By Ariel Pinsky

“Sometimes people ask me, ‘What is the greatest achievement you have reached in your lifetime or that you will reach in the future?’ So I reply that there was a great painter named Mordecai Ardon, who was asked which picture was the most beautiful he had ever painted. Ardon replied, ‘The picture I will paint tomorrow.’ That is also my answer.” – Shimon Peres, former President of Israel

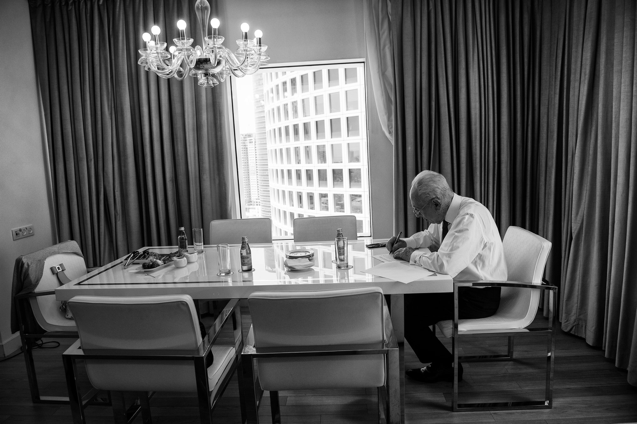

As a nation mourns the loss of Shimon Peres, a beloved leader and one of Israel’s last remaining founding fathers, his words take on a new meaning. Peace is the picture Peres had long dreamt of painting and the mission to which he devoted his life’s work. Unfortunately, “tomorrow” never did come soon enough—Peres passed away on Wednesday, September 28 at 93 years old in a Tel-Aviv hospital.

Over 75 foreign delegations gathered to commemorate the life and vision of Peres at Mount Herzl, Israel’s national cemetery in Jerusalem. The cemetery is named after Theodore Herzl, the 19th century scholar and father of Zionism who envisioned the very same Jewish state that Peres and his contemporaries would eventually pioneer.

Throughout his political career, Peres served as prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, and then president until 2014, never once leaving the spotlight since Israel’s birth in 1948. When he left his post in 2014, Peres was the oldest head of state of any nation.

President Obama, who knew Peres personally, delivered a eulogy at the ceremony in Jerusalem alongside international leaders such as former President Bill Clinton, President François Hollande of France, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada, President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico, and King Felipe VI of Spain. President of the Palestinian Authority Mahmoud Abbas was also in attendance despite criticism from both Israelis and Palestinians.

Obama began his speech by being the only speaker to recognize the attendance of Abbas, calling it “a gesture and a reminder of the unfinished business of peace.”

Obama went on to classify Peres as one of the “giants of the 20th century” whom he’s had the honor of meeting, from Nelson Mandela to Queen Elizabeth. He described Peres as one of the “leaders who have seen so much, whose lives span such momentous epics that they find no need to posture, or traffic in what’s popular in the moment, people who speak with depth and knowledge, not in sound bites.”

Obama might have been alluding to the fact that Peres was unpopular with segments of the Israeli public for several “moments” in history that defined his political career and contributed to his intricate legacy. Peres was not always the universally-adored public figure he became when assuming the ceremonial role of president in 2007. Ironically, what Peres considers to be one of his proudest accomplishments was also the source of much of the controversy and animosity directed toward him as foreign minister.

In 1993, Peres hammered out a plan after months of secret negotiations with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) for self-government in Gaza and in part of the West Bank, territories Israel had recaptured during the 1967 Six-Day War, also known as the Arab-Israeli War. Peres managed to convince his old political rival and prime minister at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, to proceed with the diplomatic breakthrough that became known as the Oslo Accords.

The agreement called for Israeli troops to withdraw in stages from the West Bank and Gaza and created the Palestinian Authority, which allowed for limited self-governance over those territories. Though the deal did not result in peace or an eventual Palestinian state, it implied that both sides were willing to acknowledge their mutual political and territorial rights for the first time since Israel’s creation.

PLO chairman Yasir Arafat and Prime Minister Rabin officially signed the deal on September 13, 1993 at the White House with the wholehearted support of then-President Bill Clinton. The plan broke an almost 50-year impasse characterized by a lack of direct negotiations between the Israeli and Palestinian leadership.

