By Phillip Jones

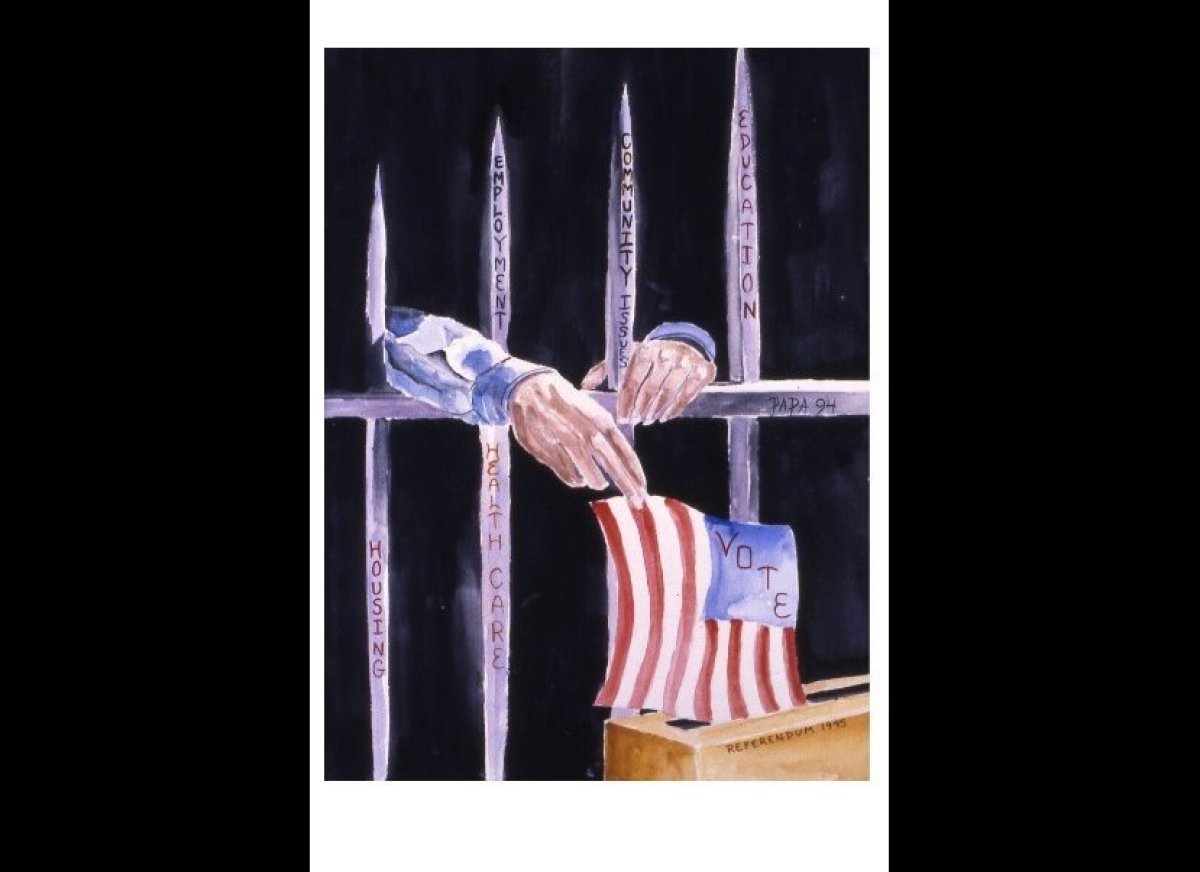

In the United States, many assume that voter disenfranchisement is a thing of the past: Jim Crow Laws have been abolished, the Voting Rights Act has been signed, and universal suffrage has become the standard. However, more than five million Americans will not be voting in this year’s presidential election, not because they are apathetic, but because they have been legally barred from voting due to their criminal record.

These restrictions, commonly know as felon disenfranchisement laws, are a deplorable barrier to millions of American’s right to political participation and should be removed. Ex-felons, like any other citizen, are affected by a country’s policies, and therefore should have a say in choosing the leaders who create and enforce these policies.

