By Shuchi Goyal

This article appeared in the Fall ’16 edition of the Georgia Political Review.

In the weeks leading up to the 2016 Academy Awards, the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite trended across the internet, criticizing the lack of minority representation among nominees. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hoped that African-American show host and comedian, Chris Rock, would alleviate some tension. Instead, resentment deepened when Rock introduced three unsmiling, non-speaking East Asian and Jewish children on stage as accountants supporting the ceremony, playing to the stereotype that people of these ethnicities are money-obsessed.

Rock and the Academy were immediately criticized for offensive jokes that showcased “a tone-deaf approach to [the] portrayal of Asians.” Others, however, saw it as harmless jab that followed a long trend of incorporating race into comedy. The line between good-humored entertainment and blasé offensiveness is tricky and shifts with culture. The stony reception to Rock’s joke at the Academy Awards indicates that stand-up comedy in the United States is struggling to keep pace with ever-changing perceptions of race.

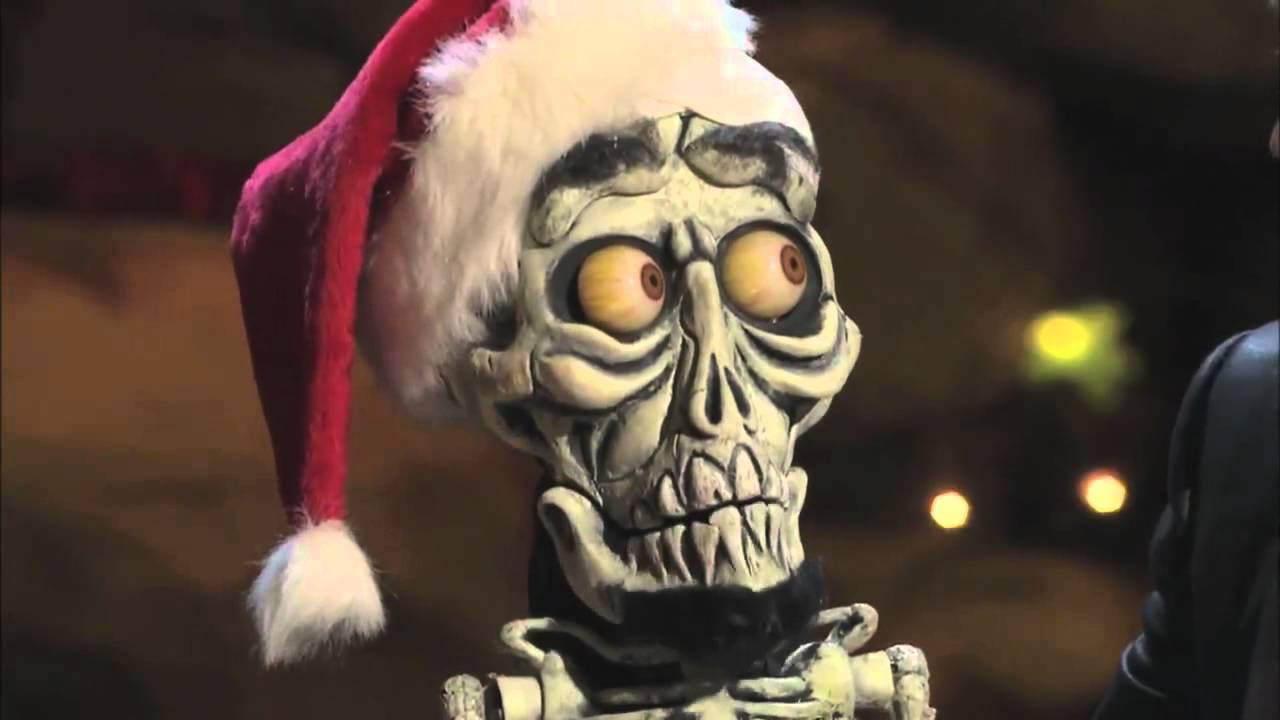

Just 10 years ago, the country may have reacted differently to Rock’s performance. In 2007, well-known comedian Jeff Dunham introduced a new character to his cast of ventriloquist puppets: Achmed the Dead Terrorist was an immediate crowd-favorite. Within two years, over 200 million YouTube viewers had discovered Achmed, his devotion to Islam, penchant for suicide bombings, and doleful catchphrase, “Silence! I kill you!”

Around the same time, Indo-Canadian comedian Russell Peters gained popularity among minority audiences. With a knack for imitating stereotypical East Asian and South Asian accents, Peters enumerated the cultural gaps of growing up in Asian homes versus white homes. Some of his most famous jokes concern the differences in how Asian and white parents discipline their children.

Many of Peters’ biggest fans were second-generation members of the race groups he teased. At the time, these audiences related to Peters’ anecdotes, which described minority experiences different from those of white families. Retrospectively, however, many of Peters’ performances feel cringeworthy. His exaggerated accents, which mock clueless Asian parents as they scold their high-achieving but exasperated children, reinforce the model minority myth; in Russell’s routines, Asian Americans are academically accomplished but ultimately severe, cheap, and humorless.

It is difficult to imagine Dunham and Peters receiving the same positive reception today as they did at the peaks of their fame. Yet it is also difficult to imagine that until the 1950s, blackface and other physical caricatures of colored people were popular features of mainstream American stand-up. Clearly, the interweaving of race and humor in the United States has a long and tangled history. The messy knots become apparent only in retrospect.

Does this mean that jokes about race have lost their place in comedy entirely? Maybe not. For every comedian who has built a career off of “othering” minority groups, there are others who have effectively wielded the mic for minority empowerment. In the 1980s and ‘90s, Dave Chappelle, Eddie Murphy, and even Chris Rock himself began their standup careers recounting their absurd experiences with anti-black prejudice in America. At the time, this approach, with its bold display of uncomfortable truths, seemed novel and captured audience attention. Thirty years later, other comedians have followed in these footsteps to achieve similar recognition for their work. Although they address similar themes of casual racism and ignorance, prejudice is a subject that gets more ridiculous the longer it exists. As a result, jokes on the topic age well, and audiences are laughing harder than ever.

There are too many comedians to list who have brought attention to race, class, and gender relations in the United States, but several names are iconic. Margaret Cho, for example, launched her career talking about being a Korean-American in 1970s and ‘80s California. In the late ‘90s, George Lopez and Gabriel Iglesias gained fame while focusing on their experiences as Chicanos in America. More recently, comedians Hari Kondabolu and W. Kamau Bell teamed up in podcasts and stand-up performances to highlight the impact of internalized racism in minority ethnic communities. Much of Kondabolu’s material has been in response to reports of police brutality against black Americans. To those who accuse Kondabolu of creating racial tension through his comedic focus, he responds: “Saying that I’m obsessed with race and racism in America is like saying that I’m obsessed with swimming while I’m drowning.”

Many of these comedians refuse to fake accents. Instead, they flip the narrative. While previous comedy focused on laughing at the “strangeness” of minority Americans, the new punchlines on race redirect attention to the ludicrousness of 21st century racism. Through satire, stand-up comedians have reached new audiences and promoted discussions about the country’s social and political climate.

It would be a mistake, however, to assign these performers the monumental task of leading society toward greater cultural acceptance; that responsibility should belong to our politicians and policy makers. But while the United States has recently been rattled by evidence of disturbing racial dynamics, partisan stalemates stall actual government action. Until political leaders are ready to combat racial prejudice head-on, maybe the best we can do is laugh about it.