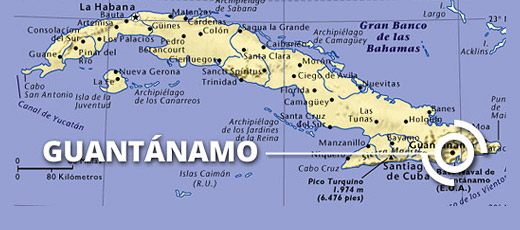

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba is home to the United States’ most notorious detention center. The Guantanamo Bay Naval Station, commonly referred to as Gitmo, has imprisoned more than 750 suspected terrorists since 2001. Declared as enemy combatants, these detainees, several of whom are American citizens, do not have access to the civilian court system. Gitmo is perhaps best known for prisoner abuse and torture under the Bush administration. While this mistreatment has been halted by the Obama Administration, there are still 112 remaining detainees who remain indefinitely imprisoned.

On Nov. 25, President Obama signed the annual National Defense Authorization Act. It prohibits the transfer of Gitmo detainees to the United States and makes it more difficult to transfer the detainees to other countries. Obama promised to shut down Gitmo in his 2008 presidential campaign, and he is reportedly considering executive action to close the prison with or without congressional support. In this article, GPR staff writers Shaun Kleber and Rob Oldham will present arguments for and against closing Gitmo. While they do not necessarily disagree on the underlying issues, they do approach it from two different points of view. Rob considers the tangible effects (or lack thereof) that shutting down Gitmo would have, given current political realities. Shaun takes a normative approach, advocating for how Gitmo and its prisoners should ideally be handled.

Keep it Open

By Rob Oldham

Barack Obama’s campaign rhetoric in 2008 was unequivocal.

“As President, I will close Guantanamo.”

He derided the Bush Administration for its human rights abuses in the War on Terror, saying “[Bush] puts forward a false choice between the liberties we cherish and the security we demand.”

Eight years later, one of his most famous campaign promises has not been realized, but it is not just because of resistance in Congress. The hopeful and inspiring civil libertarian we thought we elected in 2008 is no longer there (if he existed in the first place). During his presidency, Obama has not significantly curbed the infringements on liberty he accused Bush of violating. He has further put security first by maintaining the NSA’s phone and email surveillance program, using drone strikes to assassinate American citizens abroad, and indefinitely detaining suspected enemy combatants at Gitmo.

Now, as his presidency fades into the annals of history, Obama wants to unilaterally shut down Gitmo and score legacy points from the political left for protecting human rights. However, in his relentless pursuit to be viewed favorably by the history books (and social media commentators), Obama has failed to address the 800-pound elephant in the room: There is no compelling purpose to be served by closing down Gitmo. It would not advance human rights. It would be toothless symbolism that refuses to recognize the moral complexity we continue to face in the War on Terror.

Most of the liberal objections to Gitmo originally concerned its shameful legacy of torture and prisoner abuse. This issue became largely irrelevant after Obama took office. Just two days after taking office, he issued an executive order that limited interrogators to humane questioning laid out in the Army Field Manual. Although there are allegations that the Obama Administration has simply outsourced torture to our more willing allies, it is generally acknowledged that the Bush-era abuse of prisoners has been largely eliminated from military prisons.

If we accept that systematic and officially sanctioned torture is gone from military prisons (and it was by no means limited to Gitmo), the main criticism about Gitmo now is that the detainees are indefinitely imprisoned and have no access to a fair legal process through which they could advocate for their release. This is not completely true. During the Bush years, detainees were tried by military commissions. Distinct from civilian courts and military tribunals, military commissions allow suspected terrorists to be tried without the full legal rights that a U.S. citizen accused of a crime would expect. Only two-thirds of the jury must agree to convict, the standards of evidence are lower, and acquittal is by no means a guarantee of release. The Supreme Court rejected several parts of the military commission system in the 2008 case Boumediene v. Bush. They ruled that detainees must be afforded habeas corpus rights so they can challenge their detentions before a federal judge. However, the Supreme Court never said anything about the detainees having the right to access all of the protections of the civilian court system. They do not have these rights and there is good reason for it.

