By Grant Mercer

As a newly-formed nation, the United States could not compete with the cultural icons of its mother country. Absent from American lands were castles, cathedrals, and centuries-old cities. Americans soon realized that their country’s grandeur would not be measured by man-made structures, but rather by the land itself. Majestic mountain ranges, roaring waterfalls, towering sequoias, and canyons steeped in beauty and mystery would become America’s defining glory. National parks developed out of a need to safeguard these American treasures. This protection is needed now more than ever as America’s national parks have come under attack by sources within.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service (NPS), the agency charged with protecting and preserving American national park lands for the education and enjoyment of this generation and future ones. Now national parks have come under attack by a source far different than any anticipated by the NPS. Many of today’s conservative political leaders, propelled by profit motives, are leading the potentially most damaging charge against preserving America’s public lands.

America’s first national park, Yellowstone, was created by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872. At the time, it was not considered a revolutionary conservation concept, but rather the solution to a territorial dispute. Yellowstone’s lands lay within the boundaries of three territories – Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Each wanted the land to be declared a state park, but each of these territories were eighteen years away from statehood. While early explorers had marveled at the land’s beauty, it was not accessible by railroad and could not be farmed. Congress approved the first national park, feeling that since it had no economic value, no one would really care about the land’s usage. In addition, legislators had witnessed the exploitation of Niagara Falls, as the surrounding land was bought up by private individuals intent on turning a natural wonder into a pay-per-view peep show. Just in case Yellowstone should grow into a site that Americans would actually want to visit, they did not want it to share the same fate.

In 1906, President Teddy Roosevelt signed the American Antiquities Act into law. This act granted the president the authority to set aside federal land and sea regions to protect them from development and commercial exploitation. These lands are designated as national monuments, the first step on the route to becoming a national park. Since then, presidents of both parties have used the power of the Antiquities Act to protect public lands in all 50 states.

From 2000-2010, national leaders came together in a rare wave of bipartisan agreement to support national parks. Then-First Lady Hillary Clinton started the Save America’s Treasures initiative to protect historical buildings. President George W. Bush endorsed a National Parks Centennial Challenge program, which raised nearly $1 billion to maintain park lands. During that same decade, Congress passed dozens of national parks bills, including acts to restore the Everglades, provide protection for endangered species within Lake Yellowstone, and prevent erosion at Acadia — all with unanimous support from both sides of the aisle.

Today, Washington’s bipartisan work to protect America’s parks and public lands is a distant memory. Since 2010, legislators have pressed to sell off millions of acres of public lands, while gutting laws which help protect at-risk public lands, including the Antiquities Act and the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Since 2013, Congress has introduced over 50 bills that would remove or undercut protections for national parks.

This change in the political landscape is not due to the public’s change of heart. A 2014 Hart Research poll indicated that 88% of Americans want their legislators to take a strong stand in support of preserving the national parks. This congressional shift also does not appear to be related to actions of President Obama. Each of the national monuments created by his administration have largely been supported by the local communities and their elected officials.

Instead, this congressional shift can be traced to a highly conservative bloc of 20 legislators, opposed to federal lands, no matter their purpose. Dubbed the anti-parks caucus, these vocal senators and representatives share a viewpoint sharply different from the majority of both their colleagues and the American public. This group is informally led by Rep. Ron Bishop (R-UT), who is a founding member of the Federal Land Action Group (FLAG), an activist group devoted to the disposal of national public lands. Bishop has spent the last three years pushing for the sale of all of Utah’s public lands. Another member of the caucus, Rep. Ted Poe (R-TX), introduced H.R. 1931, which would force the sale of 8 percent of federal lands (the equivalent of 36 million acres) to the highest bidder every year until 2021. Caucus member Rep. Don Young (R-AK) proposed H.R. 3650, a statute that would allow states to seize up to two million acres of public lands (an area the size of Yellowstone), freeing the states to use these lands however they wish. The common thread uniting these anti-conservation politicians is their allegiance to the Tea Party and to FLAG. As members of these political groups, many congressmen feel the need to flaunt their conservative credentials, proving to voters that they are opposed to any controls over American lands imposed by the federal government.