Felon disenfranchisement laws can be defined as any legislation that excludes people from voting due to a conviction of a criminal offense. 48 states, with only Vermont and Maine as exceptions, currently have some form of felon disenfranchisement legislation, making these laws a norm nationwide. The widespread implementation of these laws in the United States, paired with our tremendous incarceration rates, makes this a serious issue. Few developed countries deprive such a large group of their population, which in America’s case are disproportionally low-income individuals and groups of color, from such a basic civil right.

The intensity of these laws varies across the country. Many states, such as Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, only bar those who are currently serving a prison sentence from voting. However, as of 2016, there 18 states that also bar the right to vote for those who are on parole or probation.

In some states, the consequences of a felony conviction are more severe. 12 states, including Kentucky and Florida, temporarily or permanently revoke ex-felons’ right to vote, even after they have fully left the criminal justice system. An advocacy organization called the Sentencing Project estimates that, as of 2010, 5.8 million Americans were disenfranchised because of felon disenfranchisement laws. This represented around two-and-a-half percent of the American voting age population at the time.

Such a large statistic is overwhelming, yet incomplete. As with American mass incarceration, this system of felon disenfranchisement overwhelmingly affects minorities. As of 2014, African Americans are 5.1 times more likely to be imprisoned compared to whites. Because of this higher rate of incarceration, they are also nearly three times as likely to be disenfranchised because of their past felony convictions. While these policies do not overtly target minorities like policies of the past, their discriminatory effect is obvious.

This system also disproportionally burdens poorer American citizens. Not only are low-income citizens more likely to be imprisoned in the first place, but also they find it much more difficult to repay their legal financial obligations (LFOs) in order to get off probation. The Alliance for a Just Society defines LFOs as “any fines or fees that accompany a citation or conviction,” which can include fees owed to the court, monthly probation fees, or even bills for a stay in jail. In order to complete a probation sentence and recover voting rights, payment of these LFOs is usually required. Considering that the LFO totals can vary from a few hundred to several thousands of dollars, these obligations can be framed as a grueling cost for those on probation to regain the right to vote, which poorer America citizens may not be able to pay.

Many advocates and politicians have challenged felon disenfranchisement laws by claiming that they are unconstitutional. Some assert that the laws conflict with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Others argue that the overwhelming effect of felon disenfranchisement laws on minorities violates the Fifteenth Amendment, which states, “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

However, the unconstitutionality of felon disenfranchisement laws is far from definitive. In Richard v. Ramirez (1974), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the California felon disenfranchisement laws in contention were constitutionally permissible. This was because they did not believe these laws actually conflicted with the Equal Protection Clause.

There is similar discord about the racial argument on the unconstitutionality of felon disenfranchisement laws. Often, the argument is not whether these laws are justifiable, but rather if the federal government even has the power to ban them. This is because, while these laws disproportionally affect African Americans and other minorities, they are technically color-blind laws. Therefore, there is a disagreement about whether the federal government can justifiably ban felon disenfranchisement laws based solely on their discriminatory effect. For example, Dr. Richard Hasan, a Professor at Loyala Law School, believes that “under today’s standards, Congress will have to come up with significant evidence of intentional state racial discrimination to justify a felon disenfranchisement ban under its 14th and 15th amendment enforcement powers.”

Opinions on this issue vary across the political spectrum. Roger Clegg, President and General Counsel at the Center for Equal Opportunity, claims that “people who commit serious crimes have shown that they are not trustworthy.” However, it should be noted that the United States is an outlier in the developed world on this issue. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2005 that voter disenfranchisement based on felony convictions was a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights. Similarly, in Canada, Israel and South Africa, voting restrictions based on convictions are illegal.

These countries are correct in prohibiting felon disenfranchisement. Ex-felons are not morally corrupt individuals who have forfeited their right to vote through participating in crime. They should be thought of as citizens who deserve the rights any other citizen possesses.

It is time for the United States to follow the actions of other developed countries. With America’s massive ex-felon population, the consequences of inaction are too large to be ignored. Locking someone out of political life is not justifiable because of a past action, especially considering that they have paid their debt to society through prison time. As more Americans come to terms with our country’s mass incarceration problem, advocates for change should press the problem of felon disenfranchisement in order to ensure that disenfranchisement becomes a thing of the past.