By: Shornima KC

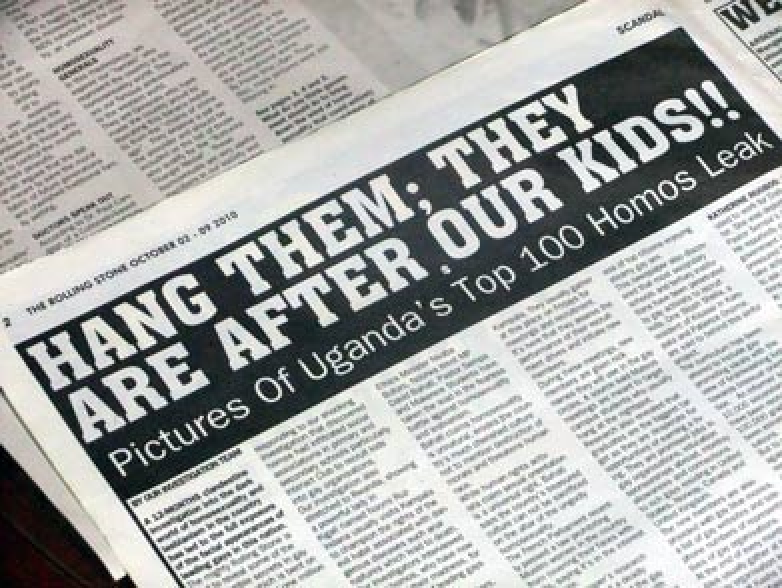

“Homo Generals Plotted Kampala Terror Attack” claimed a headline in a Ugandan tabloid in November 2010. More recently, Red Pepper, another popular Ugandan tabloid, used “Exposed! Uganda’s Top 200 Homosexuals Named” as their headline. Only three years ago, David Kato, an LGBT rights activist, was brutally beaten to death after a similar tabloid story outed him as a homosexual. The police chalked his death up to a botched robbery.

Though those headlines are from sleazy tabloids, they reflect the attitudes of many Ugandans towards homosexuality. Homosexuality is associated with pedophilia and the degeneration of society in Uganda. These attitudes have resulted in a recent anti-gay bill targeting homosexuals and any persons associated with the LGBT community.

On Feb. 24, 2014, Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni signed the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act. The bill, originally proposed in 2009, was called the “kill the gays bill” by the media due to the death penalty clause attached to it. As it stands, the law does not prescribe the death penalty for homosexuals, but does demand a lifetime prison sentence for engaging in homosexual acts.

This law poses obvious dangers for homosexuals in Uganda. The LGBT community in Uganda already lived in constant fear of hate crimes, but it is especially pronounced now that the government has openly endorsed a staunch stance against homosexuality. The law is laced with stringent, unforgiving language intended to inspire fear in homosexuals and any sympathizers. Worse, the language of this bill is easy to manipulate as some conditions for penalty are vaguely defined. For instance, the law states that “A person commits homosexuality if he or she touches another person with the intention of committing the act of homosexuality,” Intention is difficult to conclusively prove or disprove in court, which leaves more people vulnerable to prosecution. The law prompts a very dangerous witch hunt, especially with clauses that penalize anyone who does not report a homosexual act.

Additionally, another lurking fear is the effect these laws will have on AIDS/HIV awareness and the treatment of the patients since AIDS/HIV is still largely associated with the gay community in many African countries. Uganda made some great strides under Museveni in their fight against AIDS; in fact, his 27 years in office have seen the most effective battle against AIDS in Uganda. However, laws like this threaten activists who work to fight and eradicate the disease, since organizations who work with homosexuals can also be penalized.

Understandably, the international community and human rights groups are outraged at the passage of this bill, and Uganda is paying a hefty price. Foreign aid finances over half of Uganda’s budget and accounts for 13 percent of its GDP, so the international community can have some sway in Uganda’s domestic politics. Norway has pulled $8 million in developmental funds, while Denmark is redirecting $9 million to private sectors.

However, Ugandan troops are the main peacekeepers in Somalia, which makes cutting the entirety of foreign aid difficult. The United States and Britain, the two biggest aid contributors to Uganda, are not cutting aid, but are redirecting it in a manner that circumvents the government. Nevertheless, we are undertaking a review of our relationship with Uganda in light of this decision” said White House spokesman Jay Carney. Since the bill passed, Uganda’s shilling dropped 2.9 percent against the dollar. The shilling was one of the best performing currencies in Africa, gaining 3 percent against the dollar this year, but after this bill it faced the biggest decline in all currencies behind only Ukrainian hryvnia and Haitian gourde.

Rather than succumbing to international pressure, Museveni spun the rhetoric to favor him. A spokesperson for the administration says, “in the face of Western pressure and provocation” Museveni has shown Uganda’s independence. Additionally, popular media is aiding anti-gay sentiments and this bill by making anti-gay sentiments synonymous to patriotism. Initially, the bill did not fare well with Museveni. He hinted that he would not sign it when the bill was first presented, even though it was overwhelmingly supported by the parliament. Then, he opted to steer clear of direct decision decision-making by engaging a a panel of scientists to determine whether homosexuals are born naturally or are made so by their environment. He signed the law in front of scientists who determined homosexuality was not genetic. The flip in his stance comes as elections in draw near in the looming 2016 horizon. As popular opinions stands strong against homosexuals, he has more incentive to take a stand against homosexuality in order to remain in power. Additionally, this law distracts draws attention away from his Museveni’s increasingly authoritative authoritarian 28-year rule.

The bill is one of the most draconian in Africa, where only 18 out of the 52 countries legally allow homosexuality. African countries are generally moving to liberalize their economies, but they remain weak in protecting minority rights. Recently more African countries are moving towards anti-gay laws. In Mauritania, Sudan, and some parts of Somalia and Nigeria homosexuality is punishable with the death penalty. In these countries anti-gay laws are popular and the easiest way for incumbent rulers to distract from other problems.