By Bhanodai Pippala

The death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has led to a confirmation battle over Merrick Garland, who was appointed by President Barack Obama in March 2016 to replace Scalia on the bench. The Senate has yet to vote on the confirmation of Garland or hold hearings under the Senate Judiciary Committee. The potential appointment of Garland could be monumental as it could shift the ideology of the Supreme Court leftward, since there would be five liberal justices and four conservative justices. It would be the first time since 1969 with the retirement of Chief Justice Earl Warren that the United States has seen a liberal leaning Court. The United States could see the abolishment of the death penalty with the appointment of Garland and the rise of a liberal Supreme Court.

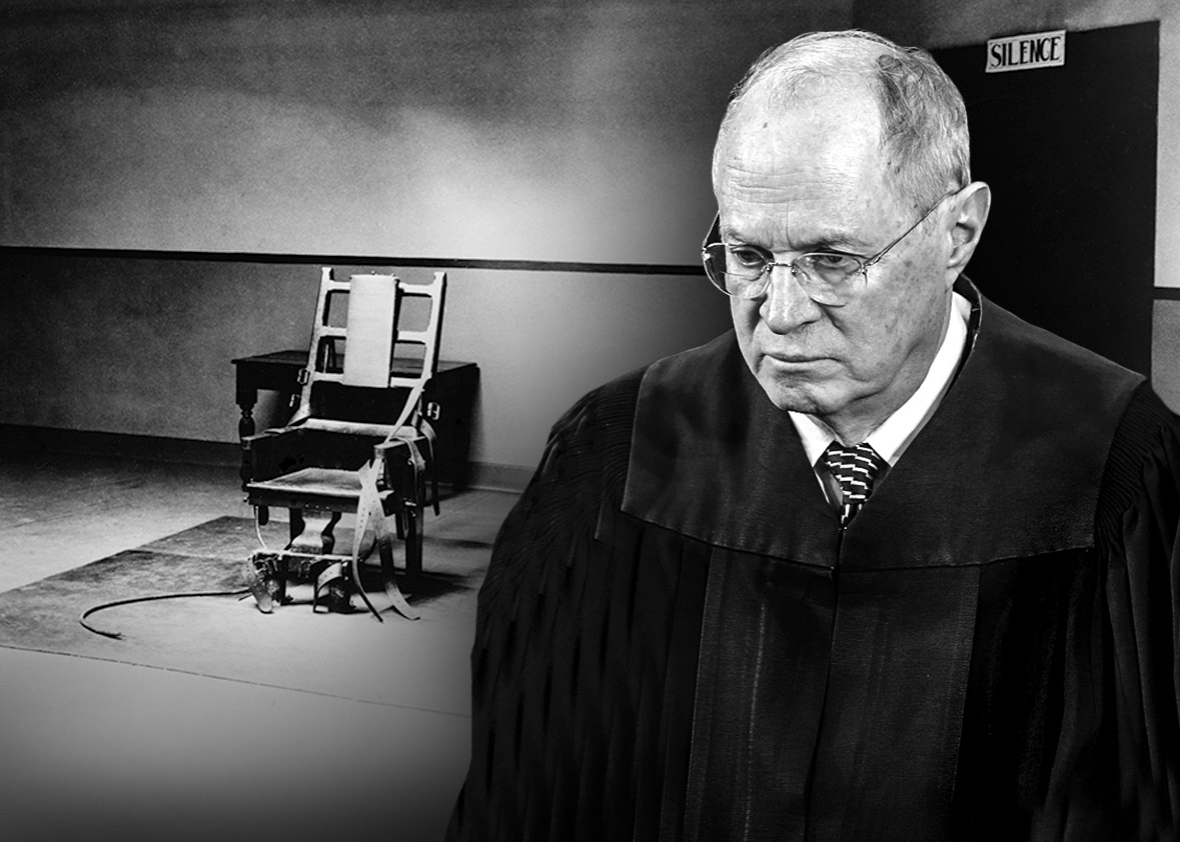

In June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Hector Ayala, an inmate who has been on California’s death row for 25 years, in a case over whether a prosecutor could dismiss members of a jury pool without Ayala’s lawyer bring present. The Court ruled that the exclusion of Ayala’s lawyer only constituted a “harmless error,” but most of the attention surrounds Anthony Kennedy’s concurring opinion on Ayala’s treatment while on death row.

