How Australia is Circumventing the UN Refugee Convention

By: Eli Scott

“We don’t want Indonesia to be a dumping ground, but we don’t want Australia to accuse us of not doing anything,” claimed Djoko Suyanto, an Indonesian spokesperson, on Nov. 8, in response to a recent standoff between Australia and Indonesia.

Australian authorities responded to the distress call of a wooden boat containing around 60 people, presumably from Indonesia, off the coast of Java on Thursday, and Australian officials were trying to convince Indonesia to take these refugees. However, Indonesian officials maintained that Australia had its own detention centers to which it could send such refugees. Thus, Australian Minister for Immigration and Border Protection Scott Morrison has decided to “transfer the persons rescued…to Christmas Island.” This bilateral fiasco illustrates the larger problem of how Australian politicians and media are fueling nativism against refugees in order to circumvent Australia’s outstanding obligations to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The term “White Australia” refers to Australian immigration policy that favored immigration from European countries and peoples of European descent. “White Australia”-influenced policy began in the 1850s when Chinese immigration was restricted on the account of the xenophobic resentment of Australian miners in the Victoria province. According to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, the “White Australia” policy was abolished in 1966 and steps have been taken to liberalize the immigration process for non-Europeans. Although the old policy has been nominally denounced, Australia is still following discriminatory practices that breach UNHCR obligations due to the inordinate amount of focus placed on immigration by prominent politicians.

Australia ranks second on the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) list of countries with the highest percentage of population consisting of immigrants; 26.5 percent of its population is born overseas. This statistic is more than double that of the United States, a country claiming to be a melting pot of diversity. The immigration statistics of these two countries, though, differ significantly in the composition of immigrants. “More than half of Australia’s foreign-born population comes from an English-speaking country” with most immigrating from the United Kingdom and New Zealand. By contrast, a mere five percent of the United States’ immigrant population comes from English-speaking countries. According to James Raymer, a professor of demography at the Australian National University, this difference stems from contrasting policies such that “Australia…gives preferences to language and skills whereas the U.S. gives preference to family relations.” Hence, Australia, although seeming pluralist in its immigration policies, maintains open legislation primarily toward residents of English-speaking countries.

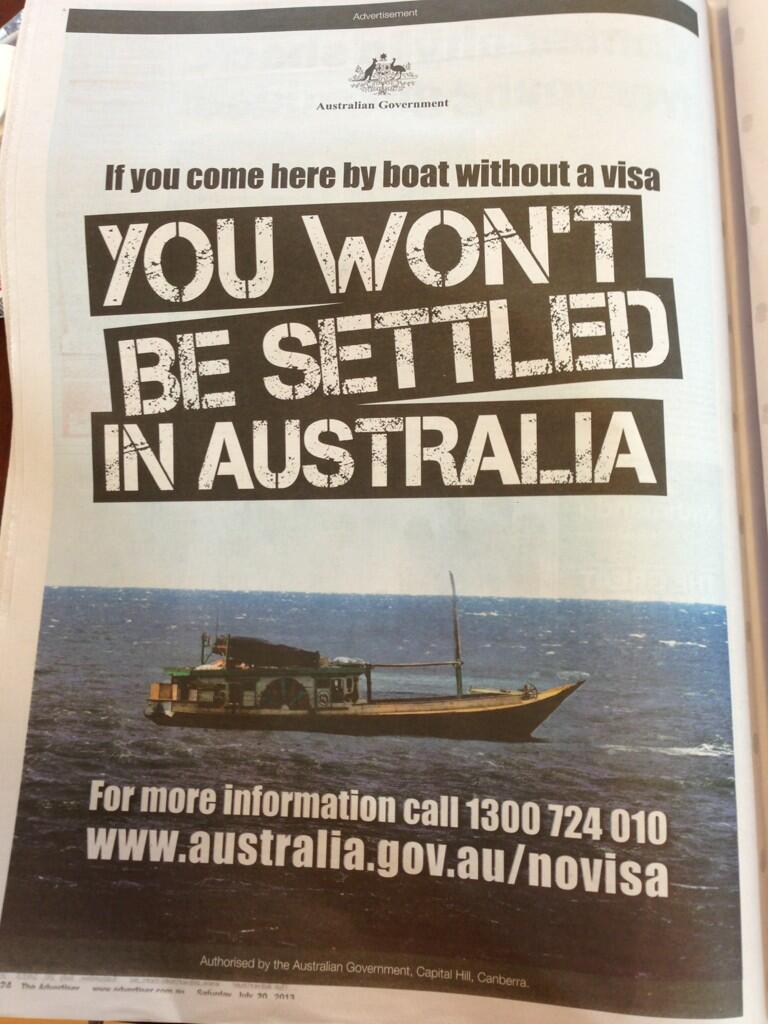

As a signatory of the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, Australia is obligated to grant refugees asylum. Nonetheless, Australia currently circumvents this obligation by sending rightful asylum seekers to detention centers on Christmas Island and, thanks to a political deal involving foreign aid with Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Peter O’ Neill, to Manus Island. According to the Regional Resettlement Arrangement, “any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees.” The Regional Resettlement Arrangement inevitably concerns the UNHCR, which has claimed that Papua New Guinea lacks the legal infrastructure and prowess to effectively handle the demands of processing refugees.

When Australia’s new Prime Minister Tony Abbott of the Liberal/National coalition was elected in September, he affirmed that he would continue the policy of sending boatpeople, refugees that travel by sea, to Papua New Guinea as maintained by the Labor Party. Abbott initiated Operation Sovereign Borders, a military-led crackdown on human traffickers. Australia, because of its proximity to the island nations of Asia, experiences difficulty accommodating asylum seekers that come by boat from Indonesia as well as other Asian countries. Under the reins of newly elected Abbott, the Australian Immigration Minister Scott Morrison has attempted to use politically charged jargon to dehumanize asylum seekers by having his staff and department workers refer to them as “illegals” and “detainees.”

As the result of political scapegoating by government officials and excessive media attention, over half of the Australian public deems the issue of boatpeople as or more important than issues of managing the economy, promoting education, and providing healthcare services. Many Australians view these boatpeople as illegitimate asylum seekers that are trying to inundate the mainland. These views are propagated by politicians such as Abbot who claim that the mainland is currently undergoing a “border protection crisis.” In reality, in the years 2011-2012, 93 percent of people arriving via boat were legitimate refugees according to the refugee convention. Moreover, only 2.7 percent of all migrants to Australia are asylum-seeking boatpeople.

The recent standoff between Indonesia and Australia concerning asylum seekers has been useful in exposing the duplicitous nature of Australian immigration policy: refugees cannot seek asylum in Australia due to its deals with Christmas Island and Papua New Guinea. In order to more fully and transparently uphold the UN Refugee Convention, Australia should nullify its Regional Resettlement Arrangement and allow refugees to enter its borders and rightfully seek asylum.