Is It Alive and Well, In the Process of Dying, Or Dead?

Is It Alive and Well, In the Process of Dying, Or Dead?

By: Sarah Smith and Megan White

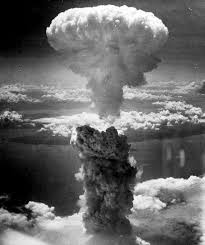

On Aug. 6, 1945, the traditional fabric of war and security that had held the international system together for centuries was incinerated. That morning, an American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, carried out world’s first atomic attack on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a second atomic attack leveled Nagasaki. The results were devastating: more than 100,000 people were killed instantly, and the final death toll from the two attacks reached at least 185,000. Thousands were left homeless, and the cities continue to suffer from the residual effects of radiation. Resonating far beyond the shores of Japan, the two bombs unleashed a new era of uncertainty, fear, and multilateral diplomacy.

The unprecedented power of this new weapon demanded an unprecedented response from the international community. In 1968, 62 countries signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). At the time, multilateral agreements regulating particular methods of warfare were nothing new: as early as 1675, the Strasbourg Agreement between France and the Holy Roman Empire prohibited the use of poison bullets, and, more recently, the 1925 Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical and biological weapons. What set the NPT apart was the scope of what it sought to control. Atomic energy has the potential to power the world, as well as the potential to destroy it, a fact the international community does not take lightly. With 189 state-parties as of 2013, the NPT is the most widely accepted arms control agreement to date.

The cornerstone of the global non-proliferation regime, the NPT establishes a legally binding framework whose foundations rest on three principals: (1) states without nuclear weapons as of 1967 may not acquire them; (2) the five states known to have tested nuclear weapons prior to 1967 may not assist other states in acquiring them and must agree to pursue disarmament; and (3) states without nuclear weapons are guaranteed access to civilian nuclear technology and energy development. The International Atomic Energy Agency serves as the implementing body for the NPT, ensuring that all signatories comply with the treaty and adhere to a system of safeguards through its ability to impose sanctions. Until recently, the regime remained firmly rooted in the international arena, withstanding the tension of the Cold War and the tumult of the post-Soviet world. Atomic energy has not been used in warfare since 1945, and in the 50 years since the treaty’s inception, only five states (three of which are not party to the NPT) have developed nuclear weapons programs.

Although it has seen a degree of success, the NPT has perhaps lived too many half-lives. The international political and technological landscapes have changed significantly since the treaty entered into force in 1970, but the legal regime has not kept pace. In essence, the NPT lacks a forceful mechanism against the very threat it was meant to prevent: the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Specifically, the treaty provides no culpability for violation, and even contains an article permitting withdrawal. Coupled with the IAEA’s limited budget and lack of adequate verification and enforcement mechanisms, the nonproliferation regime falls short of what is needed to detect, prevent, or punish weapons development.

Despite the NPT’s broad legal coverage, a series of failures since the early 1990s have highlighted its ineffectiveness in deterring would-be nuclear weapons states. This is perhaps most apparent in the decades-long struggle with North Korea and the more recent resurgence of Iran’s nuclear ambitions. At one point in time, both nations “adhered” to NPT protocol by allowing for limited IAEA safeguards and inspections. In 2003, however, North Korea formally announced its withdrawal from the NPT, while Iran shockingly remains party to the treaty. Since its withdrawal in 2003, North Korea has conducted nuclear tests in 2006, 2009, and 2013. Iran continues to rapidly enrich uranium, ostensibly for civilian nuclear energy, though a recent NASA report claims that Iran should have a nuclear weapons capability by 2015.

Significantly, of the nine countries that possess nuclear warheads, four (44 percent) are not currently party to the NPT. These include India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel, the existence of whose nuclear program remains a secret. One of these countries, Pakistan, was the source of a black market proliferation network under Abdul Qadeer Khan, a scientist who shared nuclear information and technology with North Korea, Libya, and Iran. The NPT’s inability to reign in proliferation, a problem with potentially worldwide implications, outside the confines of its list of signatures speaks volumes to its fragility.

In addition to the NPT’s shortcomings in the realm of nonproliferation, its ambiguous call for disarmament remains to be answered. Among the five nuclear weapons states recognized in the treaty, 22,000 warheads remain stockpiled. Though President Obama’s 2009 Prague speech and UN Resolution 1887, which call for accelerated efforts towards total nuclear disarmament, offer a glimmer of hope for the second pillar of NPT, their significance is symbolic rather than practical. Beneath the rosy veneer of reduction agreements, nuclear states are seeking refurbishment, rather than destruction, of their arsenals.

While the NPT takes a 21st century reality check, new policy ventures have plugged the holes in the non-proliferation dam. One such policy is UN Resolution 1540, a legally binding instrument requiring all UN member states to enact and enforce measures to prevent non-state actors from acquiring unconventional weaponry and means of delivery. The inconsistent implementation of the resolution, however, has taught the international community that a universal non-proliferation treaty might be an unrealistic hope. Instead, the major powers have begun to address emerging nuclear states and contentious regions on an individual basis.

One such instance is the 2008 U.S.-India 123 Agreement. The deal lifts a three-decade U.S. moratorium on nuclear trade with India, provides U.S. assistance to India’s civilian nuclear energy program, and permits India’s admission to the Nuclear Suppliers Group. In return, India has allowed for increased IAEA inspections with the stringent Additional Protocol and has agreed against diverting certain resources toward their militarized nuclear reactors. Though India’s nuclear program has fallen under a higher degree of control, the agreement essentially undercuts the NPT by allowing the program to exist and even thrive outside the global regime.

The jury is still out on what the U.S.-India 123 agreement means for the NPT, but it does nonetheless represent a new trend in dealing with today’s proliferation challenges. As demonstrated in the Six Party Talks with North Korea and P5+1 meeting with Iran, Libya’s abandoning its nuclear weapons program in 2003, and Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Ukraine’s move to relinquish their weapons following the collapse of the Soviet Union, nuclear diplomacy may require action on a country-to-country basis through ad hoc multilateral efforts, rather than the peddling of a one-size-fits-all policy. That’s not to say that there is no place for a global nonproliferation regime. These examples serve to showcase the maturity, and even the future, of non-proliferation policy. Although the reign of the NPT has perhaps come to an end, the treaty remains one of the most influential pieces of international policy to emerge from the 20th century. Its precedent of peaceful international cooperation to solve a problem with global ramifications has held as a buffer against Einstein’s vision of a future where wars are fought with sticks and stones.