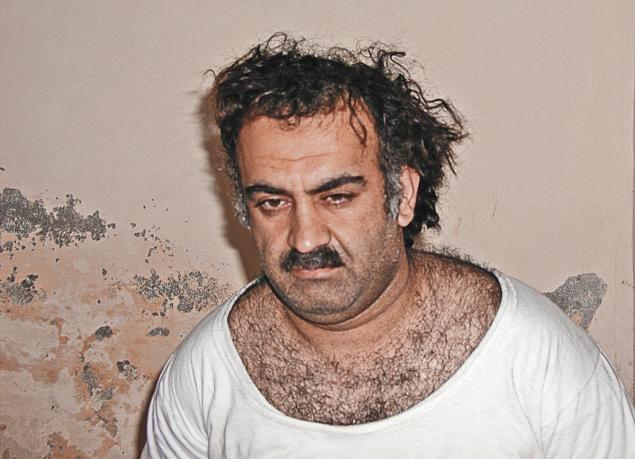

Obama discovered the impracticality of publically trying terrorists for their crimes when he attempted to bring 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed to a civilian trial in New York in 2010. Attorney General Eric Holder believed that Mohammed and several of his compatriots could go to federal court and receive a fair trial just like any American citizen accused of a crime. However, they overestimated the American public’s affinity for terrorists receiving full legal rights. There was an outcry and Obama soon gave up the plan. After this debacle, the Obama Administration accepted the obvious: Civilian courts are for criminals, not terrorists captured in war zones. It was not clear that the process used to gather evidence in the War on Terror would be admissible in a civilian court. Securing admissible evidence and proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt should not concern military leaders when they hunt terrorists in foreign war zones. Imagine the disaster if Mohammed had been freed on a technicality concerning the evidence chain or Miranda Rights. If the trial were going to be anything but a farce, Obama would have to respect the court’s decision, even if it led to the release of a dangerous terrorist. This would have been unacceptable and possibly detrimental in the precedent it set for how the U.S. dealt with prisoners of war.

After the Mohammed trial debacle, it became clear that Gitmo detainees could not have legitimate trials, but also could not be released. Obama recognized this and in 2011 ordered the creation of Periodic Review Boards that would determine whether detainees would be released or indefinitely detained. The prisoners who cannot be released are in legal limbo. They are not like traditional prisoners of war who are freed when a conflict ends. The War on Terror might never end, and certainly will not in the lifetime of the detainees. Obama is a realist and is surely aware that whether they are in Gitmo or another prison, most of the detainees will never leave the custody of the U.S. military.

Despite his public reluctance to deny these men a trial, Obama is right to keep them imprisoned. Gitmo detainees are no shrinking violets. They are dangerous terrorists and it doesn’t appear that they have been softened by their detainments. Earlier this year a report from the Director of National Intelligence confirmed that 116 detainees who were released or returned to their home country have since returned to terrorism. At least three of the five detainees who were exchanged for Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl in 2014 have tried to “re-engage” with their old terrorist networks. Obama is wise to ensure that the remaining detainees do not have that opportunity. They could be useful as propaganda tools, morale boosters, or even instruments of attack. As seen in the recent Beirut suicide attack, it only takes one person with a bomb to kill scores of innocents.

So, if torture is no longer prevalent, the civilian court system is off-limits, and it is fairly clear that their indefinite detainments will continue regardless of where the prisoners are being held, what is the value in closing Gitmo? The military has invested millions of dollars in creating a secure prison in southeast Cuba. It is a strategically valuable location that keeps prisoners far from U.S. soil and the Middle East, where the danger of escape or attack is always present. The answer is that closing Gitmo solely benefits Obama and his approval ratings, not the American public and certainly not the detainees.

Banning torture was true moral leadership. Shutting down Gitmo is smoke and mirrors, mere politicking and false symbolism rather than substantive policy change. It would not make a difference for detainees and would advance the false narrative that America is ready to move on from its checkered past in the War on Terror. We are not, and Obama knows it. The President’s rhetoric paints him as a champion of liberty, but, in reality, he has done little to move us from George W. Bush’s central axiom in combatting terror: We are at war, and the normal rules of law do not apply to our enemies. Obama the candidate would have been appalled by this lack of moral clarity during wartime. Although he sometimes pretends to be, Obama the president is not so naïve.

