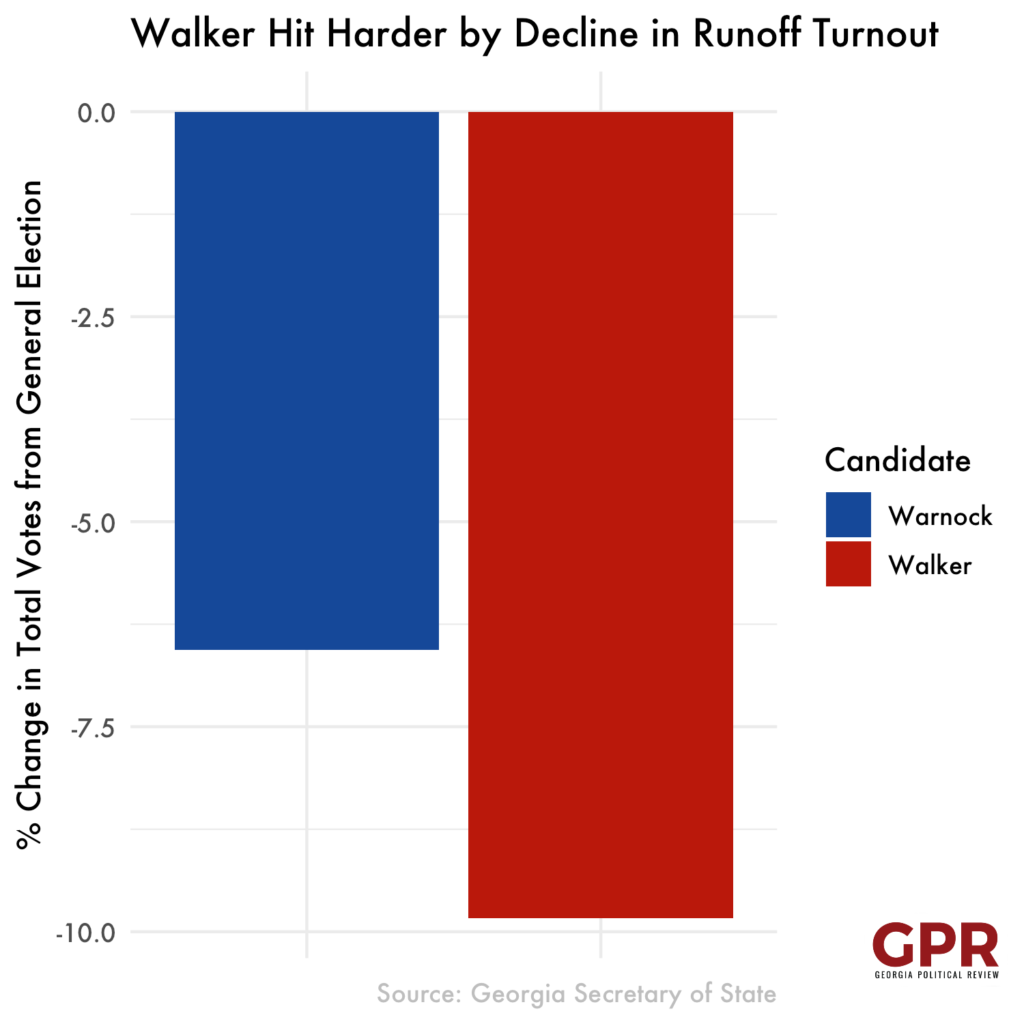

First, Georgia’s runoff election saw a significant decrease in turnout–but that decline in voter participation was not equally distributed between candidates. Turnout reductions are normal for runoff elections; for example, when two Senate races in Georgia also went to runoff in 2020, turnout decreased by 10%. That pattern held in the most recent election, where statewide turnout decreased from 56.9% in November to 50.5% in December. Warnock’s deflated number of votes matches the overall trend in a nearly flawless fashion, receiving 6.6% fewer votes. However, Walker’s vote count diminished greater than the overall trend, garnering 9.8% fewer votes than in the general election. This statistical disparity points to two trends that likely doomed a GOP win–Republican voters’ unenthusiastic attitude toward Walker, and Democrats’ motivation to reelect Warnock.

