“Yesterday they chose between segregation and integration. Between isolation and being open. Between stability and uncertainty. And they chose the best option for everyone – for themselves and for Europe.”

If one had to guess who said the quote above referring to the results of the failed referendum over Scottish independence on Sept. 18, a prudent guess would be Prime Minister David Cameron or, more generally, a vehement unionist in another part of the United Kingdom. However, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy was the one who extolled the virtue of Scotland remaining part of the United Kingdom. His impassioned speech about quelling secessionist sentiments may echo throughout the world from the northern reaches of Quebec to the Kurds in Iraq. However, Rajoy’s speech resonated most powerfully within the borders of his own country. It represented his fear over the referendum for Scottish independence having a domino effect in Catalonia, a region in northeastern Spain with historically separatist tendencies.

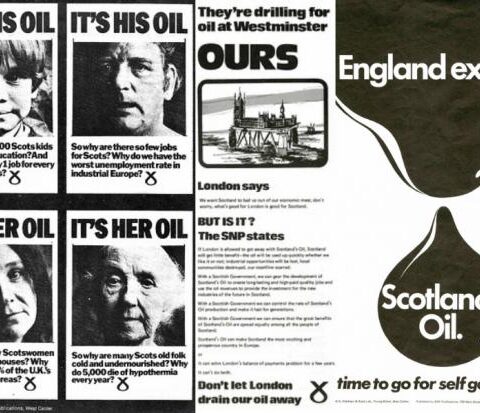

The region of Catalonia has been a part of Spain since its inception in the 15th century after the marriage of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella united Aragon and Castile. Although the Catalan state was integrated effectively into the Spanish state, a renewed sense of Catalan identity was created in the 19th century. This revival of Catalan culture continued later as a backlash against Francisco Franco’s repressive rule in the 1950s that included restricting the usage of the Catalan language. Relations between Catalonia and the Spanish capital of Madrid have become even more strained as of late due to a revitalized cultural and media campaign and a struggling Spanish economy. In fact, Catalan people feel that their particularly strong economy, comprising 20 percent of the Spanish economy and involving 16 percent of the country’s population, is being depressed by its unequal burden of taxation to Madrid. Catalonia has especially resented the elite rule of Madrid over its region since 2010, when the Spanish government struck down a statute granting more autonomy to Catalonia. Nonetheless, despite the failure of the Scottish referendum, the fact that a referendum even occurred is encouraging to Catalan people and has fueled an ever-growing nationalist movement.

To actualize such energetic calls for secession, Artur Mas, the elected President of Generalitat de Catalunya, and the Parlament de Catalunya voted on Sept. 19 to call a referendum for independence. The referendum has been tentatively scheduled for Nov. 9. However, there remains a problem with this upcoming vote; referendums that do not include all Spaniards are illegal in Spain, and thus a vote by just the Catalan people would immediately be struck down by the Tribunal Constitucional de España. Moreover, there are other distinctions between the situation in Scotland and the one in Catalonia that further undermine the Catalonian referendum.

