Note: In this article, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria is referred to as Daesh after consultation with Carter Center employee Michel Osta regarding The Carter Center’s policy to refer to the terror group as Daesh. According to Osta, “Using ISIS or ISIL gives legitimacy to the group. By saying ISIS, you’re calling them the Islamic State, and that’s what they call themselves. Daesh also sounds like a mix of Wahesh (وحش) and Daes (داعس), and Wahesh means monster and Daes means ‘something that steps on’. It has a connotation of them being monsters and they hate that. And them hating it is another reason why we call them Daesh.”

Situated on thirty-five acres in East Atlanta’s Poncey-Highland neighborhood is the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, which details the former president’s political career and holds twenty-seven million pages of presidential papers archived in neat manila boxes stretching three stories high. The library and museum, encircled by gardens speckled with azaleas and a pond trickling to a Japanese garden, shares its architectural style and the surrounding campus with The Carter Center – the nonprofit organization Jimmy Carter founded in 1986 to continue his global mission to pursue peace and fight disease. The Carter Center is comprised of four interlocking rotundas teeming with vibrant artwork, priceless artifacts, and employees like Michel Osta – an intern in The Carter Center’s Preventing Violent Extremism Project who, among other responsibilities, analyzes Daesh propaganda.

Working at a desk inside one of The Carter Center’s middle rotundas, Michel, a Lebanese-American and University of Georgia student, examines Daesh websites and videos from a computer in an effort to discover their underlying message and prevent the propaganda from reaching vulnerable netizens. Michel has sifted through dozens of videos.

“Weapons, battle footage and all that. Footage of dead soldiers. Really horrible,” says Michel. These videos do not feature actors in a movie. This is real life. It could be someone in his last moments.

“There were a lot of times where we felt like we needed a break. This is too violent. Too much. Too sad,” he recounts.

Michel categorizes each propaganda video he watches using a multivariate thematic coding method as he searches for references to brotherhood or marginalization or violence – themes tapped by Daesh often wholly unrelated to Islam. After coding propaganda, The Carter Center uses these findings to train Islamic religious leaders throughout the globe on how to prevent deceptive themes in Daesh propaganda from influencing vulnerable community members.

“They have videos of themselves establishing themselves as a state, you know, collecting taxes, upholding the law and paving roads. There are some religious videos, very few though. Maybe seven percent of the videos are because of Islam. People don’t usually go for religion.” – Michel Osta

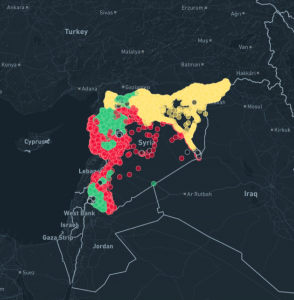

In another concrete rotunda is Christopher McNaboe, the director of the Carter Center’s Syria Conflict Mapping Project, who watches videos uploaded from locations across Syria with eagle eyes. Mr. McNaboe examines background buildings and surrounding ecological clues from online media postings in Syria to locate where in Syria the media post was uploaded from. Using this geolocation data, Mr. McNaboe and his team formulate a virtual map of the whereabouts of various organized groups in Syria such as Daesh conurbations and government-controlled strongholds.

“Syria is the first major armed conflict to have taken place in a very connected environment where many of the citizens have access to social media” says Mr. McNaboe. “What I started doing was experimenting with some social network analysis tools and social media analysis methods to see if there was something to be gained form that angle of analysis. And there was.”

The geolocation data is the groundwork beneath the Syria Conflict Map, which is publically available on The Carter Center’s website and availed by humanitarian organizations to ensure aid operations are conducted in nonviolent regions across Syria. Mr. McNaboe and his research team have pinpointed organized groups and tracked elaborate arms-funding networks, soldier defections and the frontlines of battles.

Leading Carter Center strategies for peace in Syria is Hrair Balian, the director of the Conflict Resolution Program who has accompanied Jimmy Carter on peacebuilding missions in nearly every Middle Eastern country. Mr. Balian superintends The Carter Center’s Syria Transition Dialogue Initiative, a program that arranges dialogue sessions between senior Syrian government officials, civil society representatives, political activists, academics, international policy experts, lawyers and other interlocutors to formulate the most practical and inclusive strategy for peace in Syria. I asked Mr. Balian if recent discussions from the Syria Transition Dialogue Initiative accelerated peacetime prospects within Syria. “No, everything is frozen. The whole Geneva process is frozen,” he interjected dejectedly from his desk inside the Carter Center. However, he remained hopeful that Carter Center peace tactics in Syria could attain delayed fruition, noting that “Conflicts like this are not resolved from one day to another – from one intervention to another – it’s a long, long, long involvement that can produce results some point in the future.”

A common thread running through each rotunda and peace program in The Carter Center is an unmitigated dedication towards attaining peace in Syria. While policymakers and international pundits may see conflict in Syria as a necessary evil, it never entered the equation at The Carter Center. And there is an understated and oft-unexploited value in formulating a strategy entirely focused on primum non nocere, notwithstanding low prospects for pacific solutions in the Middle East. Concurrently working towards nonviolent solutions to the Syrian Civil War, Michel, Mr. McNaboe, and Mr. Balian – each situated in different locations and grey rotundas and Carter Center programs – synergize efforts that fulfill Jimmy Carter’s fundamental objective behind The Carter Center: to wage peace despite penchants towards more truculent, knee-jerk responses to international conflict.