“What we are doing today is more than signing an agreement; it is a revolution,” Peres proudly asserted that day. “Yesterday a dream, today a commitment.” Peres, Rabin and Arafat were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize one year later in 1994 for their efforts at reconciliation through this landmark deal. The decorated leader also received the French Legion of Honor in 1957 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012 for his peace efforts.

Though the Oslo Accords were generally well-received by the international community at the time, critics at home accused Peres of being weak and too eager to replace military action with naïve diplomacy, accusations that had begun during his years as prime minister during crises like the 1976 Air France hijacking.

Prominent Israeli politician and former foreign minister Tzipi Livni recently wrote in an op-ed in the New York Times, “When fellow Israelis called him a traitor and screamed ‘Oslo criminal’, it hurt him. We could all see it in his eyes; he wanted to be loved — but he was not willing to give up on his beliefs.”

Peres’s critics struck from the right and the left, the religious and the secular.

As the right criticized him for his reluctance to take military action and sheepishness in the face of crises, the left berated him for endorsing the construction of settlements and for launching military strikes that inadvertently led to civilian deaths.

Peres was considered a “security hawk” for building up Israel’s military capacity and developing its nuclear program, which now serves as the basis for Israel’s leverage when negotiating with other nations. Peres arranged for a $1 billion arms deal with the French and is largely responsible for the nuclear reactor that now sits in the Negev Desert. Since then, Israel’s strongest ally and supplier of military technology has been the United States.

However, there is reason to believe that Peres was not truly a “hidden hawk,” but rather the peacemaker that characterized his later image: The Jerusalem Post recently revealed that Peres had confidentially told the paper two years ago that he “personally intervened to stop Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from ordering a preemptive strike on Iran’s nuclear sites.” According to the Post, Peres said that they could publish this information upon his death.

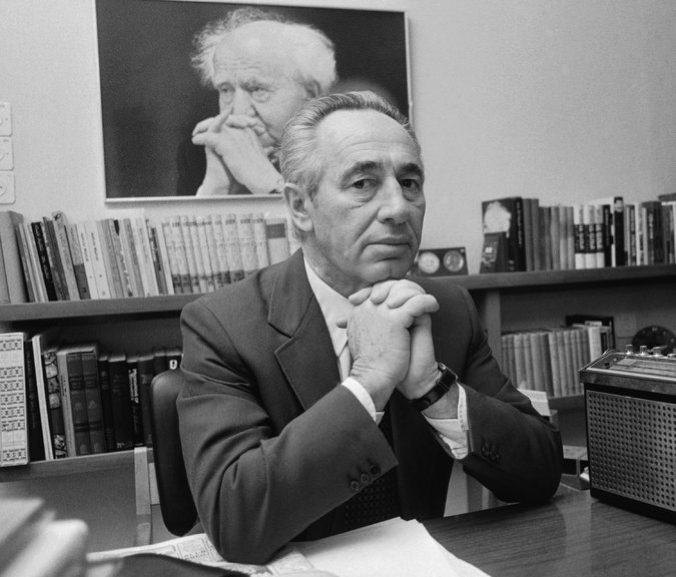

Two things his supporters and critics tend to agree on are Peres’ charisma and impressive personal qualities. Peres was a commanding speaker with an exuberant personality who made it a point to garner close, personal relationships with party members and staffers. Peres, who was born in a shtetl (small village) in Poland, never lost his Polish accent, but spoke six languages by the end of his life: Polish, French, English, Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew. He published 12 books and was a fervent lover of literature, poetry and history — his contemporaries say he frequently quoted from the Hebrew book of prophets, French and English literature, and ancient Chinese philosophy.

Peres will likely remain iconic in the eyes of Israelis for promoting the country’s high-tech industry and cultural development, transforming Israel’s economy by tackling Israel’s underlying economic problems and rising inflation, and for being the architect of Israel’s nuclear program and sophisticated weaponry, arguably the most important aspect of Israel’s modern national security.

Though in the end Peres was unable to accomplish the large-scale picture of peace he had so obstinately sought, he was able to paint smaller pictures throughout his political career, from establishing the Peres Center for Peace in 1996 to airlifting nearly 7,000 Ethiopian Jewish refugees to Israel escaping famine, anti-Semitism, and warfare. Though the image of a benevolent and romantic dreamer will be seared into Israel’s collective memory for many generations to come, Peres should also be remembered for being a true fighter; Peres did more than merely dream — he fought for Israel’s independence, its security, and then, for its peace.