By Ben Butin

Criminal justice reform has become a key component of Governor Deal’s administration and will remain a part of his legislative legacy. Over the past few years, Georgia has helped to lead the country in reforming criminal justice policy through many sentencing and correctional improvements that have gained bipartisan support. Georgia’s reform policies have benefitted the adult criminal population and the juvenile justice system, while also reducing criminal reentry across the state. Through evidence-based research, policies have been enacted to reduce the taxes spent on the criminal justice system as well as to reduce offender reentries, crime rates and non-violent offender incarceration. This has saved the state roughly$264 million tax payer dollars.

In the 1990s, Georgia citizens developed a fear of crime, reflecting the national approach towards crime at the time. This fear led Georgia as well as many other states to develop excessively punitive and short-sighted criminal policies. These policies emphasized incarceration for both violent and non-violent crimes and included many mandatory sentencing laws for violent offenders.

Georgia adopted the “seven deadly sins law,” which established a ten-year minimum sentence without parole for seven serious felonies. Another policy included the “two strikes law,” which required anyone convicted of a second “deadly sin” to receive a sentence of life imprisonment without parole.These policies caused a growth in the prison industry, resulting in the increase of Georgia’s average daily prison population from 11,554 people in 1980 to 52,806 in 2007. This rise in the prison population required a $335.2 million increase in expenditures for the Georgia Department of Corrections; in 2007, total corrections spending reached its peak–around $1 billion.

In response to the high levels of government spending on these corrections, Governor Deal pledged in his inaugural address to take a step towards expanding probation and adding new policies for non-violent offenders in order to decrease the escalating costof the prison system for Georgia’s taxpayers.

The Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform formed by House Bill 265 implemented new policies as the first concrete step towards a fiscally responsible prison system and led to new policy plans for non-violent offenders. This council began research on the complexity of Georgia’s criminal justice system in hopes of creating policies to reform the incarceration of non-violent offenders. The council found that nearly 60 percent of all individuals admitted to prison were drug or property offenders, and the main issue behind these offenses was the scarcity of community-based optionsandaccountability courts. For example, the state’s drug courts did not even cover 50% of its counties. After reviewing all the data, the council recommended new legislation be passed to expand evidence-based practice in criminal policies, to create new accountability courts, and to make supervision agencies adopt practices proven to help reduce recidivism. In response to the recommendations, House Bill 1176 was introduced in the Georgia House.

The bill focused onfour major areas in need of improvementin the criminal justice system. These included clearing prison space for serious offenders, reducing recidivism by strengthening probation and alternative sentencing options, relieving local jail crowding, and improving performance measurement.In order to decrease the cost of the prison system, the bill focused on redistributing prison beds to serious offenders, while giving shorter sentences with more supervision to non-violent offenders. HB 1176 attempted to do this by creating differing degrees of crimes, revising the approach towards penalties for possession of drugs, and reinvesting money to help judges with creating assessment tools for non-violent offenders. Drug and mental-health courts were created to identity high-risk offenders, and new accountability courts were formed to reduce recidivism rates. An estimated $11.6 million dollars were reinvested in accountability courts, and $5.7 million in the Residential Substance Abuse Treatment program.

This influx of money to recidivism programs helped reduce the number of people imprisoned for parole violations from 2,627 in 2012 to 2,298 in 2016. Because of the increase in accountability courts and residential abuse treatment programs, the rate of non-violent crime decreased from 3,575.9 per 100,000 individuals in 2011to 2,943.1 in 2016. Violent offenders also began to occupy most of Georgia’s prison beds, moving from 58 percent of all Georgia prison beds in 2009 to 68 percent in 2017.

