By: Michael Ingram

In an Instagram video uploaded on Jan. 6 by Miss Venezuela 2004 Monica Speer, amber sunbeams cast shadows over the halcyon plains of Carabobo state, Venezuela. The video presents the Venezuelan countryside as a serene paradise, belying the violence that has gradually suffocated the nation over the past 10 years. Hours after posting, Speer and her ex-husband experienced car problems. Stranded alongside the road, the chaos would soon consume her as well. Armed robbers peppered their car with small arms fire, extinguishing the promising lives of Speer and her ex-husband and leaving their 5-year-old daughter orphaned with a bullet in her leg. The high profile killings were just the latest in a country cursed with a soaring homicide rate, a problem that has rocked Venezuela to its core.

This garish act of violence catalyzed protests in a nation where so many endemic problems have gone unresolved. Beginning in January after the deaths of Speer and her family, the population has rallied against the government, seeking reprieve from the bedlam. In order to understand the vast public frustration and current developments, one must recognize the disturbing realities and contradictions of life in Venezuela.

First, Venezuela is now one of the most dangerous countries in the world. In 2013, 24,000 people were murdered, and 90 percent of those cases went unsolved. Armed robbery is commonplace, where there is one gun for every two people. Corruption and misappropriation of resources castrate law enforcement. Venezuelans are fed up with living in a virtual warzone. Economic problems compound this existential threat.

A hallmark of Chavez’s rule was leveraging the country’s oil reserves (the world’s largest) into subsidies for basic goods. He implemented price controls so that the poor could still afford the necessities, however, businesses grew unable to afford the imported products because they had to sell them at a price much lower than market value. Under Chavez, the economy wasn’t diversified, as oil accounted for 95 percent of exports. This legacy has continued to today, and thus imports are essential, because the country has little domestic manufacturing capacity. Leading up to the New Year, currency devaluation further deteriorated the economic situation as the price of imports spiked and inflation bled citizens’ finances. Currency devaluation reinforced the shortage-inducing price controls; necessities such as flour, sugar, and paper became in short supply. And then in January, the Speers double murder occurred and pushed the exhausted population over the edge.

Insecurity and shortages were unfortunate byproducts of his spending-obsessed socialist rule, but the last straw for many young Venezuelans was the 2013 presidential elections. After 14 years of Hugo Chavez’s reign, he succumbed to cancer and opened the door for political change. Yet, former Vice President and Chavez’s anointed successor Nicolás Maduro claimed the presidency with a narrow 1.5 percent margin of victory. The opposition claimed 3,200 electoral irregularities, but the Venezuela’s National Electoral Council found no fraud. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that like Chavez, Maduro legitimately curried the favor of much of the population. Chavez’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela has continued its dominance with Maduro. Despite his authoritarian approach to power, his 10-month tenure has affected little positive change for Venezuelans.

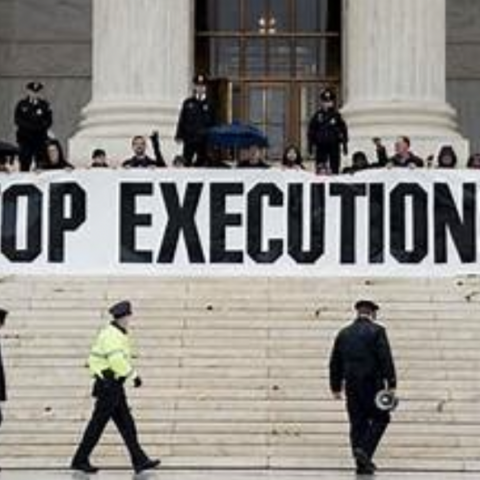

Now hundreds of thousands of students and demonstrators are filling onto the streets in a mass protest known as “La Salida.” Calling for the exit of Maduro from power and a new round of elections, anti-Maduro protestors aim to solve the problems that their government could not. Monica Speer’s murder sparked the first coals of outrage, but on Feb. 1, Harvard-educated opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez called upon students to protest against Venezuela’s chronic security, economic, and political problems. Students initiated the protests on Feb. 4 in the western city of San Cristóbal, but they have since spread to other major cities and the capital, Caracas. The Maduro government sees all public contempt as an illegitimate ploy by outside actors, namely the United States.