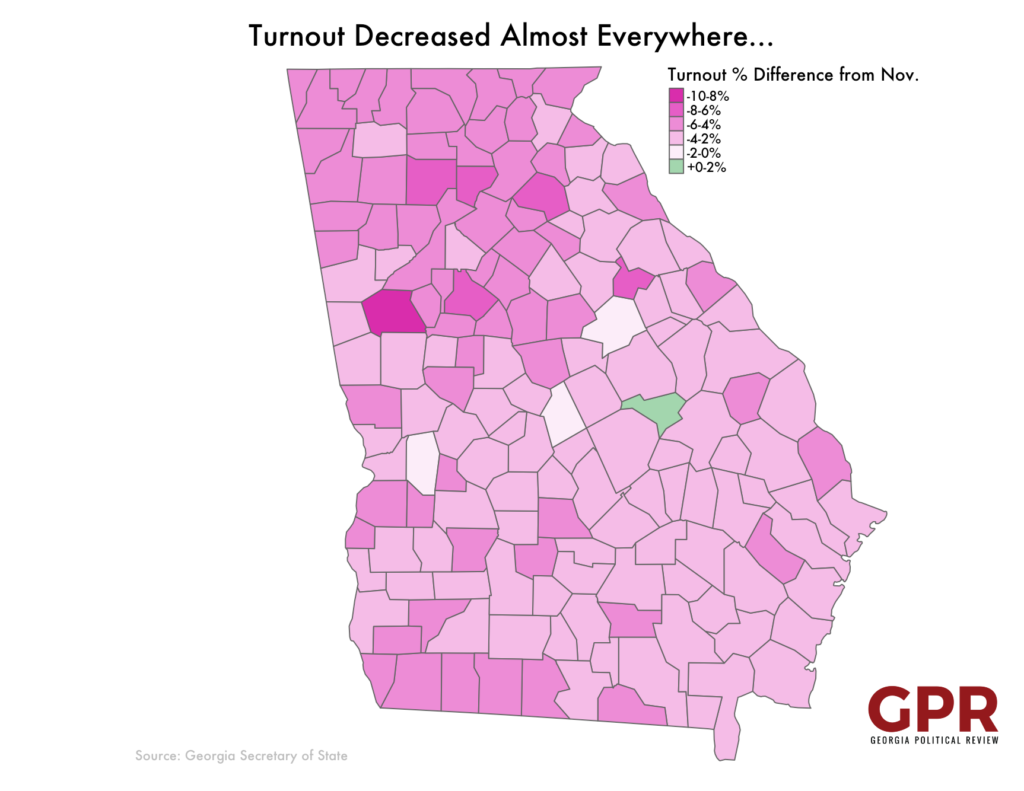

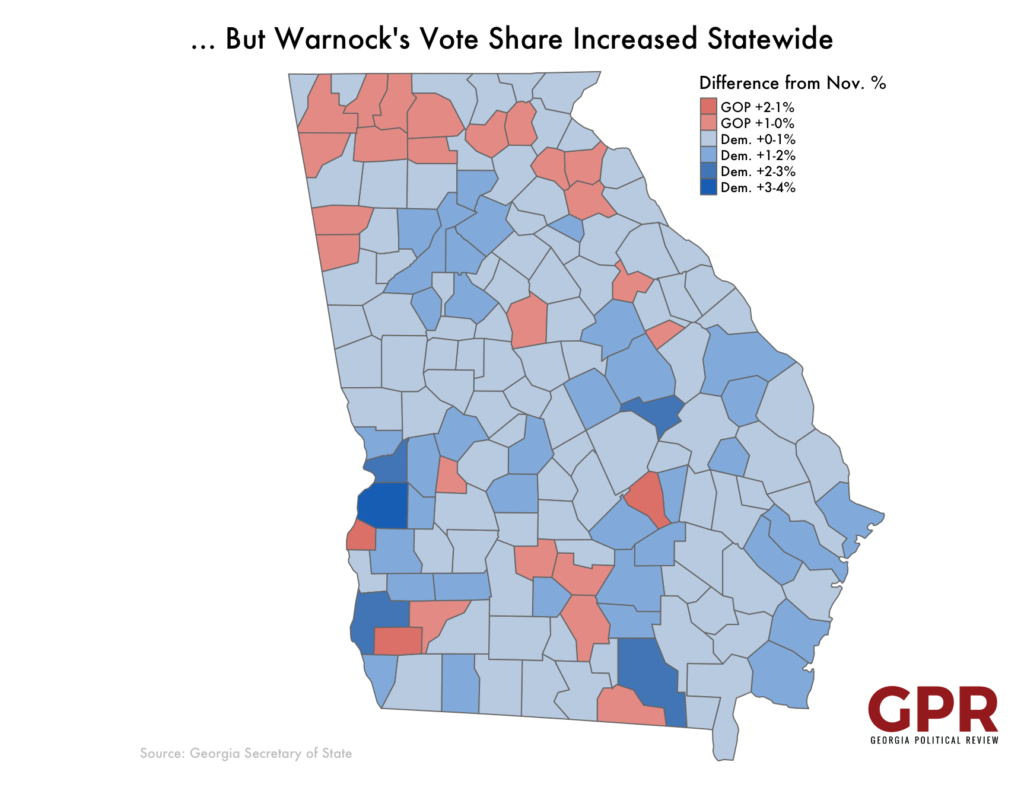

The severity of Walker’s dwindling popularity among voters is even more apparent when examining where turnout changed. Rural counties, the heartland of Republican support in Georgia, generally saw smaller decreases in voter turnout in the range of 2-4%. These reductions were smaller than the statewide average as well as urban and suburban Democratic strongholds–something that should have been a good sign for the GOP. Election pundits noted that to win, Walker would have to greatly shore up his rural margins in the runoff. However, across the state, even in these Republican strongholds, Warnock actually increased his share of votes, indicating that of the voters that turned out on Dec. 6, a greater proportion voted Democrat.

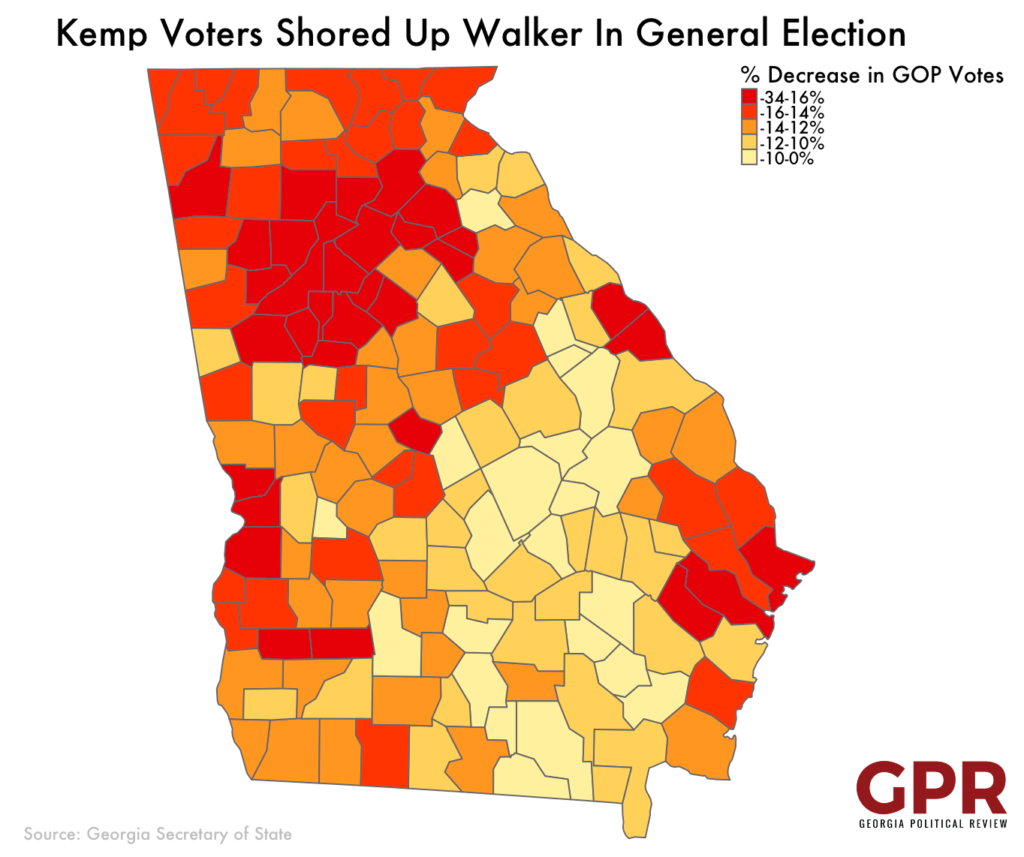

When comparing Republican Gov. Brian Kemp’s recent election results to Walker’s, low enthusiasm for Walker among Republicans becomes even more apparent. Despite the high stakes of the Senate race for a Republican party trying to claw back control from a 50-50 Senate, Walker received 200,000 fewer votes than Kemp on the day of the general election. This phenomenon cannot be entirely attributed to Kemp’s popularity with moderate Democrats or independents–exit polls indicate that moderates favored Stacey Abrams by 24%, while independents were split almost evenly 48% Abrams to 49% Kemp. In other words, Republican voters showed up to vote for Kemp but balked at voting for Walker. After Kemp was no longer on the ballot in December, Walker was left high and dry. Compared to the number of votes Kemp received in November, Walker’s support in the runoff plummeted, with heavily-populated counties such as Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, and Cobb seeing decreases in the range of 20-34%. Walker’s runoff tumble reveals that a substantial portion of his general election voter base was motivated to turn out with Kemp at the top of the ticket, but lacked enthusiasm about Walker’s candidacy.