Justice Kennedy harbored strong feelings against the use of solitary confinement for Mr. Ayala. As Kennedy described in his opinion, Mr. Ayala “has been held for all or most of the past 20 years or more in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day; and in the one hour when he leaves it, he likely is allowed little or no opportunity for conversation or interaction with anyone.” Kennedy’s opposition to solitary confinement, even as a leaning conservative, hints to progressive decisions regarding higher profile issues such as the death penalty. As more liberals such as Garland are appointed to replace conservatives such as Antonin Scalia, the Court’s median ideology will shift further left. As a result, a liberal leaning court may be more willing to not only rule solitary confinement unconstitutional but also the institution of the death penalty.

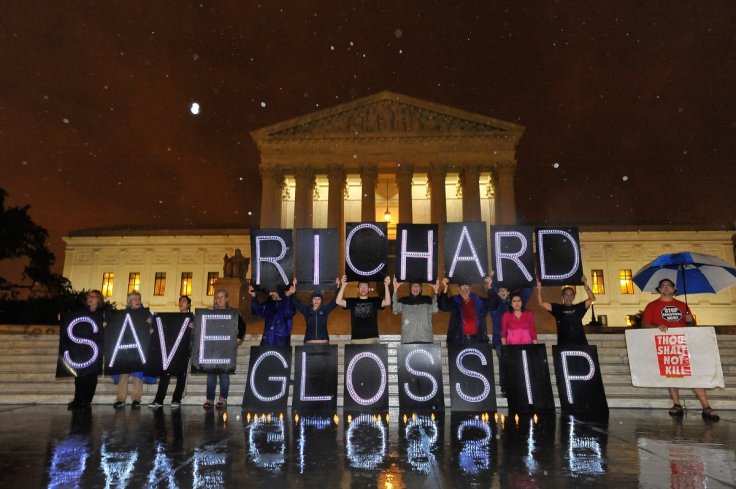

Decisions by the Supreme Court regarding the death penalty have seen a variety of harsh dissents by some justices such as Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. These two justices argue that the practice is unconstitutional, as indicated in the 2015 case Glossip v. Gross. The case dealt with the use of the drug Midazolam, which was also use in the botched execution of Clayton Lockett; Lockett eventually died of a heart attack. The Court, divided by a 5-4 opinion, ruled that the use of Midazolam didn’t violate the Eight Amendment protection against “cruel and unusual punishment.” Justice Breyer wrote a dissent that was joined by Justice Ginsberg, which advocated for the abolishment of the death penalty. If the Court were joined by liberal leaning justices in the next ten years, Breyer’s dissenting opinion could very well become the majority.

In the 1972 case Furman v. Georgia, the Court effectively halted the use of the death penalty on grounds that states handed down the punishment arbitrarily. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the death sentence itself was not unconstitutional, but the arbitrary nature in which states were ruling for the death penalty often violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Even though the five justices in the majority agreed that the death penalty should be halted because it was unconstitutional, each had a different opinion as to why this was the case. The Furman decision effectively stopped the use of the death penalty across the nation by invalidating state statutes without declaring the death penalty unconstitutional in principle.

States responded to the Furman case by drafting new statutes to relieve fears that the death penalty was being handed down arbitrarily. The 1976 case Gregg v. Georgia saw the Court deal with the constitutionality of a bifurcated trial procedure in deciding whether to sentence an individual to the death penalty. In a bifurcated trial, an individual is first declared guilty or not guilty by a jury. Then, a jury decides in a separate trial whether the person is given the death penalty or life in prison. The Supreme Court upheld the bifurcated trial procedure and effectively ended the national moratorium on the death penalty.

Within the past two decades, the Supreme Court has instituted major limits to the death penalty. In Atkins v. Virginia, the Court ruled that the mentally challenged could not be executed. In Roper v. Simmons, the Court ruled that the death penalty could not be applied to minors under the age of eighteen. Kennedy v. Louisiana saw a further restriction to the applicability of the death penalty by affirming that it could only be applied for crimes which led to the death of a victim, with exceptions of treason and espionage. Even with the restrictions, the Court has upheld multiple procedures dealing with the death penalty, including lethal injection in the case Baze v. Rees. Thus, through cases such as Baze, the Supreme Court has reaffirmed that the practice itself is constitutional.

This year’s presidential election affects not only the next four (or eight) years but could potentially shape the future of the Supreme Court. The Court could continue to follow a conservative track or a may pave a revived liberal course last seen under Earl Warren. If the Court does track leftward, it could lead to many progressive decisions, including ruling the death penalty unconstitutional under a strong coalition.