From the moment almost every college student sets foot on campus, he or she is inundated with a piece of advice repeated by professors, counselors and parents alike who are worried about the student’s future employability: “If you want a job after graduation, you’re going to have to find an internship in college!”

The truth of this advice is pretty indisputable in 2015. According to National Association of Colleges and Employers research, members of the class of 2014 were 35 percent more like to receive a full-time offer before graduation if he or she had internship experience. Thousands of companies, from tiny NGOs to the financial institutions of Wall Street, offer some sort of internship program, and nearly every college career center across the country spends ample amount time and effort to help students secure an internship.

However, when wading through dozens and dozens of online postings, there’s just one, small, pesky word that pops up again and again, dashing the hopes of many would-be applicants: UNPAID.

Barack Obama has been a proponent of increasing minimum wage nationwide for years. In 2014, the president signed an Executive Order mandating all contracted federal employees be paid a minimum of $10.10. Since his first presidential campaign until today, Obama has championed for increased wages for the poorest workers:

“In this country, it’s inexcusable. I can tell you firsthand that these men and women, they work their tails off, and they don’t complain. They deserve to be treated fairly. They deserve to be paid fairly for a service that many older Americans couldn’t live without.”

Barack Obama believes it is inexcusable for people to work hard at a full-time job all week and not earn enough to live a decent life.

Barack Obama’s White House interns are unpaid.

(Note: The White House communications office did not respond to email inquiries about this topic.)

The hypocrisy of not paying interns, who are expected to work “at least” 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday at the White House, extends beyond the president and extends far beyond politics; nearly every sector in every region of the country hires unpaid interns, and without much of a choice many times, students are more than willing to take an unpaid job for a few months in exchange for beefing up their resume.

This is not to say unpaid internships aren’t valuable to those who take them. According to UGA Career Center surveys between 2011 and 2015, an overwhelming 85 percent of respondents said their unpaid internship was an “extremely beneficial” or “very beneficial” experience. Internships, even if unpaid, are undoubtedly a strong boost to the resume of a recent graduate; that is, if you can afford to work one.

To many college students, the thought of working an unpaid internship during the semester or the summer isn’t too much of a burden. They probably weren’t working a paid job already, so an unpaid internship has no net effect on their income, just a net increase to their employability. For many other college students, though, the idea of working full-time and receiving no monetary compensation just isn’t feasible. According to a 2013 survey, nearly 80 percent of students held down a part-time or full-time job during school.

The overall effect of widespread practice of not paying interns is simple – the continuation of income inequality. Those who have a healthy enough bank account to spend a summer in Washington, D.C. paying for rent, food and transportation are free to apply for some of the most prestigious internships a college student can find. Those who don’t have the financial means won’t even send in a resume, despite their qualifications.

Returning to the White House internship, let’s take a look at a real-life example of this result. During the summer of 2015, the White House accepted 157 interns, all unpaid. Of the 157 interns, a staggering 76 percent hailed from private colleges. Nationally, only 23 percent of all college students are attending private schools. If it isn’t obvious that private colleges cost more than their public counterparts, according to the College Board, the average cost of a private university was $31,231 in 2014-2015, more than three and a half times the cost for an in-state public school.

While certainly many private universities, especially the top ones, offer generous financial aid, very rarely do they subsidize the approximately $5,800 it would set you back to spend three months interning in the capital, according to the Office of American States.

An unpaid internship creates such a strong barrier to entry that it perpetuates the growing income inequality in the United States, a topic seemingly near the top of the list in terms of importance during this election cycle. However, the fight to do away with unpaid internships has quickly faded since it reached its peak in 2013 after two interns won a class-action suit again Fox Entertainment, a decision which was overturned this past June.

Instead, millions of students are either forced to limit their search to paid internships, which are generally more competitive, or forego an internship altogether for lack of funds. While career centers are able to provide some support to students in this tricky situation, it’s difficult to replace the value of a full-time internship.

“If students are not able to receive a paid internship and cannot accept an unpaid internship, we would suggest a number of things for those students to consider. First, they should consider obtaining a paid part-time or full-time job while exploring potential ways to take on extra projects and/or developing transferrable skills to enhance their marketability. We would also suggest students consider externships or job shadowing experiences while employed in a paid part-time/full-time job,” Director of the UGA Career Center Scott Williams said.

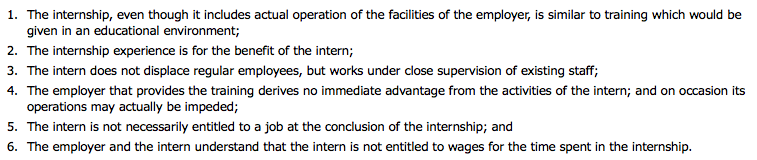

Last year, Columbia University and New York University changed internal policies to discourage students from accepting internships that do not comply with the Fair Labor Standards Act. At NYU, for example, the university stopped posting internships on their job board that don’t pass the FLSA’s test for legality and provided students with more resources about what constitutes a legal internship. The FLSA has six criteria for what constitutes a legal unpaid internship, with the two most noteworthy benchmarks being that an intern “does not displace regular employees” and provides “no immediate advantage” to the employer.

You don’t have to look very far into university-promoted job listings to find unpaid internships that don’t meet those criteria.

At the moment, the immediate horizon provides little relief to this situation. After the Fox Entertainment ruling in June, the courts seem unwilling to take on cases as class-action suits, so individuals would have to spend years in court to earn their minimum-wage back pay. Meanwhile, politicians, likely knowing it’s more important to stay in the good graces of business owners who can take advantage of the current environment than win over the low-turnout 18-24 crowd, have barely made a peep about interns’ rights.

The most logical solution is for universities to advocate on behalf of their students and, like Columbia and NYU, not award credit for or promote internships that do not comply with the FLSA standards. Taking thousands of students out of their candidate pool, rather than one-by-one because of financial concerns, is the only way to draw the attention of employers and change policies.

Further, groups of universities already have preexisting relationships that would allow a policy change to really force the hand of employers. You may just know them as football conferences, but these associations actually do extend beyond athletics. The Big Ten, comprised of 14 schools with a total of over 570,000 students, is renowned for its cooperative research programs.

Each year, Ivy League presidents convene to discuss future policies and initiatives at the eight universities. You can be sure the U.S. government would quickly begin following its own laws and paying interns if 60,000 potential top candidates were heavily discouraged from applying to their positions. Likewise, SEC presidents and chancellors have an annual meeting about topics important to the future of their universities.

If Barack Obama, politicians across America, and CEOs of every status are unwilling to take a stand on behalf of workers rights, it’s time for UGA President Jere Morehead and university presidents nationwide to act on behalf of their student bodies and the future of income equality in the United States and, instead of offering course credit, commit to eradicating exploitive and illegal internships.

Photo: Progressions: Hannah Giles / Department of Labor