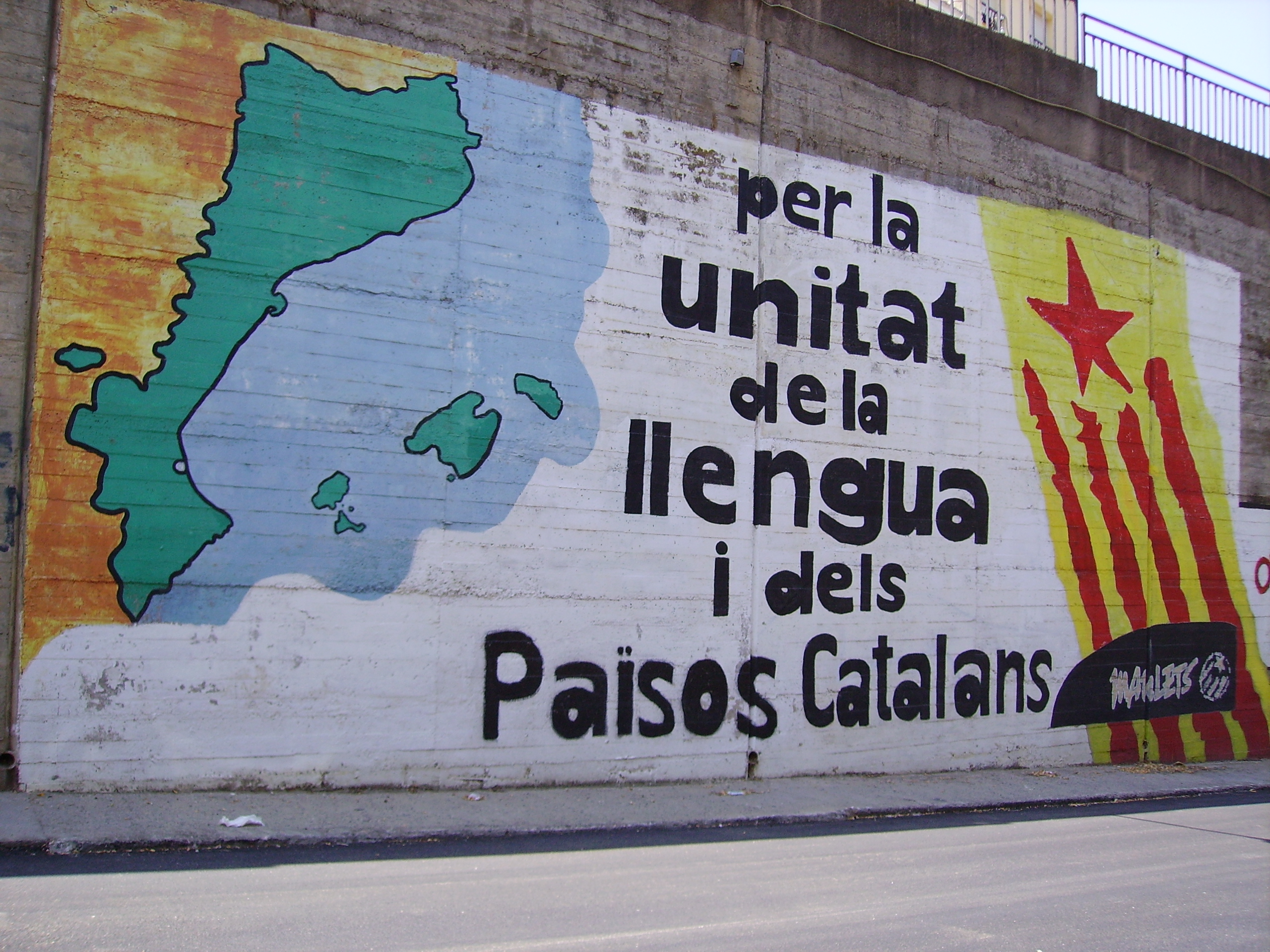

Both the British and the Scottish governments proposed the Scottish referendum, while Madrid is still refusing to sanction any referendum. Additionally, the Scottish independence vote was milder in its rhetoric, focusing more on political and economic powers, rather than nationalistic pride. Though there are political and economic concerns for the Catalan people, the movement is defined by underlying cultural differences; teachers, doctors, and public sector workers, in fact, are required to use Catalan as an official language. The fear of many in Madrid is that while there was no risk of Wales or Northern Ireland seceding from the United Kingdom if Scotland had declared independence, Spain could potentially lose Catalonia as well as the Basque region, another economic powerhouse of the Spanish economy. Another lurking concern is the Catalan separatists’ hope of usurping the Balearic Islands and Valencia in an effort to restore the greater Catalonia of the middle ages. And Spain without these two regions, and possibly without the Balearic Islands and Valencia, would be severely compromised both in the sense of economic productivity and political legitimacy.

As tensions mount between Catalan separatists and the Spanish government, there continues to be a disconnect between what can be done legally and what is being done in Catalonia. Although an illegal referendum conducted with the support of Catalan leader Artur Mas may not occur Nov. 9, it seems unlikely that the Catalan people will continue to bow to the central government in Madrid. In order to fan the flames of secession, Artur Mas needs to take a page out of the book of Scottish leader Alex Salmond and call for early Catalan elections that would provide a mandate for independence that would resonate with the leaders in Madrid. Without a clear mandate to the central government, Catalonia risks forgoing its current separatist fervor by simply falling prey to the intimidation tactics of Madrid yet again.