Congressional opposition to national parks is not new. President Teddy Roosevelt immediately used his authority under the Antiquities Act to preserve 16 national monuments, including the Grand Canyon, Crater Lake, and Mesa Verde. Designating these lands as national monuments, the first step in preserving these areas as national parks, drew the ire of legislators representing mining companies’ eager to extract copper, zinc, and asbestos from these western lands. President Franklin Roosevelt pushed for purchasing the lands slated to become the Smoky Mountains National Park, much to the chagrin of southern senators with long-standing ties to logging groups. After President Jimmy Carter used the Act in 1978 to protect Alaskan wilderness, Sen. Ted Stevens (R-AK) announced that the federal government, intent on depriving Alaskans of basic human rights, had declared war on the state, provoking angry protests from Anchorage to Juneau.

In this election year, the Republican Party platform calls on Congress to “immediately pass universal legislation requiring the federal government to convey federally controlled public lands back to the states.” While the platform’s language does not specify which federal lands will be their target, the national parks, with their untapped resources, would undoubtedly be seen as a way to fill the Treasury Department’s coffers. The platform also calls for amending the Antiquities Act to require congressional, rather than presidential, approval for the designation of national monuments as well as approval from the home state, with all of these agreements coming within three years. This amendment would effectively gut the Antiquities Act, as the United States has yet to experience two houses of Congress and a state government coming to agreement in such a short time.

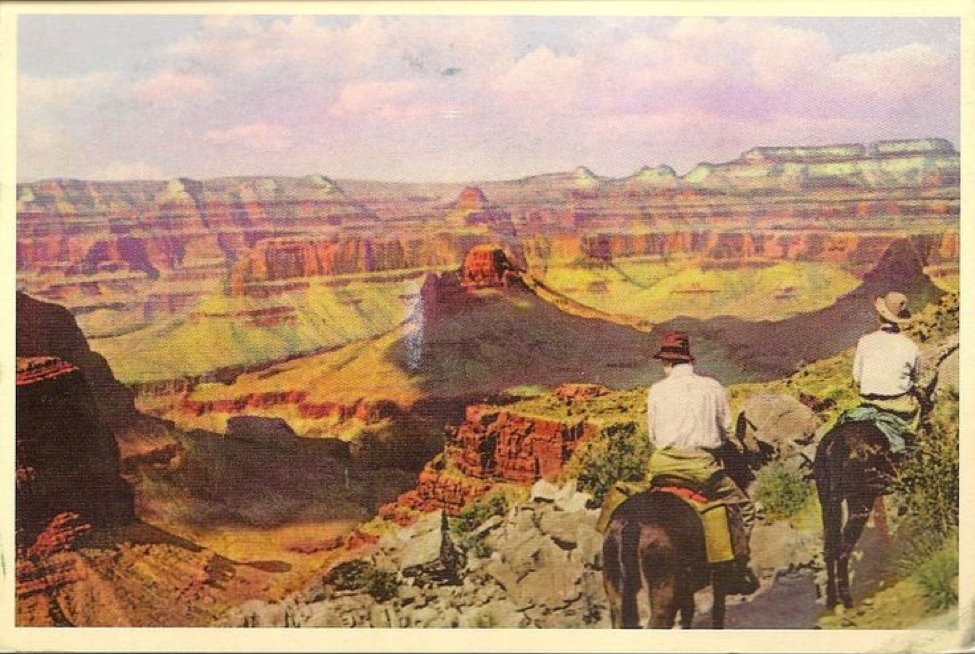

Critics often assume that national parks are too costly, with an annual operating budget of $3 billion. However, national parks generate more than five times that amount from visitor spending and have created nearly a quarter of a million jobs. Not only are national parks a shared American heritage, they are also an economic boon to the local areas in which they are located. After all, would the streets of Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg be lined with eager-to-spend tourists if not for the adjacent Smoky Mountains? Would over 5 million visitors travel each year to remote Arizona, spending approximately $450 million on hotels and adventure tours, without the Grand Canyon? National parks bring prosperity to areas in need of jobs.

The purpose of national parks is to tell America’s story. It is a shame to see the political enemies of public lands determined to end a century-old tradition of protecting these natural wonders, which would forever end that story. President Franklin Roosevelt said it best: “I see an America whose rivers and valleys and lakes — hills and streams and plains — the mountains over our land and nature’s wealth deep under the Earth are protected as the rightful heritage of all the people.” As the NPS celebrates its centennial, Americans must refuse to let this short-term anti-parks fever destroy “America’s Best Idea.”