Chavez’s cloistered paranoia is alive and well within the Maduro administration. In fact, the anti-American flag, which Chavez proudly waved, has become a tool for Maduro to cement his reputation as a model of machismo in the mold of Chavez. Chavez’s death was reported as an American conspiracy, and now Maduro puts the blame on the United States for attempting a “soft coup.” The government perceives the United States as the instigator of student movements, which have spiraled into violence. However, the dead lie on the side of the youth, not the government.

The Chavistas have come out swinging in the cage match for Venezuela’s future. The Venezuelan National Guard and armed pro-government gangs set about curtailing protestors. As of February 24, 13 people have died at the hands of their own government. The New York Times wrote: “faced with a government that systematically equates protest with treason, people have been protesting in defense of the very right to protest.” Indeed, Maduro’s regime takes every opportunity to quell dissent. They have even gone as far to set militants known as collectivos upon journalists and foreign government envoys who aim to intervene. Holding shotguns to the heads of student activists only reinforces the absurdity of official Venezuelan tactics, but the military-style response to the protests continues.

The capital of Caracas is now a maze of makeshift barricades and trash fires. Students across the country amass in face of government-sanctioned violence to force democracy back into the Bolivarian Republic. They do not feel safe on their own campuses, and they now face retribution on the streets. However, not all Venezuelans are complicit in the demand for regime change.

At first glance, the protests in Venezuela bear striking resemblance to the revolution in Ukraine. Protestors are often not referred to as students but as fascists by the Venezuelan government – a similar tactic observed in Ukraine. However, U.S. social media advocacy for pro-democracy protesters distorts reality. Maduro’s fall will not necessarily repair the festering issues inherent in Venezuela. The culture of corruption did not begin with Chavez. Since the 1970s, corruption has consistently inundated Venzuela’s government and society. Regardless of whether the government is socialist or capitalist, corruption will persist and weaken reform.

Likewise, many citizens saw hitherto unseen benefit from Chavez’s rule. The lower classes and the impoverished witnessed previously unprecedented inclusion in policy-making and received much needed job opportunities. The reality remains though that means of production stay in the control of privileged upper class whether that was the capitalists in the pre-Chavez era or government officials under the current socialist regime. Students furthermore are not alone on the streets; some of the same armed bandits who murdered Speer have taken the opportunity to fight openly. Some government forces, too, work to restore some semblance of normality to daily life, while others use violence unconditionally.

Furthermore, South American nations stand in solidarity with the Maduro government in defense of “democracy.” Most South American states have leftist governments who admire Venezuela and condemn the protestors’ violent means in lieu of peaceful dialogue. Venezuela’s allies view the protests as a repeat of the failed 2002 coup, which deposed Chavez for only47 hours. International organizations such as the United Nations and the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America are pursuing a middle road. They’ve called for respect for the democratically elected government of Maduro, while recognizing that human rights infractions have occurred. Overall though, in a country with no real separation of government powers, meaningful reform and dialogue will remain difficult to achieve.

Maduro lacks the political sensibility of Chavez, and this has bolstered protestors’ resolve. The current president wants to match the protesters’ intensity blow for blow, unlike the former leader, who understood that fanning the flames would come back to burn him. Consequently, la Salida will not subside soon. The validity of Maduro’s government varies from person to person, but violence plagues the average citizen as dialogue fails to occur. The only remaining question is what the outside world can do to avert catastrophe.

Ultimately, political realities cannot be ignored. The ability of the United States to influence the current administration is nil. Describing Venezuelan-American relations as icy would be a resounding understatement. Outside pressure may yet shift the tides of Venezuela’s internal tension, but the likelihood of international condemnation is small. Venezuelans who desire change must put their faith in Maduro to dig his own grave. Yet, the opposition has been dealt a huge blow. Leopoldo Lopez, leader of the Voluntad Party which organized the protests, has been arrested as of Feb. 18 on trumped-up charges of inciting violence. The Venezuelan government has all but given up on its attempt to mask the crackdown.

As Maduro descends further into a labyrinth of lies to protect the legacy of Chavez’s Venezuela, the future of the state remains murky. Not all protestors are peaceful, and not all government forces are oppressive. Citizens from around the world may sympathize with beleaguered students, but this does not equate to foreign governments taking a hardline on the Venezuelan government. The deaths of Monica Speer and innocent students may yet be avenged, but without a black and white depiction of who is at fault, chaos will reign. The cries for freedom on Venezuelan streets may be drowned out by Sukhoi fighter jets soaring overhead, but Americans must first differentiate between rumor and fact if they want to effective assist embattled supporters of true democracy.