By: Andrew Roberts

![All I really need to know I learned in [pre-]kindergarten](https://georgiapoliticalreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/politifact-photos-Obama_-_Decatur_1.jpg)

Source: Politico

Like Mark Twain said, “Every time you close a school, you will have to build a jail. What you gain at one end you lose at the other. It’s like feeding a dog on his own tail. It won’t fatten the dog.”

The case for education reform is a simple one to make—GDP growth, worker productivity, non-pecuniary effects—but the case for the right form of education reform is far more difficult to make. Intuitive ideas like smaller class sizes and more experienced teachers are often ineffective and continue to leave the United States struggling to keep up with countries that excel in education.

The implementation of pre-kindergarten is an education policy that has received great attention recently. In 2013 and 2014, President Obama advocated for universal preschool in his State of the Union addresses. Recently elected New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio is looking to create a free pre-kindergarten program for his 4-year-old constituents. Across the country, California lawmakers are considering a similar measure in addition to similar proposals by lawmakers in Maryland, Texas, and Washington. This pattern has been sown nationally as states as a whole increased pre-kindergarten funding by almost 7 percent for the 2013-2014 fiscal year. Forty states across the country fund pre-kindergarten for a total of $5.6 billion.

But how effective is it? Research has shown that pre-kindergarten helps prepare children for kindergarten in areas including math, language, literacy, and emotional development. Beyond preparation for kindergarten, studies indicate that pre-kindergarten helps greatly with long-term school success quantifiers such as better test scores, higher educational attainment, and less grade repetition. Further, it can help lower rates of delinquency and crime later in life. This research comes from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), which offers research-based advice to policymakers and educators on early education issues.

The strongest evidence from the NIEER study found that economically disadvantaged children gain long-term benefits from pre-school. Despite this assessment, a study by the Department of Health and Human Services indicates that any gains made by children who enroll in Head Start, a federal early childhood education program for low-income children, level-off by the time that they are in first grade. The NIEER study acknowledges this deficiency, as it says that increasing subsidies for current federal policies is unlikely to produce any meaningful improvements. Obviously this is a problem, but it might not be so significant. Although many gains made by Head Start children are lost by the first grade, the program is not designed to make low-income children unequivocally superior students, but to close the persistent achievement gap that plagues them from an early age. As a remedy, the NIEER study recommends that pre-kindergarten programs for those under the age of 4 should preference low-income children to help counteract this achievement gap.

In addition, the NIEER study says that public investment in state and local pre-kindergarten programs with high-standards will lead to the most effective results. What have been the results of the state programs that New York City, California, and other states aim to replicate?

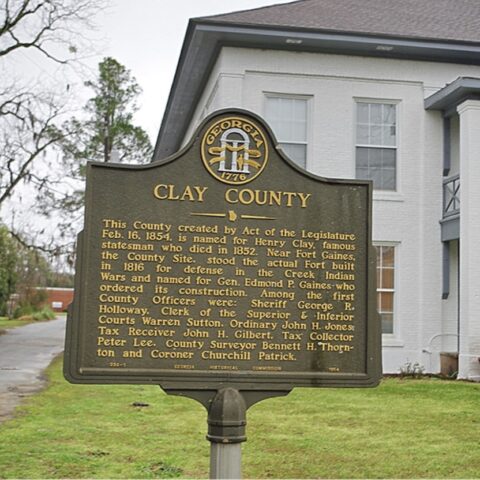

Another study by the Department of Health and Human Services did extensive work on the Georgia pre-kindergarten program. The system was established in 1993 with the creation of the state lottery, at the same time the HOPE scholarship was established. Children in the program made significant gains in vocabulary, letter-word recognition and expressive language, and mastery of basic skills. Further, disadvantaged children who participated in the program were more likely to overcome the achievement gap that they faced. President Obama even visited a Decatur school to praise the Georgia pre-kindergarten program after his 2013 State of the Union address.

Pre-kindergarten is another intuitive idea that isn’t perfect, however, as it is not the silver bullet solution to fix this education problem. The achievement gap still persists and pre-kindergarten is not a cheap program. Still, if states are willing and able to make the investment in their younger citizens, it might well be worth it. Different studies have calculated the return on investment, and for every dollar spent on pre-kindergarten the average return is anywhere from two to 17 dollars. These economic benefits come from higher income earnings (with greater tax revenue for the government), less incidents involving courts and jails, and greater positive externalities to the public—less damage, health costs, and suffering.

Open the school and close the jail. Let’s feed the dog by funding pre-kindergarten.