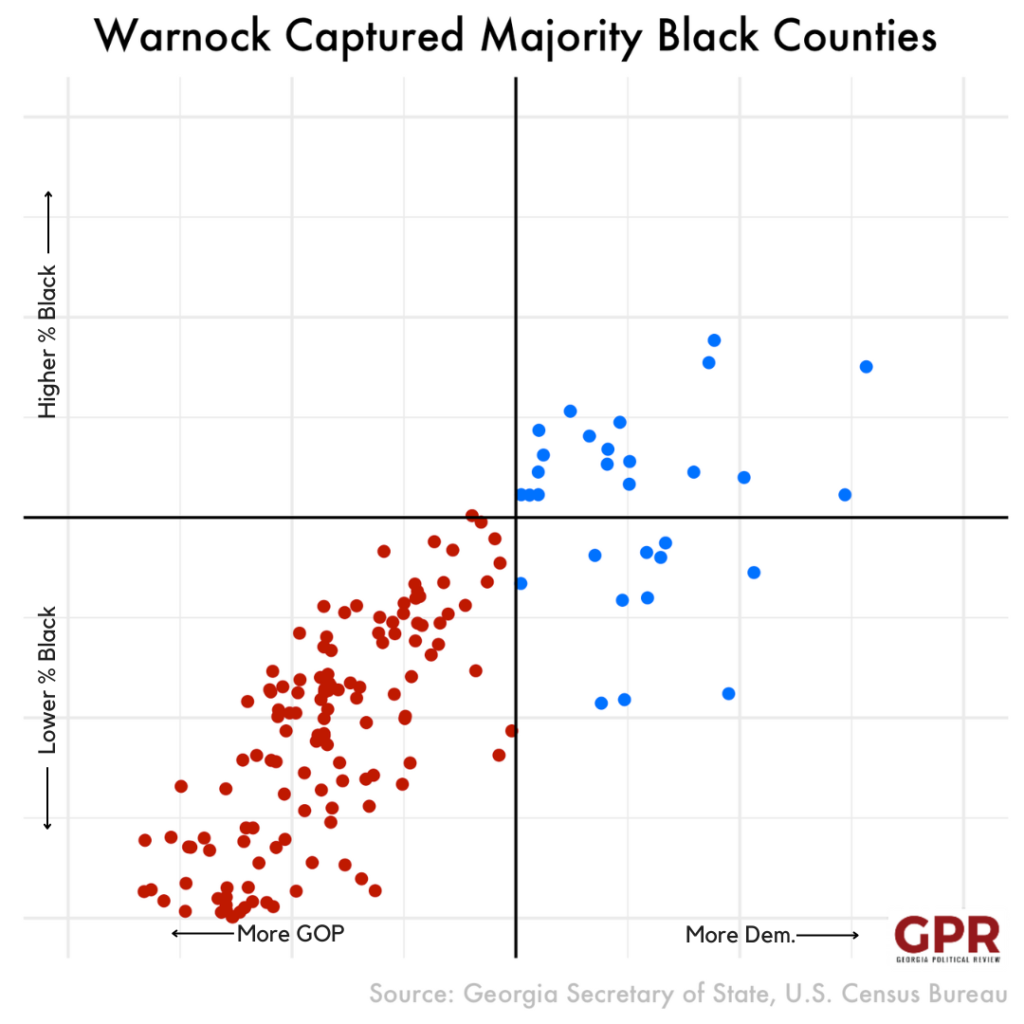

In an election between two Black candidates, there was speculation that the votes of Black Georgians would become more evenly spread between parties, with Walker capturing a far greater share of the demographic than past GOP candidates. Alas for Republicans, this racial reorientation did not occur. Walker only won only one majority-Black county (Early County) out of Georgia’s 20 and exit polls showed that Black voters broke for Warnock 90% to Walker’s 8%–almost the exact same margins as Warnock’s defeat of Kelly Loeffler in 2020. During his campaign, Walker frequently discussed issues of race and racism, or rather, his nonbelief in their existence in modern America, inquiring at a rally in May, “where is this racism thing coming from?” It is clear that Black voters did not feel drawn to Walker’s platform any more than previous Republicans, despite his race, proving that a candidate’s rhetoric and policies speak to a minority group far louder than the candidate’s own identity.

