EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 Magazine.

In what world should a contestant’s ability to make an entree containing beef tendon, purslane, Jerusalem artichokes, and Reese’s cups determine if they can afford to keep paying their mother’s medical bills? And why do millions of Americans feel compelled to watch this situation play out on TV every week?

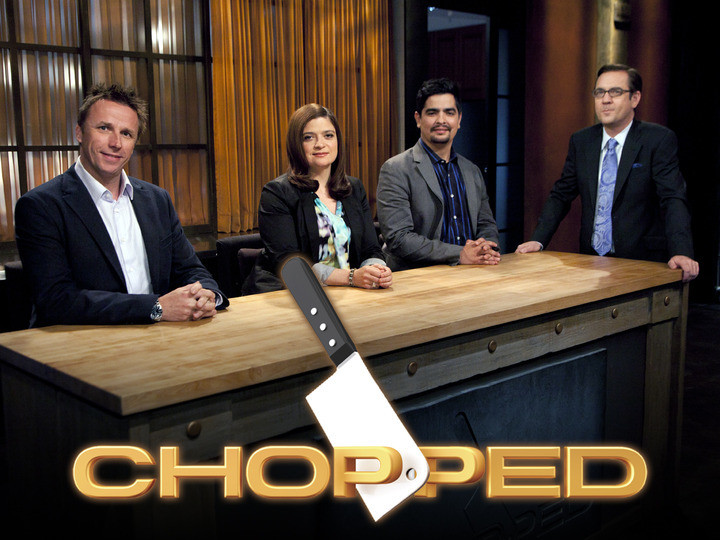

Chopped is an American television series and cooking game-show on Food Network. Every episode pits four chefs against each other in a multi-round contest. In each round, the chefs create a dish from a mystery basket containing four ingredients, notorious for their obscurity and utter inconsistency with the stage of the meal (ex. gummy bears in the entree round, chicken skins in dessert). The winner receives $10,000.

Each episode begins with a video montage of the participating chefs. Usually, this includes a statement on the respective chef’s current position and restaurant, a glib line of pseudo-competitive game-show maxim (“I didn’t come here to make friends–I came to win!”) and a brief explanation of what they would do with the money. The sob stories obviously have no bearing on the result. The Chopped gods do not care about why contestants need (or don’t need) the money. The Chopped gods are only concerned with sustained perfection.

The program has received critical acclaim and is widely considered one of the best cooking competition shows. A Vice review describes the program as “straight up” and “simply about the food.” But what’s the appeal of a food show that’s stripped of its humanity?

It’s been proven that the political and cultural climate can determine television viewing habits. A 2010 study by media-research company Experian Simmons found that there was no overlap between the top fifteen shows watched by Democrats and Republicans that year. If political orientation is represented by television viewership, then perhaps the absurdity of Chopped can be explained by a political phenomenon in our country– namely, the current economic condition of many young adults in the workforce.

Shifting economic conditions is partly tied to the increasing prevalence of the gig economy. A 2018 paper by Uttam Bajwa of the University of Toronto investigating global worker health defines the gig economy as connecting “consumers with contractors (or workers) through online platform businesses to perform tasks.” Bajwa challenges the gig economy’s benefit to worker health, citing “information asymmetry” and a “culture of surveillance” as harmful.

Visually, Chopped shares imagery with the gig economy and freelance work: small spaces, strict deadlines, workplace injury (via a sharp knife or mandolin), cheap processed food, and omnipresent stress. More deeply, the program reflects many fundamental issues of the gig economy. Chopped is famous for putting food before chefs, literally placing product before workers. The scene in which judges taste and critique the contestants’ food echoes Bajwa’s discussion of vulnerabilities of the gig economy almost point for point: judges reviewing the chef’s food behind closed doors, the constant assessment of the chef’s output, and using said assessment as the rationale for termination. If the gig economy is not committed to workers, then neither is Chopped or the motivations of its viewers.

We’ve discussed the implicit mapping from the real world to Chopped, but what about how Chopped defines its own relationship with the outside world? A spot on Chopped is itself a gig. So how does Chopped take into account the needs and concerns of its contestants? It doesn’t. Contestants present entirely different reasons for needing money – visiting one’s grandmother in Italy, donating it to a children’s charity, or buying a boat – but obviously Chopped doesn’t factor this into the results.

All this seems reminiscent of a recent story of a pregnant Lyft driver who drove customers in the midst of her own contractions. Lyft had the zeal to post this story on their company’s blog, oblivious to the irony of an employee forced to drive at nine-months pregnant while having no health-care or maternity leave from her employer. With the advent of the gig economy, we see a parallel trend of the compartmentalization of individuals. In all realms today, be it employment or academics or food television, individual identity is tied to output.

Not all food media must submit to this ideology. Reflecting on Anthony Bourdain’s career as a journalist, food was presented as an extension of culture, a pathway to understanding the whole. Bourdain’s first work Kitchen Confidential even discussed the unfair treatment of food-industry and service workers. Bourdain provided a necessary voice of dissent within food media. Chopped surrenders to the weight of modernity and corporate ideology.

All of this comes down to the question of meritocracy. We feel that it’s important to reward individuals according to the quality of their work. But at what cost? Should we really strive for accuracy over equity? Derision over dignity? Efficiency over understanding?

Why should we want to be the Chopped gods?

___________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/wj8q39/how-chopped-became-tvs-greatest-cooking-show

https://psmag.com/social-justice/television-reinforces-politics-74128

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6299501/

https://gizmodo.com/lyft-thinks-its-exciting-that-a-driver-was-working-whil-1786970298