By: Carson Aft

In our memories and our textbooks, the 20th century is a long procession of inequality and injustice. The long history of disenfranchisement in the American South ceased to be a process but became an art. Whether through poll taxes, “literacy tests,” or intimidation, the political machines in power managed to ensure that only the bravest African-Americans even attempted to vote below the Mason-Dixon. The promise of a voice was backed by an unsigned check from the federal government. After several ineffective attempts at mitigating racial discrimination, real progress came in the form of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. America marched closer to equal representation. Those efforts remained effective until a warm summer day more than 50 years later.

On June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court took it upon itself to strip the Voting Rights Act of its main strength: oversight. Striking down the key equation that established which states and areas would be scrutinized due to past discrimination, the Supreme Court changed the playing field for minorities challenging voting practices. The decision of the Roberts Court set back racial policy in America by removing current restrictions on voting laws, stagnating the process of oversight, and displaying a dedication to states’ rights over individuals’ rights. Rather than simply amending a functioning process, the Supreme Court crippled an invaluable force of progress in American racial equality.

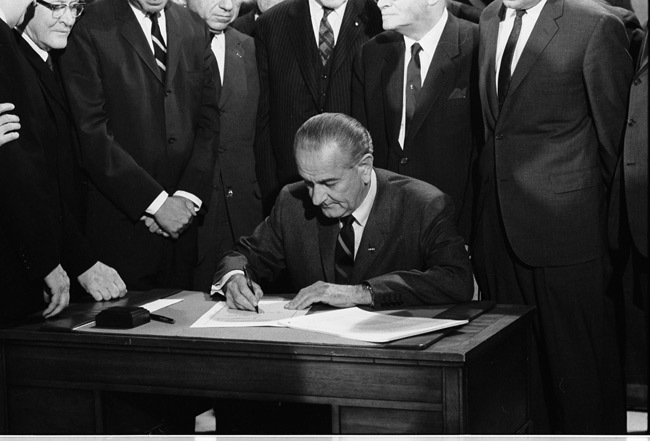

In the wake of the events at Selma, Alabama in 1965, a new response was necessary. Something new and bold would be the only solution to the blood spilled for the sake of a voice. The difference between the previous solutions and the one pushed through by President Johnson was that the new one had a legitimate, unavoidable process by which voting laws would be judged. Rather than relying upon lawsuits and judicial action like the previous laws had, this act rested its power in the automatic oversight granted to the Department of Justice whenever states that had a history of discrimination changed their laws. This ensured new laws in Alabama, Mississippi, and other incriminated states had to be objectively non-discriminatory to be implemented. These states were selected by a standard that was still fresh in the mind of President Johnson: literacy tests. Those that had recently implemented discriminatory literacy tests would need the blessing of the federal government in order to establish and practice new voting laws.

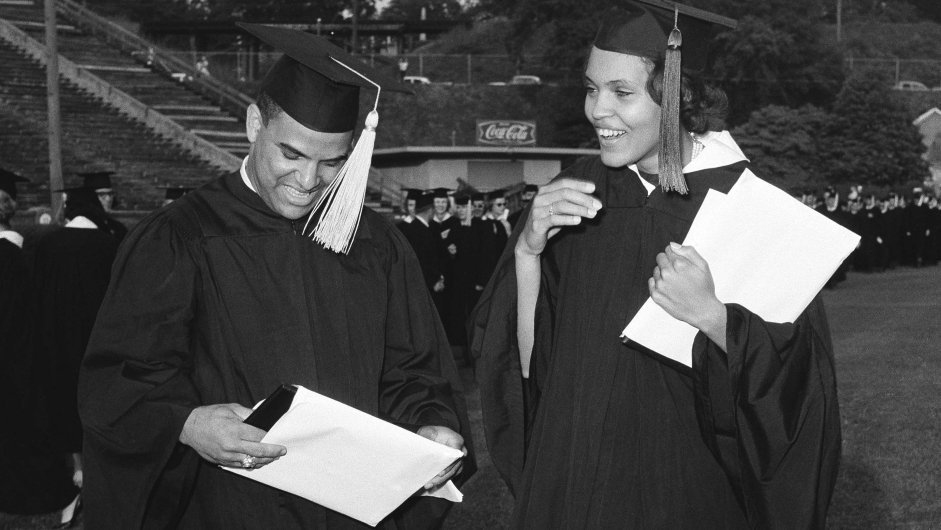

The number of new African-American voters jumped dramatically, showing that the law had serious impact. It was not until recently that the selection of these states was questioned, as those states with a history of discrimination tended to be the states that should be watched. The Supreme Court’s removal of these conditions stemmed from a desire for equal protection for the states, as guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment. The original intent of the law was not to single out states, but rather to use historical data to determine the states that needed to be checked. The highest court decided that, because the data was not necessarily as current as possible, the process should be shut down. This makes sense, but it puts Congress in a poor position, as well as allows for discrimination before a new process is established.

The original passage of the voting Rights Act of 1965 was difficult, as representatives of each state that would be scrutinized had to vote against the autonomy of their own state. If not for the impetus of the heavily broadcast atrocities in Selma, public opinion, as well as support from legislators, may not have been able to push the bill through. Without such heavily publicized and horrendous acts of discrimination, public opinion (especially in states that would be covered by any new law) may have never reached the crescendo necessary to pass a new formula or process.

Rather than simply eliminating a poor process, the Supreme Court’s recent decision guaranteed that no new process can readily or easily be put into place. Exercising the power to strike down legislation, they made revision infeasible. Any discriminatory spirit still alive can now manifest itself into cleverly discriminatory laws in any state in America.

The rationale for the highest court’s decision is not entirely unreasonable. Roberts reasoned that the data that was used to determine which parts of the country require oversight was decades old, and no longer relevant. Districts that may have discriminated before certainly can and have changed their ways. In addition, the Fifteenth Amendment guarantees that no voters can be discriminated against explicitly because of their race (though this does not prevent states from putting burdens on minority voters like longer wait times, restricted early-voting, and contentious voter ID laws). Some find this a compelling argument as to why the Voting Rights Act is unnecessary. Unfortunately, that rationale stems from an understanding of our government as it should be, rather than it actually is.

The autonomy of the states can be understood as a way for each individual part of the country to set its own objectives and priorities. It is derived from the autonomy of the people of the United States, each having freedom and opportunity guaranteed by their country. The masses can choose the direction their state moves, as well as the course their country sails. Whenever the people of a state are deprived of their rights, however, it invades the autonomy of the states. The only justification for the sovereignty of states is the sovereignty of their people. By choosing the rights of states over the rights of their residents, the Supreme Court showed their loyalties lie to government, rather than people. People without their rights, especially the right to vote, limit the legitimacy of their government more than oversight ever could.

It is true that the process for determining which states receive oversight needed some revision, especially after 50 years of use. It is impossible, however, to believe that the current inequalities and injustices can be countered by hobbling the law that was put into place to mitigate those societal woes. Through removing this process, they moved against progress, created a situation in Congress that will invariably lead to inaction, and chose “We the States” over “We the People.” The Supreme Court was not wrong to force change, and their method of change only serves to combat legitimate equality. Something is better than nothing, and nothing is worse than inaction.