By: Shuchi Goyal

Photo: Getty Images

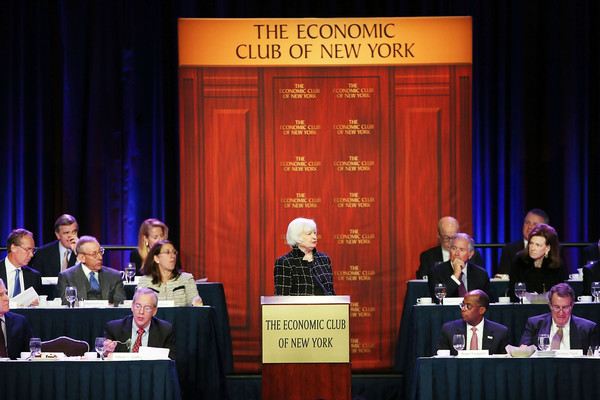

Less than a week remains until Janet Yellen officially ascends to her new post in the American government, earning a regal title both highly respected and closely scrutinized: the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The heir apparent to current Chairman Benjamin Bernanke will take charge of the United States central banking system on Feb. 1, renewing hope for reform to Americans who are still waiting for the economy’s post-recession lethargy to subside.

Yellen is no stranger to the Federal Reserve, which dictates the nation’s monetary policy in order to shift interest rates, inflation, and unemployment in favorable directions. She served as a member of the Board of Governors, a body of individuals appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate to preside over the Federal Reserve, from 1994 to 1997. Later, she became the president of the Twelfth District Federal Reserve Bank in San Francisco, before President Barack Obama appointed her as vice-chairman of the board in 2010.

Nevertheless, when Obama nominated Yellen to succeed Bernanke last October, it was widely understood that she had not been his first choice for the job. Obama’s top choice for the position of Chairman had been Lawrence Summers, who served as Secretary of the Treasury under Bill Clinton between 1999 and 2001 and had worked closely with the Obama administration during its response to the recession in 2009. However, Summers faced backlash from senators on both sides of the political spectrum, several of whom assured Obama that they would not support his nomination. Some felt that his policies as Secretary of the Treasury had indirectly played a role in the economic downturn years later. Others resented his close ties to Wall Street and bias toward the upper class in his policies. The opposition eventually grew so strong that Summers withdrew his name from consideration in September, citing the fact that he wanted to avoid an “acrimonious” confirmation hearing in front of the Senate. It was then that Obama shifted his attentions to Yellen.

Although she may not have been Obama’s first choice, Yellen received a a much warmer response from the Senate than Summers. Her familiarity with the Fed is certainly reassuring, particularly to those tired of the government lagging on reform. Her colleagues acknowledge her as an independent and methodical thinker who is able to assess long-term effects of policy changes better than many of her peers. Neverthless, Yellen’s job as she steps into the role of Chairman is markedly different from that of her predecessors. For example, when Bernanke took the position in 2006, unemployment was at a mere five percent and the housing bubble was still growing; few people predicted the recession that would rattle the nation less than three years later- few except Yellen, that is.

Aside from a few hiccups, Bernanke has generally received positive feedback for the way he alleviated the major immediate effects of the financial crisis during his two four-year terms. Yellen’s job now is to make the transition from Bernanke as seamless as possible and to restore consistency and reliability to the U.S. dollar, a victim of congressional fiscal policy. Because the United States is still a leader in international trade, stabilizing the dollar is crucial for maintaining peace in the global market.

Making a smooth transition should be easy enough, as Yellen worked with Bernanke for several years. She will likely continue to implement Bernanke’s low interest rate policies, which are expected to increase employment while also keeping inflation rates stable. However, Yellen also brings with her characteristics that serve to distinguish her from any of the prior holders of her office. For one thing, she is the first woman to serve as Chairman; more importantly, however, she is also the first Chairman to openly follow the Keynesian economic theory when addressing reform, as opposed to, say, the Neoclassical or Chicago schools of thought. So, although the business cycle naturally goes through periods of economic recession and expansion, Yellen believes that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies – that is, policies that adjust interest rates and the supply of money available for transactions- can mitigate the effects of these swings, rather than Congress’s structural policies such as education reform or fiscal changes.

Perhaps Yellen’s greatest challenge as Chairman will be restoring confidence in the American population. As gas prices fell and automobile sales rose, news outlets report strong growth in the economy. Yet, the majority of the population remains unconvinced. Last December, unemployment reached its lowest point in five years, at 6.7 percent. However, this figure does not stem from job growth, but rather from a combination of underemployment and an increase in the number of individuals leaving the job force entirely due to sheer discouragement. The stock market boomed in 2013, but only half of the population is investing in it. Businesses expanded, but workers’ wages increased by a measly one percent from 2012. It is consequently of no surprise that at the end of last year, nearly forty percent of Americans believed that the economy had in fact gotten worse, not better.

The end result of this wariness among consumers is that, in anticipation of hard times, they have become less willing to make investments and are more intent on saving, adding another obstacle to economic recovery. Yellen must wield the Federal Reserve’s policies in a way that will boost overall consumer confidence and allow interest rates to return to normal levels rather than being kept artificially low. The task is much easier said than done, and it will be Yellen’s true test for the next four years.