By Cole Mullis

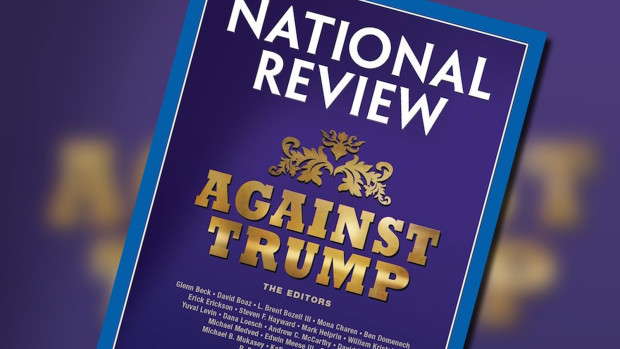

On Thursday, January 21, 2016, the National Review unleashed a concerted assault by a host of conservative commentators on the GOP frontrunner, real estate magnate and celebrity candidate Donald Trump. The writers condemned Trump’s perceived inconsistency, his inflammatory rhetoric, and his policies, which they consider left-leaning.

This is not the first time that the magazine has attempted to excommunicate the Party disloyal. For decades, the Review has been the primary shaper of mainstream conservative orthodoxy. It has been its mission since the 1960s to make “conservatism intellectually respectable and politically palatable” at a time when the Left has dominated intellectual circles. In the Review’s crusade for respectability, a once intellectually diverse, right wing became much more narrow. The magazine used its near-monopoly on conservative media to shape the modern neoconservative movement as we know it. In this narrow conservatism, there was no room for noninterventionists, libertarians or other outliers they deemed “kooks.”

Fast forwarding to 2016, some might reasonably question the National Review’s moral authority to define conservatism. In their wooing of intellectuals, neoconservatives have lost the populace. For most of the 20th century, the plurality of the politically-minded citizenry has been conservative. Today, the number of conservative-identifying Americans has declined steadily, and now just as many Americans identify as liberal as conservative. Recently, National Review Online released articles supporting gay marriage legalization and pedophile tolerance, hardly winning issues for the average conservative voter, and certainly not within range of Joe Six-pack’s orthodoxy.

The conservative electorate today is shifting away from the party line that the National Review helped establish. Americans, and especially conservatives, reject the GOP establishment’s moderate stance on immigration: fifty percent of conservatives and forty-one percent of Americans want visa issuances reduced. Despite the conservative media’s claim that free trade is a conservative policy, most conservatives favor a more protectionist approach. Eighty-seven percent of conservatives opposed the fast-track for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, an initiative supported by Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) and the Republican Establishment. One could argue this is just tribal partisanship against any proposal made by President Obama, but the decline in conservative support for free trade began around 2005, and steadily got worse before Obama’s term. Furthermore, Americans are largely turning against the interventionist “neocon” policy of the previous decade: sixty-one percent say the United States has no responsibility to help Ukraine and Republicans are strongly opposed to intervention in Syria, even more so than Democrats. Again, this can’t merely be chalked up to partisanship, as conservative support for higher military spending has actually increased throughout Obama’s presidency. This seems to echo Trump’s foreign policy: make the military so big, you never have to use it.

This rejection of the conservative establishment’s policies no doubt has a major role to play in the much-debated rise of Trump. Donald Trump’s key issue is immigration. He is also popular for his trade policy, where he describes himself as a “nationalist.” And his foreign policy hardly resembles the Wilsonian nation-building policy of the Bush administration.

Shortly before dropping out of the race, Jeb Bush refused any alliance with Putin, and promised escalation in Syria, whereas Trump promised cooperation, a relationship of mutual respect, and leaving Russia to their separate campaign against ISIS. Trump proudly flaunts his history of opposition to the Iraq War, and had particularly harsh words for President Bush shortly before the South Carolina primary. Conservative commentators were certain that this would cost him the Palmetto State, where the former president maintains an 84 percent approval rating. Once again the respectable right’s objections are full of sound and fury, signifying nothing: Trump swept the primary, taking all 50 delegates. Donald Trump continues to dominate the primaries, even as his campaign favors “foreign policy realism” over liberal interventionism. Either Trump really is invincible, or neoconservatism is losing its priority policy status for the conservative base in favor of “America First” nationalist policies.

The fall of the establishment does not only apply to Trump. Both parties are experiencing major upsets as the establishment candidates struggle to contend with the outsiders. The “respectable” candidates flounder, and in some cases, flop: before dropping out, establishment darling Jeb Bush was struggling to break into double digits in the polls. Marco Rubio is struggling to maintain second place in Florida, his home state. Meanwhile, Bernie Sanders is making slow but steady gains in the Democratic primary.

Perhaps, this is evidence of the natural evolution inherent in a two-party system: realignment of values to fit the needs of a changing electorate. It may well be that in the coming decades the American political landscape will more resemble the European one: the left characterized by multicultural socialism, the right by anti-immigration, non-interventionist nationalism.

If this election is not a fluke, it will be necessary for the conservative media to either exercise their full authority to combat this change, or embrace it, changing their rhetoric to better match that of their audience. In all likelihood, the National Review’s assault will fail to “stump the Trump.” In fact, it may end up helping him: a united media front opposing him will confirm the suspicions of those who support Trump for his outsider status. In the future it may well be that it’s the neoconservatives and the free-traders that get purged from the Review. They’re just not respectable anymore.