By Sandy Davis

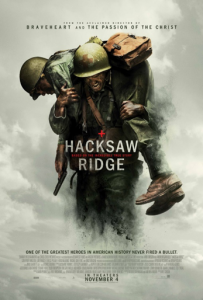

Harkening back to the film days of “Saving Private Ryan” and “We Were Soldiers,” Mel Gibson’s “Hacksaw Ridge” is an attempt to fuse the violence of the blood-soaked Second World War with the home-grown convictions of faith and peace. “Hacksaw Ridge” follows the true story of World War II hero, Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield), the first conscientious objector to be awarded a medal of honor. In Okinawa, Japan, Private Doss is credited with saving 75 soldiers in one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Despite the controversy surrounding Mel Gibson’s personal life, “Hacksaw Ridge” promises a moving tale as much at war with itself as its characters are with each other. At the very core of this film, “Hacksaw Ridge” strips away the viewers’ nuanced understanding of war-time glory to reveal a relatively unexplored understanding of heroic grandeur.

Born and raised in Lynchburg, VA, Desmond Doss’s life compellingly contrasts with the film’s picturesque images of the rolling Appalachian Mountains. Raised as a Seventh-Day Adventist, Doss struggles with the convictions held by his pious mother (Rachel Griffiths) and the abuse displayed by his traumatized father, an alcoholic, World War I veteran (Hugo Weaving). This violence in turn motivates Doss to become a peaceful and faithful man, much like his mother. A short time after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Private Doss meets and falls in love with Dorothy (Teresa Palmer), a hospital nurse, while his brother Hal enlists in the army, much to the disappointment of their mother and father. Doss himself is soon following on his brother’s heels, enlisting himself as a conscientious objector as much for his moral as his patriotic convictions.

Doss’s troubles, however, only begin there. Soon after enlistment Doss moves away to begin basic training. When it is revealed that he will not touch a gun for his personal beliefs, things go from difficult to nearly impossible. Encouraged by Captain Glover (Sam Worthington) and the colorful Sgt. Howell (Vince Vaughn), soldiers and officers alike begin to berate and beat Doss for his convictions. What many of the soldiers see as an open defiance of the established order, commanding officers see as a virus which, when spread, will affect the morale of the soldiers around him. After a series of psychiatric interviews, Doss is eventually court martialed on the charges of refusing to obey the orders of a commanding officer. However, after Doss’s father makes a sweeping entrance into the proceedings, Private Doss is summarily legitimized as a conscientious objector and allowed to enter the war without any form of a combative weapon.

Source: NPR

Once able to join the battlefield, it becomes obvious that Hacksaw Ridge is the sight of utter devastation. Gibson’s ferocious and unrelenting style is not lost on viewers as images of mangled legs and bare bones saturate the screen in bloody chaos. Named for its imposing, monstrous geography, Hacksaw Ridge is the sight of one of the bloodiest battles of World War II. This fact alone fuels some of the most gruesome images of the film and Gibson spares no moment to envisage the sheer carnage of the war and destruction seen by Doss. However, the moment of the hour has arrived and it seems that Private Doss was put on the earth for such a moment as this. And in this moment, he makes a choice to return for the fallen men on the battlefield, even with no one there to protect him. Instead of retreating behind the ridge along with the rest of the United States battalion, Doss offers up a prayer of courage to the Lord Almighty and plunges into the thick of battle armed only with a satchel of morphine and a bible gifted to him by his wife, Dorothy. The film then becomes a montage of hiding, morphine-induced dragging and lowering until the final count weighs in at 75 rescued soldiers.

Nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and (well-deserved) Best Film Editing, “Hacksaw Ridge” is produced in the same style as many others films; however, it explores many moral and psychological facets not commonly associated with its genre. It is a film about war, yet it is not wholly a conflict between persons. More so, “Hacksaw Ridge” is a 21st century approach to an age-old moral dilemma: the ethics of killing. The film does less in exploring the tenets of nationalism and does much more in evoking moral pride at the thought of saving life in war, as opposed to taking it. This visually graphic portrayal of war offers up a stunning perception of conflict that still remains wholly at the margins of the ethical and psychological dilemmas of real-life trauma.