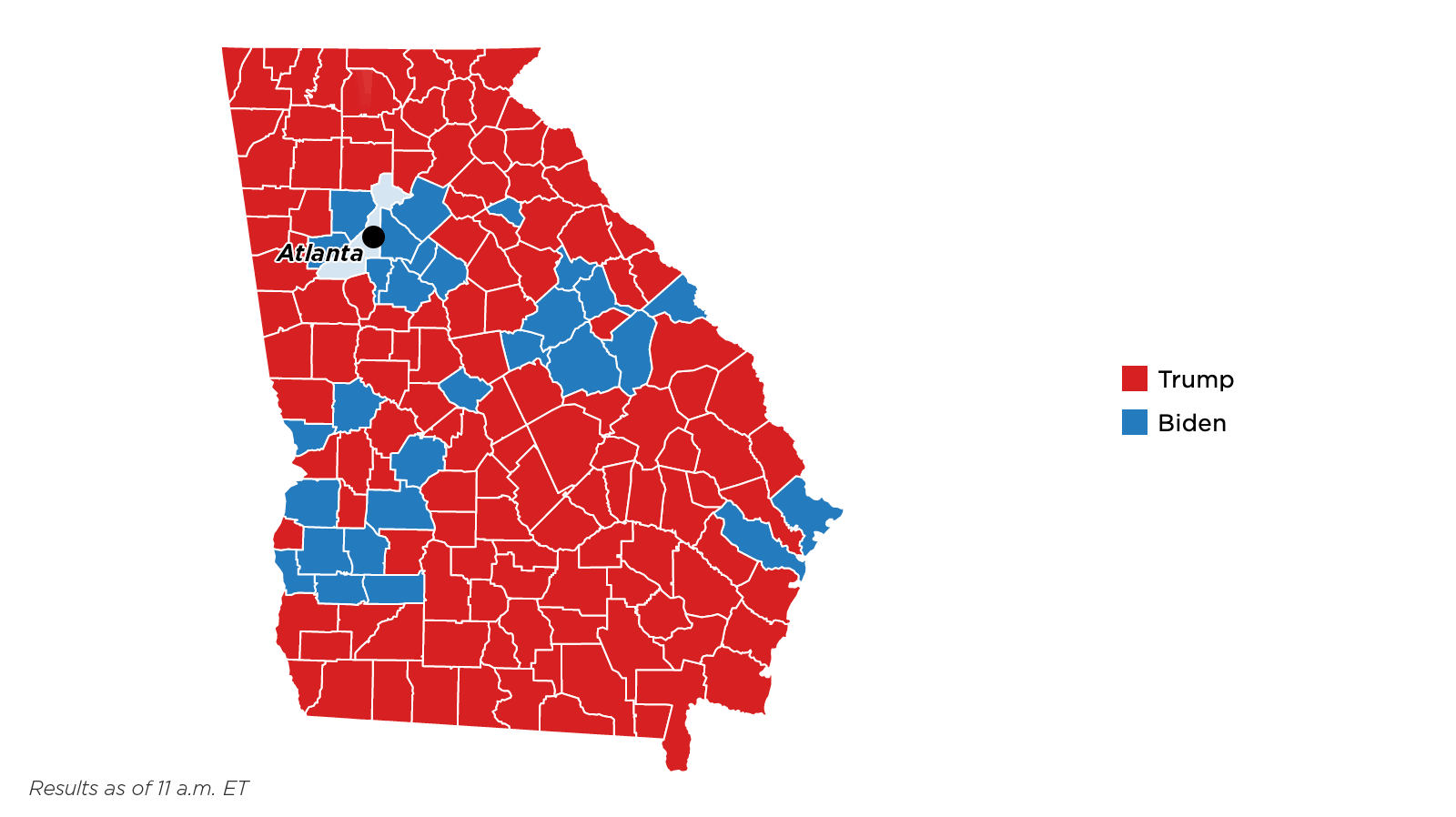

Georgia’s criminal justice system has taken the first step in criminal justice reform and helped contribute to true change in criminal justice in the United States. In the Georgia gubernatorial race in November of 2018, the candidates each has their own plans to impact the future of criminal justice in Georgia.

Stacy Abrams has made criminal justice reform a critical campaign promise. She served on Georgia’s Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform and helped pass many of the changes mentioned above. Her “Justice for Georgia”plan hopes to further reforms by focusing on the decriminalization of poverty, re-entry and transition program expansion, juvenile justice reform, and effective community policing, all in hopes of “improving jail court, and prison systems, lowering incarceration rates, reducing recidivism, aiding law enforcement, and making our communities safer by building trust throughout Georgia.”

Brian Kemp has a different approach to criminal justice. He claims that because of his experience and work with law enforcement and sheriffs in the court house, he has a more accurate viewpoint on the issue of criminal justice, which has inspired his approach of bringing back traditional law-and-order politics. This can be seen in two of his proposed policies regarding illegal immigration and criminal activity. Kemp’s “Track and Deport” plan will attempt to create a new criminal alien database that will assist law enforcement officers to deport criminal aliens. Along with combating illegal immigration, Kemp also plans to “Stop and Dismantle”gang activity in Georgia. This plan will empower the attorney general’s office to prosecute gang-related cases, create a gang strike team, and launch awareness campaigns against gang activity.This approach towards criminal justice reform reflects Georgia’s similar policy response to the national fear of crime that existed in the 1990s and 2000s.

While there are negatives in both candidates proposed plans, Brian Kemp’s “Stop and Dismantle” plan would be very costly for the state and the taxpayer and historically has not produced a definitive change on crime and recidivism rates. Abrams’ plan, however, would require very proactive and extensive post-conviction programs, which could be difficult to enforce long term.

Governor Deal has expressed hope that whoever wins the governorship will continue on the path towards reforming the criminal justice system by keeping the Criminal Justice Council and potentially reducing or ending mandatory minimum sentences. Hopefully, regardless of who wins the governorship in November of 2018, Georgians will remember the history of incarceration in Georgia and continue to allow the state to serve as a positive example of criminal justice reform for the rest of the country.