By: Haley Barnes

On November 4th, 2017, runners lined up at the start line in Asheville, North Carolina to begin a 5k race. It was, however, no ordinary race—the route that the runners set out on went along the line between the 10th and 11th Congressional districts. Organized by the League of Women Voters, the race was meant to make people understand and feel the impact of gerrymandering by having them run along the obscure line that had been drawn to split the two districts. The line divided the left-leaning city into two districts; when these districts were combined with an array of conservative areas, both of the districts ended up represented by Republicans. This ‘Gerrymandering 5k’ shows that partisan gerrymandering quite literally runs elections.

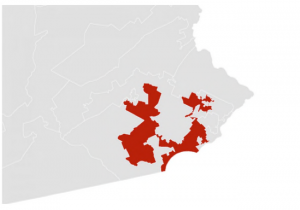

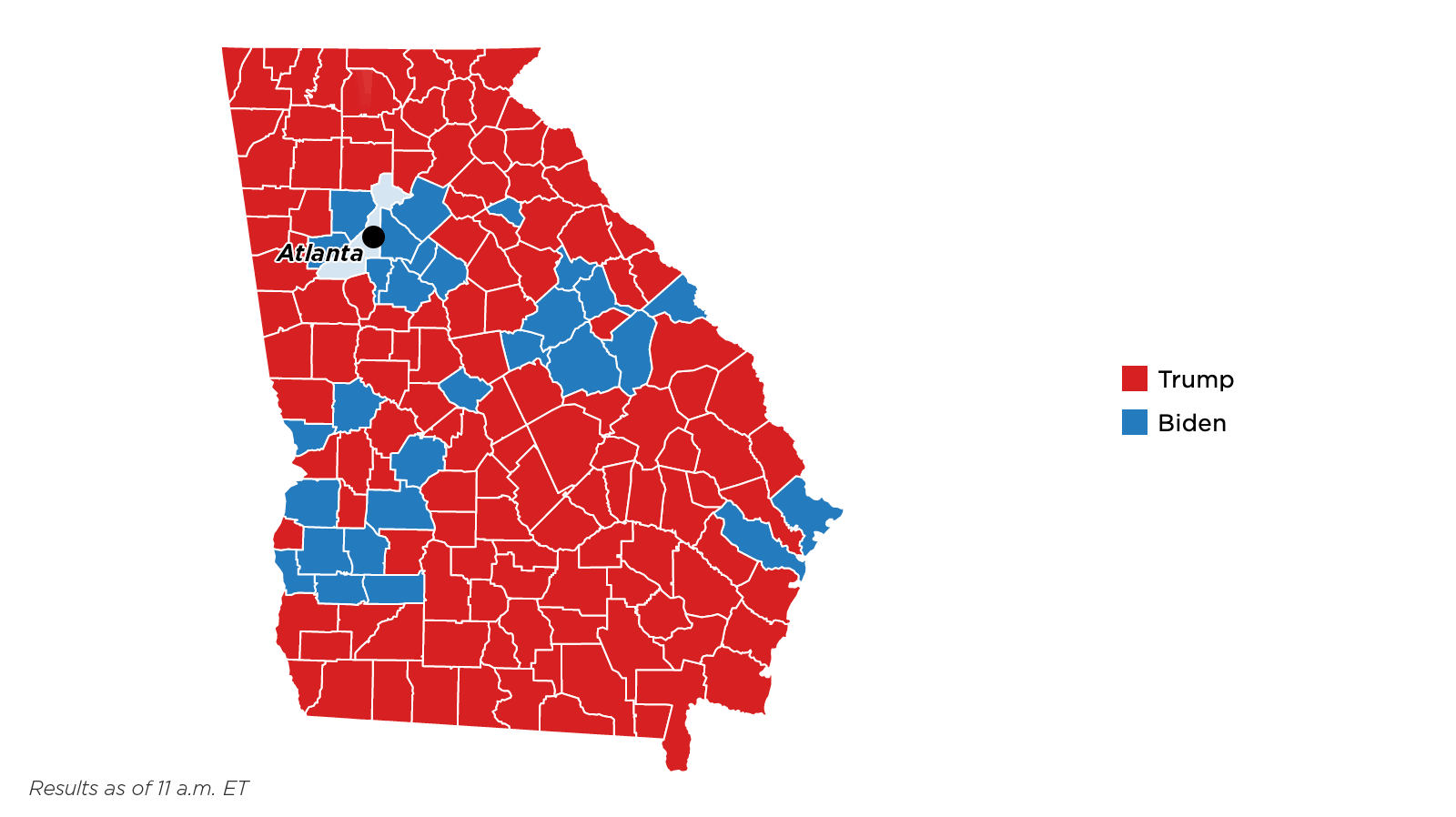

Across North Carolina’s Congressional districts, republicans won 53 percent of the vote, but ended up with 77 percent of state seats. North Carolina, however, is not the only case in which obscure voting district lines are drawn by officials to filter votes in such a way that the outcome of elections lean towards candidates of their own party. In Ohio, 40 percent of constituents voted Democrat, but 12 out of 16 of the districts ended up with Republican representatives. In Wisconsin, Republicans received less than 49 percent of the vote, but won 60 out of 99 state legislative seats. In Pennsylvania, Democrats won 51 percent of the popular vote in 2012, but received only 5 out of 18 seats in the House. These discrepancies are due to the seemingly nonsensical drawing of many voting districts, such as Pennsylvania’s PA-7 district shown below.

Pennsylvania’s PA-7 district, however, is just one example. Voting districts all across the nation have become geographically irregular due to two gerrymandering methods called packing and cracking. Packing is the technique of cramming as many opposition voters into as few districts as possible. Cracking is the practice of spreading opposition voters out over many districts, making it impossible for their party to win the majority. Both methods dilute voters’ impacts by wasting votes that are cast for the losing candidate by partisan minorities in ‘cracked’ districts, or creating extra votes for winning candidates cast by opposition voters that have been packed into as few districts as possible.

Although the gerrymandered districts mentioned prior were driven by Republicans, gerrymandering is not just a Republican wrongdoing. In a 2002 election for the New York Assembly, Hakeem Jeffries (now a member of the House of Representatives) was gerrymandered out of his seat. The left-leaning drawers of the voting map carved out the block on which Jeffries’ house stood in Assembly District 57 so that people who had lived in this district for decades suddenly could not vote for Jeffries in the Assembly elections. Democrats are at fault for the same unfair drawing of districts in Maryland and Illinois, making the issue bigger than just a partisan conflict: it is a flaw to U.S. democracy as a whole.

