By: Alex Boylston

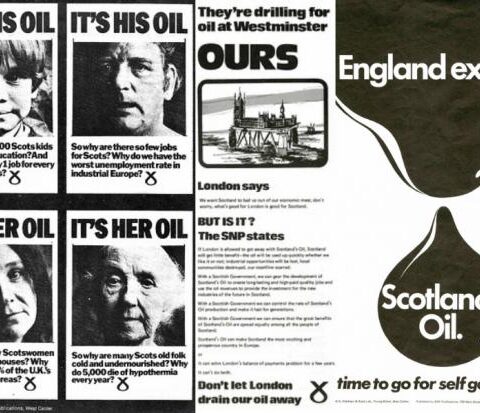

In a historic referendum held on Sept. 18, the citizens of Scotland rejected the idea of full independence by a margin of 10 percent. In the months leading up to the referendum, the Scottish National Party (the largest political party in Scotland) and its leader, Alex Salmond, aggressively campaigned for Scottish independence after the referendum was approved by the United Kingdom’s government in late 2013. Party leaders and the affiliated campaign “Yes Scotland” endorsed the stance that Scotland should be independent because Scotland and England had “opposite social and political views,” decisions regarding Scotland were made in Westminster and not in Edinburgh, and that England secured funds from North Sea oil reserves despite the fact that those reserves are found in Scottish waters.

Although they appeared in the news less frequently than the Scottish people, the people of Catalonia, a region in northeastern Spain that includes Barcelona, were marching in the streets prior to the referendum waving Scotland’s flag next to the “senyera,” the national flag of Catalonia, in solidarity with another group seeking independence. Although the Scots voted to remain a part of the United Kingdom, Catalonia’s leader Artur Mas said that this would have no effect on the Catalan people’s desire for independence. According to Mas, the Catalan people, though not ecstatic about the result of the Scottish referendum, would like the option of having an independence referendum like Scotland. Mas pledged on Sept. 22, a mere four days after the Scottish referendum, that he would petition for his region’s right to hold such a referendum after the Catalan parliament passed a law enabling him to do so. But the Spanish government in Madrid, as it has previously, stated that this was a violation of the Spanish Constitution and pledged to strike down the proposal and ban the referendum.

Catalonia and Scotland are not the first regions to demand self-determination in governance. In another notable case, Quebec, the predominantly French-speaking province of Canada, held two official referendums for independence in 1980 and 1995, both of which failed. Elsewhere in Europe, the Venetians, Sardinians, Basques, and Flemish have all petitioned for independence, but none have organized legal referendums. In Asia, the Uighurs, Tibetans, and Tamils have all petitioned for independence from their governing countries, but only the Tamils had a resolution after losing a war to the rest of Sri Lanka. Many international leaders feared that a breakup of the United Kingdom would cause it to lose face and economic prowess, but leaders of ethnically diverse countries such as China and Spain were more concerned about Scottish independence inspiring activists in their own countries.

The question that arises from this rather common situation is simple: What must a region have in order to be declared a state according to international law? There are two schools of thought on the matter: the declaratory and the constitutive theories of statehood. The former, seemingly the most prominent, says that a region is a de jure state if it has a defined territory, a permanent population, a government, and the ability to enter into relations with other states. By this logic, any one of the regions listed above would qualify as states under international law since many of them are based on ethnic ties to lands that date back centuries. However, in the eyes of the United Nations, the constitutive theory of statehood is the guiding philosophy. According to this theory, a state only exists if it is recognized by other states. The constitutive theory is generally useful in international bodies since it denies legal status to states created by force, such as ISIS or the Donetsk People’s Republic in Ukraine, but it also prevents de jure status for certain countries who are not recognized by enough countries. Take Kosovo, for example, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008 due to ethnic differences. It is a fully functioning state according to the declaratory theory, meeting all four criteria and even being recognized by more than 100 U.N. member states, but is relegated to de facto status since it is not recognized by enough countries in the U.N.

It is not fair to demand that any region desiring independence should be free from its ruling country since this can be impractical or unethical, as some states are created by force. But, after seeing a legal and fair independence referendum take place in Scotland, it is fair to suggest that legally recognized states should attempt to provide residents of these regions with a chance to choose their own paths through independence referendums. Does this mean full-fledged independence for all? No. A majority of Scots and Quebecois have accepted more autonomy from ruling bodies while countries such as South Sudan and East Timor have found amicable ways to split from their ruling countries and join the international community. The independence movements around the world, nationalistic in fervor or not, are not about independence, but instead about self-determination and choice regarding their futures.