None of this is to say that the status quo for the detainees is ideal. If the military eventually finds a way to give terrorists greater legal protections without hindering national security, then perhaps it would be better to close Gitmo. It remains the face of brutal torture, indefinite detainment, and limited legal rights, all affronts to our national character. In the best possible world it would not exist. In the real world, though, it must exist. Gitmo and other military prisons serve strategic functions necessary to defeat global terrorism. Gitmo’s practicality overrides any false symbolic victory that closing it would afford.

And if symbolism is really that important, we should still keep it open.

Gitmo represents our country’s ambivalence in trying to preserve both liberty and security during the War on Terror. Many Americans refuse to acknowledge that we sometimes give up some of one to get more of the other. But like it or not, we do make those compromises. Our government has decided that giving terrorists full legal rights during wartime is impractical and unsafe. This is a calculated decision to impede liberty in the interest of security. No one understands this better than Obama. Closing Gitmo allows him to dishonestly conceal the continued detainment of our enemies without constitutional rights— a dark, but necessary, side of war. Keeping Gitmo open shines a bright light on this darkness, forcing our leaders to face their own moral compromises made in the post-9/11 world rather than allowing them to hide behind empty political gestures.

Close it

By Shaun Kleber

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Socialist.

When the Constitution was signed, this country’s founders inscribed certain inalienable rights—rights that were guaranteed to each person, rights that could not be violated by a truculent majority. But here we are, over two centuries later, a country driven by fear, willing to look the other way as our government violates those exact rights in its handling of The Bad Guys. These violations are often excused with the exact argument that Rob made above—that they are necessarily evils of war—but this excuse is a dangerous one because of the potential for intentional abuse and unintentional missteps.

Allow me to introduce you to the Uighurs, Mr. Oldham. A small group of this Muslim ethnic group concentrated in Western China fled brutal persecution by the Chinese government and ran to a preexisting Uighur community in a Taliban-controlled region of Afghanistan. They were caught by American forces in 2001 and sent to Gitmo under suspicion that they were associated with al-Qaeda or the Taliban. The suspicion was baseless and inaccurate, but the truth holds little weight at a prison that has been described as a “legal black hole.” It took two years for the military to acknowledge its mistake and clear the 22 prisoners for release. It took another three years before the first Uighurs were released, and it was not until 2014 that the last of the Uighur prisoners were freed.

Thirteen years at Guantanamo. For nothing.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

I understand that the politics are difficult, but they are not impossible. With enough attention to this issue, with enough focus on its stain on American values, Guantanamo can be closed, and it needs to be closed. Not for Obama’s legacy. Not because of the exorbitant cost. Not for “toothless symbolism.” But because it is a gross violation of the values and morals that are the backbone of this country. Our character as a country is not defined by how we treat our friends; it is defined by how we treat our enemies—by how we respond to challenges and adversity and how we handle the people we hate the most.

The American judicial system protects certain rights and procedures for good reason. The right to counsel and a speedy trial, the protection against torture and other unfair interrogation tactics, the burden on prosecutors to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt—these rights and more ensure that innocent people are protected from persecution while those guilty of crimes are still able to be punished. Those accused of criminal conduct have a mountain of rights and protections, because we would rather 100 guilty people walk free before we wrongly imprison one innocent person and unfairly revoke the liberties and freedoms we hold so dear.

Consider the government officials, law enforcement officers, and human rights activists who steadfastly protect the rights of groups like the Westboro Baptist Church and neo-Nazis to promote their hateful messages. They do not do this because we value those messages, but rather because we value their right to express them. If we allow ourselves to ignore these core values and violate these critical rights in a particular instance, then where is the line? When else may we violate these rights?

The question of where to draw this line sets up an army of straw men. If we’re willing to indefinitely detain the prisoners in Guantanamo, who is next? If we’re willing to outsource imprisonment for people who present a danger to our society, when will we begin doing this for serial killers? Rapists? Thieves? Domestic abusers? Juveniles? The questions are endless, and I have no desire to inflate this argument into exaggerations and dystopian what-ifs. The problem, however, is that in times of war and distress, these straw men have an unfortunate habit of coming to life. Japanese internment camps, the torture previously used at Gitmo, and even Donald Trump’s recent rhetoric about a Muslim registry come to mind.

