By: Darrian Stacy

What happens when you cross a pop-like rapper and a Christian rapper on the fringe of their genre with opposing views? A hip-hop beef is born of course, but not over the things we’ve come to expect out of a proper rap feud, like conflicts that typically arise from a subliminal diss in a track or neglecting to show proper respect to rap’s royal class. No, in this case the resulting beef is one that addresses a sensitive social issue: gay rights.

On the heels of Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ notable Grammys performance of their song “Same Love” last month –during which Queen Latifah officiated a mass wedding of 33 gay and straight couples– Christian-based rapper Bizzle released his own version of the hit anthem. Whereas the original version of “Same Love” advocates for gay rights and acceptance, Bizzle’s version, titled “Same Love (A Response),” is the exact antithesis of the song. Despite all the hype characterizing the controversy an interpersonal battle between the Macklemore/Ryan Lewis duo and the Houston-based rapper, however, Bizzle’s religious rhymes seldom addresses the pair. Instead, he opts to aim his objections directly at the LGBT community.

In his song, Bizzle focuses on the important contemporary issues arising as a consequence of the LGBT community, like the apparently rampant trend of gays and lesbians “violently assaulting people” and “attacking old ladies.” If you wade through the more ridiculous parts of Bizzle’s verses (like equating gays with pedophiles) though, Bizzle intones at least one idea that has been and will likely continue to be prominent in the gay rights debate. He sums it up nicely in 11 bars:

“And I feel so disrespected that you were so desperate/ You would compare your sexual habits to my skin (What?!?)/ Calling it the ‘new black’/ Tell me where they do that/ They hung us like tree ornaments, where were you at?/ They burned us for entertainment, you go through that?/ Mom’s raped in front of they [sic] kids, while they shoot dad/ Ever been murdered just for trying to learn how to read bro? (Nope.)/ A show of hands?/ I didn’t think so/ So, quit comparing the two.”

The “new black argument” that Bizzle lays out can’t be dismissed as easily as the others because it isn’t actually an argument that he created. Prominent leaders like Maryland’s former Lt. Gov. Michael Steele, civil rights activist Rev. William Owens, and others have leveled the same complaint. But for all those who criticize the comparison, there are just as many others like Coretta Scott King and President Obama who consider the comparison wholly appropriate.

The fact of the matter is that Bizzle is justified in reminding people of the battles fought in the pursuit of civil rights for African-Americans. As Bizzle so eloquently points out, many travesties were committed against the black community, and are made even worse when perceived with a modern eye. Although not fully articulated in Bizzle’s verse, the root of the “new black” idea stems from a concern of undermining the meaning of ‘oppression’ by using it too freely. In an interview following the release of his song, Bizzle commented that the comparison is unacceptable because once one begins to compare the similarities in the struggles one is also then allowed to point out the differences, which in his view come down to the severity of plight.

While the issue of the appropriateness of the comparison is simple to encapsulate and worth examination, the solution is equally simplistic and something which Bizzle’s perspective already accomplishes: reinforce the differences in both the gay rights and civil rights movements. Despite what some gay rights activists may proclaim, gay is not the “new black,” but that doesn’t mean that the two movements aren’t similar in many regards. In this debate if one feels the civil rights struggle is being minimized, it’s certainly equitable to highlight contrasts. All civil rights movements share commonalities, and comparison is appropriate as long as each is understood within its own context.

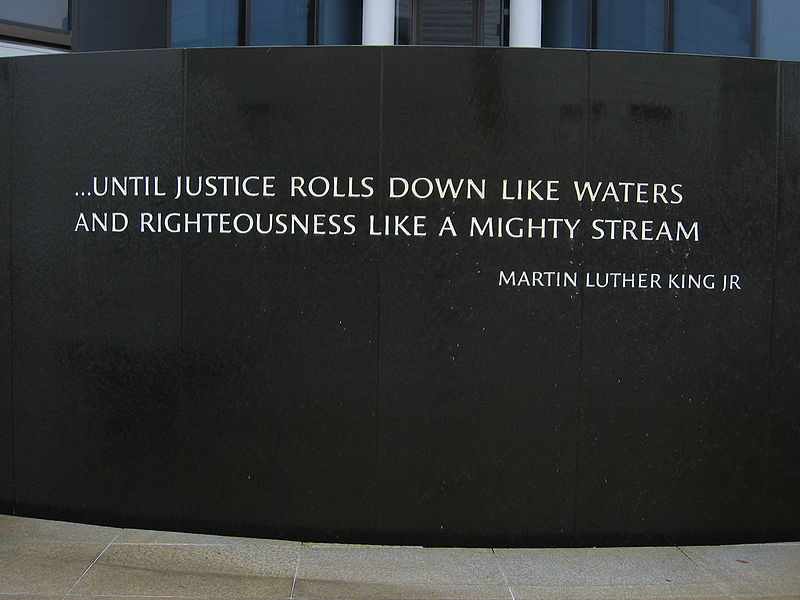

But for Bizzle and others who share his beliefs, it’s not enough to just accentuate the differences of the two movements; in their view, members of the LGBT community aren’t really oppressed if actually compared with the struggles of African-Americans. As their reasoning goes, oppression has a color, and in the United States it’s black. The truth, though, is that black people don’t possess a monopoly on oppression. The logic that you can’t compare two civil rights movements and can even dismiss one because they vary in severity doesn’t follow. In a country in which sexual orientation bias remains the second greatest cause of hate crimes, and LGBT employees are allowed to be openly discriminated against in some states, Bizzle’s ideas disregard a fundamental theme of the civil rights movement. Dr. King reminds us: “an injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Even if two groups face different challenges, a movement doesn’t have to pass a “brown paper bag test” of oppression, one which would first require an examination of one’s ethnic background, to qualify for the title.

Of course, that’s not the end of Bizzle’s commonly espoused argument. He and others don’t just think the two social movements can’t be compared because of a difference in the level of strife, they also think such a comparison is inappropriate because gays can “play straight” whereas blacks can’t “play white.” But Bizzle’s own words betray the problem with this reasoning. Consider if black’s could “play white;” it would be entirely unacceptable to prescribe “whiteness” as a way to live comfortably in society. Poll a military service member who served under the policy “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.” Just as it is offensive to suggest that blacks should hide who they are if they could, it is equally offensive to suggest that gays should hide who they are. The claim also doesn’t clarify why members of the LGBT community would even have to “play at being straight” if they don’t suffer from the aforementioned oppression and discrimination.

Meanwhile, detractors playing the “black strife card” help to prove Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ point; “Gay is synonymous with the lesser,” the lesser individuals and apparently the lesser struggle. The biggest problem with Bizzle’s claim is that it remains to be seen how the comparison of the two struggles harms the black community. Conversely, sounding the metaphorical racial alarm by consistently espousing exclusionary beliefs about oppression has clear consequences on the perception of African-Americans. Although eluding the stereotype in recent years, Bizzle’s comments contribute to the once prevalent perception of homophobia within the black community. Unfortunately, as long as there is an active gay rights movement this particular debate is unlikely to cease. Going forward however, we can analyze the similarities and the differences between the two movements, as long as the significance and dignity of both are preserved in the process.