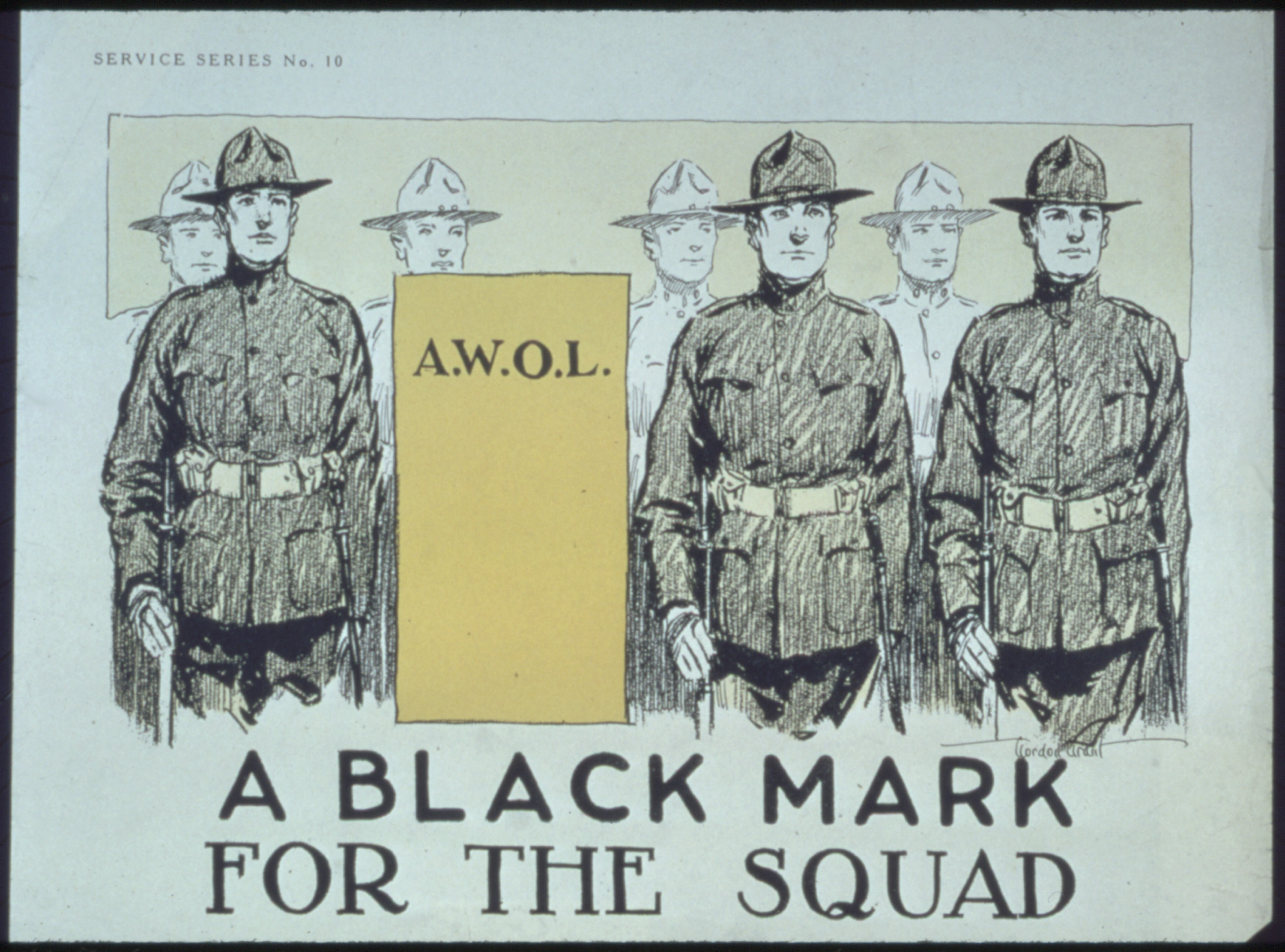

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

By: Michael Land

“Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom … to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

– Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18

In 1976, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, entered into force. In 1993, the UN Human Rights Committee explicitly clarified article 18: “The Covenant does not explicitly refer to a right to conscientious objection, but the Committee believes that such a right can be derived from article 18, inasmuch as the obligation to use lethal force may seriously conflict with the freedom of conscience and the right to manifest one’s religion or belief.”

Though the United States signed the Covenant, the stipulations attached by Congress have rendered it ineffective. The Human Rights Committee has stated that “[T]here is an absence of provisions to ensure that Covenant rights may be sued on in domestic courts, and, further, a failure to allow individual complaints to be brought to the Committee… [A]ll the essential elements of the Covenant guarantees have been removed.” Today, though the United States recognizes the right to become a conscientious objector (CO), there are many barriers to obtaining this status. It is prudent to question whether or not these limitations serve any purpose, and if the government should have the ability to subjectively discriminate between certain types of ethical objections.

Many religions have advocated for pacifism or a rejection of military service. Early Christian theologian Hippolytus of Rome (170-275 CE) stated, “If a believer seeks to become a soldier, [he] must be rejected, for [he] has despised God.” Historically, members of the Church of the Brethren, Quakers, and Mennonites have refused military service; these denominations are collectively known as the peace churches. Nonviolence is central to Jainism, and many groups within Hinduism and Buddhism also advocate pacifism. Additionally, organizations such as Peace Brigades International and War Resistors’International work to promote pacifism and anti-militarism from a secular perspective.