Rob raises the argument that the prisoners held at Guantanamo are not American citizens, which is an important distinction when discussing legality and rights. However, while this may legally excuse their harsher treatment and dampen the fears of this treatment being extended to American criminals, the problem with this argument, as Noah Feldman writes in a Bloomberg article, is that “fairness demands regularity.” Each generation cannot choose a particular instance to cut corners and ignore human decency and expect future generations not to do the same. We cannot turn on and off our values and morals as we see fit—and if we do, that erosion will only worsen with time.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Jew.

There are very real, practical concerns associated with closing Guantanamo, and they are not to be taken lightly. Just as there were very real national security concerns that led to the opening of the prison, which also should not have been ignored. But in addressing these concerns, the violation of basic human rights must be an absolute line we cannot cross. Yes, there are international laws that provide exceptions to these rules in the temporary handling of enemy combatants, but using those laws to justify indefinite detention without charge is a clear violation of the spirit of those laws, which were designed in the era of traditional, finite conflicts between international parties that could be resolved with a peace treaty—not the seemingly endless war of ideas we have now.

There are two distinct groups that must be considered in figuring out how to close Guantanamo: the 48 prisoners cleared for release to other countries, and the 49 others considered too dangerous to release—the “forever prisoners,” as they are called. There are also an additional 10 prisoners in various stages of legal proceedings, but they will ultimately fall into one of these two categories.

The way forward regarding the prisoners cleared for release is simple: release them. Make it a priority to either repatriate them to their home countries, if the security conditions are stable, or, if not, find another place for them to resettle. In order to be released, each prisoner must personally be cleared by the Secretary of Defense, who must find that the threat posed by each new release can be managed. This understandably creates a disincentive for the Secretary to act—it is much easier politically to maintain the status quo than worry about shouldering the blame if a former detainee were to reengage in terrorist activity. But that is no excuse for inaction—these prisoners have been cleared for release, and these orders from courts and the military must be respected.

The prisoners who have not been cleared for release—those who present a demonstrable danger to American citizens and interests—are a slightly more complicated case. The goal here should be to try and convict these individuals for their crimes in federal court and then imprison them in our highest-security prisons, whether they are American citizens or not. Federal prosecutors have won convictions in roughly 200 terrorism cases since 9/11, and these convicted terrorists have been held in prisons with the “supermax” security classification. One such prison is the Federal Correctional Complex outside Florence, Colorado, which is home to the United States Penitentiary Administrative Maximum Facility (ADX). This prison hosts a “who’s who” of America’s most feared prisoners—terrorists, serial killers, bombers—and the idea that convicted terrorists housed in a domestic supermax prison would pose a greater danger to American citizens than they do from Guantanamo is ridiculous.

Rob argues that it would be a disaster if a terrorist were to be freed on a technicality—which it certainly would—but as frightening as it may be to face the possibility of terrorists being acquitted, the alternative of allowing our government to pick and choose when to waive the right to trial and indefinitely detain people arbitrarily is even more frightening. We cannot recreate processes and precedents for each case, because they only hold weight as long as they are respected across cases—even when the outcome may be difficult to swallow.

Certainly, this would be a politically unpopular move that would incur a vitriolic response from Congress—especially congressional Republicans—but administration lawyers have long claimed that Obama, as commander-in-chief, has the power to act unilaterally in handling Guantanamo prisoners. The former special envoy overseeing Guantanamo’s closure, Cliff Sloan, and former White House counsel Gregory Craig wrote in a Washington Post commentary that “the president has exclusive authority to determine the facilities in which military detainees are held.” And some experts claim that if Obama were to issue an executive order moving Guantanamo prisoners to a military prison on U.S. soil, the detainees would likely have more success arguing for their right to a speedy trial.

Closing Guantanamo certainly would be a symbolic gesture, as Rob argues. It would signal to the world that we recognize our past transgressions and are moving to address them. It would remove some of the blatant hypocrisy from our calls to other countries to cease and desist their unfair criminal justice practices. But it would not be purely a symbolic gesture. There are real people’s lives at stake here, and even if we may not care about their well-being after what they may have done to our country and countrymen, we must never lose sight of the values that are buried in our treatment of them.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Our commitment to justice and fairness must never waver, because once it does—once we stop speaking up for others just as strongly as we speak up for ourselves—we lose what makes us American.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.