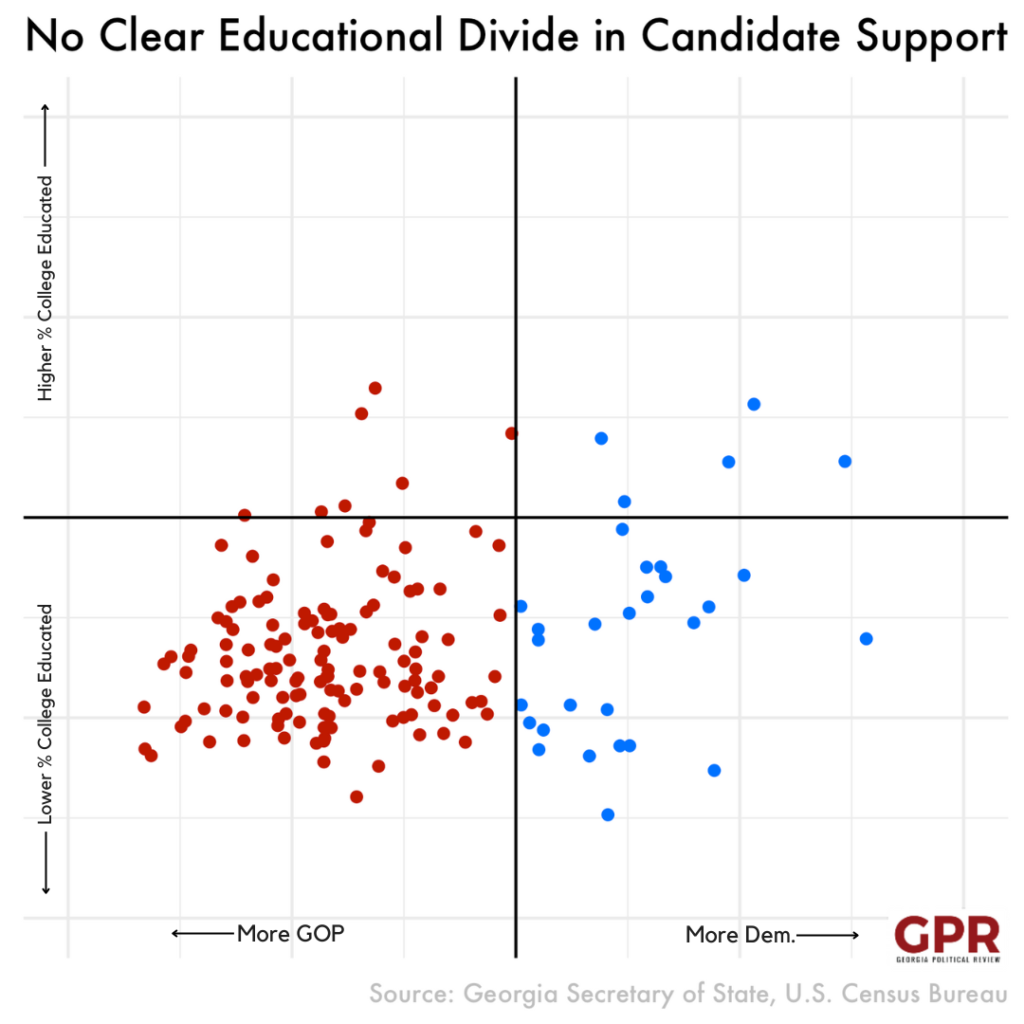

Educational polarization is an oft-discussed topic in recent years. This hypothesis posits that the Democrats have become the party of the college-educated, while Republicans have become champions of those with lower educational attainment. However, Georgia’s Senate runoff disputes this idea. Walker won seven counties with a majority of college-educated residents (who either attended college or received a bachelor’s degree or graduate degree) to Warnock’s five. Walker did win a far greater number of counties with low numbers of college-educated residents, but the divergence is not as distinct as one might expect. Exit polls confirm this trend: there was a near 50-50 split among voters who attended some college or earned a college degree. Only graduate degree-holders and those who never attended college broke heavily for one candidate. The lack of a strong alignment between political parties and educational status contradicts claims of strong educational polarization. Instead, it is clear that the demographic nature behind party affiliation cannot be boiled down to one characteristic like education, and what compels a citizen to vote for one party or the other is more complicated than a single variable like educational attainment.