Despite the numerous organizations that advocate nonviolence, the right to conscientious objection from military service has not always been recognized in the United States. There were plans to institute a draft as early in America’s history as the War of 1812. In a speech before the House of Representatives, Daniel Webster made the following statement:

“Where is it written in the Constitution, in what article or section is it contained, that you may take children from their parents, and parents from their children, and compel them to fight the battles of any war, in which the folly or the wickedness of government may engage it? Under what concealment has this power lain hidden, which now for the first time comes forth, with a tremendous and baleful aspect, to trample down and destroy the dearest rights of personal liberty?”

The first national conscription in the United States occurred during the Civil War. Though conscientious objector status was not part of the draft law, soldiers could pay a $300 fee to avoid military service. This enormous sum was affordable for wealthy citizens, and those who could not afford to pay had few options. Those who could not (or chose not to) avoid conscription were forced into military service and subjected to deplorable conditions.

During World War I, a religious right to conscientious objection was recognized, and COs were permitted to serve in noncombat roles. For some objectors, however, no association with the military was acceptable. Roughly 2,000 civilians who refused to participate in the war in any fashion were incarcerated in military prisons. They were subjected to short rations, solitary confinement, and harsh treatment; some objectors did not survive their prison sentence.

In 1965, the Supreme Court ruled that a valid claim of conscientious objection could be based on a moral belief, as long as it was “a sincere and meaningful belief occupying in the life of its possessor a place parallel to that filled by the God of those admittedly qualified for the exemption.” However, the Court also found that “the exemption does not cover those who oppose war from a merely personal moral code.” In 1971, the Supreme Court found that a conscientious objector must object to all wars in order to avoid military service, and cannot object to specific wars on the grounds of conscience.

Currently, the military maintains that it is comprised only of volunteers. In the United States, at least, it is true that there is no conscription or military service requirement in place. Unfortunately, a soldier faces immense difficulties if he decides to leave the military before his term of service expires. Though a soldier may receive a discharge due to hardship or dependency, these circumstances are beyond his personal control. A dishonorable discharge may only be handed down by a court martial. The social stigma attached to a dishonorable discharge makes it difficult to obtain meaningful employment after a soldier leaves the military. In most cases, a person who receives a dishonorable discharge will also lose the right to vote or receive governmental assistance of any kind. These penalties are more than sufficient to discourage desertion, and conscientious objectors will almost always follow official channels in order to leave the military in good standing.

In 2013, Private Chris Munoz refused to deploy to Afghanistan along with the rest of his unit. In a statement, Mr. Munoz’s lawyer explained why his client was seeking conscientious objector status. “At weapons training, he really began to think about what he was being asked to do. He was told there could come a situation where he might be forced to fire on a child. He realized then he could not fire upon a child, even if that child was a risk to him… That’s when things really clicked for him.” According to Mr. Munoz, he was repeatedly told by his superiors to delay his application for CO status, even though his deployment was approaching. Originally, Munoz was told that he would have to deploy while the Army deliberated on his case. However, after Munoz and his attorney contacted the press, the military felt forced to allow him to remain in the United States. Munoz has faced criticism from many service members, including accusations that he is “not a real CO” and that he is abandoning his brothers-in-arms.

Unfortunately, Chris Munoz’s case is not unique. An application may take months to process, and is subject to multiple denials and appeals. And until the case is closed, a CO must continue his military service. Michael Izbicki tells the story of how he came to join the military and then developed moral objections to service. The Navy denied his application twice, and it took a court fight and representation by the American Civil Liberties Union in order for Izbicki to be discharged as a CO.

It is a double standard that a civilian employee may walk away from his job for any reason, but a soldier must fight through the court system in order to secure his personal liberty. At what point may the government override a person’s sincere desire to leave military service? If a person is denied the opportunity to leave their job in the military, then what is the difference between military service and indentured servitude?

Those who do not support a right to conscientious objection might opine that a soldier has voluntarily signed a contract to perform military service and is thus obligated to fulfill the terms of that contract. Such reasoning is overly simplistic; we do not allow people to contractually sell themselves into slavery, so there must be some limit on how people’s past agreements can affect their current decisions. If a 17-year-old signs a contract promising eight years of military service, must we deny him the right to change his mind until he turns 25?

In his book “It’s a Jetsons World,” Jeffrey Tucker of the Mises Institute explores the contrast between a truly voluntary military and the current system: “Yes, there are contracts, but the military can void them whenever it so desires. Predictably, it desires to void those contracts (through so-called stop-loss regulations) when the enlisted most want to leave: when they must kill and risk being killed… If [modern presidents] constantly faced the prospect of mass desertions, they might be more careful about getting involved in unnecessary, unjust, and unwinnable wars, or going to war at all. Peace would take on new value out of necessity.”

The cries to “support our troops” and the machinations of war-hawk politicians have led many Americans to believe that military service is desirable and honorable for all citizens. Many soldiers have no ethical reservations about serving their country, but is it justifiable to punish those who do? It is the responsibility of the American government to provide information about conscientious objector status to soldiers, as well as a viable exit option for any soldier who has developed a moral aversion to military service. Regardless of the military’s attitude towards those who join their ranks and then decide to leave, keeping an unwilling soldier captive to a job is tantamount to slavery. In the words of John F. Kennedy, “War will exist until that distant day when the conscientious objector enjoys the same reputation and prestige that the warrior does today.”