Partisan gerrymandering is legal, and permitting the drawing of voting districts to advantage anyone who draws them presents a major structural problem to United States democracy. In 37 states, the legislators themselves are drawing voting districts with a clear interest in mind—to win the vote—and therefore put any candidate of the opposing party at an inevitable disadvantage. In these states, the districting pen holds too much power when it is a legislator, or anyone with a clear bias, holding it. When elections roll around, many voters end up wasting their votes and have no say in choosing their representatives; rather, the representatives hold the power to choose their voters.

While there are currently no constitutional limitations other than gerrymandering on the basis of race or minorities, the issue has become so significant that multiple Supreme Court cases are underway that highlight the disputes over gerrymandering. This districting problem has become more relevant than ever, and the court has the opportunity to review and perhaps change the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering.

However, even if the court rules against partisan gerrymandering, there are still questions regarding the problem of how to draw the districts. Some may say that the easiest way to solve the issue would be to use redistricting software that takes the process out of the hands of biased map drawers. Technology capable of doing this already exists, however there are costs and benefits to such scientific precision. Technology could make the districting process more fair by eliminating bias, or could increase the precision of which map drawers can unfairly gerrymander districts. For example, Wisconsin Republicans accessed voter data in 2011 and used high-speed computer technology to draw obscure lines to ensure control of the Legislature. The use of technology can only eliminate the problem of partisan gerrymandering if it is not abused by a biased administrator.

The reality is that there is no right way to draw voting districts. Voters should not have to worry about unfair gerrymandering diluting the impact of their votes. Technology can be used for good, but it can also be used to manipulate the drawing of districts to a more advanced degree. Dropping a grid doesn’t work either; while creating equal-sized, gridded districts may seem fair, the United States is not composed of square communities of equal populations. Regardless, districts should have representatives that serve their best interests–not the interests of whoever draws the map.