By Rob Oldham

Director Richard Linklater took a calculated risk when he began producing “Boyhood”, possibly one of the most ambitious films released since the turn of the century. It was 2002 and there were many questions in front of him as he embarked on a 12-year journey to produce a coming-of-age story that would become nothing short of a cinematic masterpiece. The plot would revolve around a 7-year old boy named Mason and follow him as he grew up in suburban Texas, ending when he enters college at the age of 18.

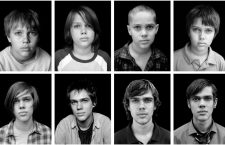

The only catch to what appeared to be a fairly standard script? Linklater would actually film Ellar Coltrane, the actor who portrays Mason, as he grew up.

For several days each year from 2002 to 2014, the production team would meet and film several scenes that usually center on Mason, his older sister, his mother, and his absentee father. The final result was a nearly 3-hour film that is eerily effective in capturing the mood and common experiences of relatively privileged, 20-something college students who grew up in the early 2000s while also speaking to the tragic brevity of youth. It was immediately lauded by critics and is considered in some circles to be a shoo-in for Best Picture at the 87th Academy Awards.

What makes “Boyhood” so compelling is that many of us college students lived very similar lives to Mason and his sister Samantha. The movie is essentially being filmed in real time with major events like the Iraq War, Barack Obama’s 2008 election, and the highly-anticipated midnight release of “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince” shown from the same perspective that many of us had during our own adolescence.

“Boyhood” does not try to do too much with what it has though. Unlike many films which try to capture the strangeness of experience, “Boyhood” basks in the glory of the ordinary. Mason is a normal kid and he matures like one. He is exposed to sex, alcohol, and drugs in the same manner that many of us were. He is a bit of a slacker during school and work, but he can be profoundly moved by some of his inspirational mentors. He does not know quite how to react when his mother breaks down as he moves away to college. There is no dramatic death in his family or tragic car accident. And though many in the audience waited for one, the movie never achieves a climax on a single event. The camera is merely a silent observer in the ordinary life of a typical millennial kid.

Unfortunately, some of Mason’s experiences are all too normal for the millennial generation. He comes from a broken home as his parents divorced shortly after he was born. Recent statistics indicate that nearly half of all marriages are ending in divorce, making Mason’s story a fairly common one for college age audiences. His father, portrayed by Ethan Hawke, is a genuinely good person, but is quite immature at the film’s beginning. As Mason grows though, his father matures with him and eventually remarries and gets a steady job. They form a strong bond throughout the film, but Linklater never attempts to create the perfect father-son story so often seen in cinema. It is much more realistic, as Mason occasionally is disappointed by his father (especially when he sells a classic car he promised to Mason). But, like most teenagers, Mason grows to love his father despite his flaws and to cherish their special relationship. This breaks away from the Hollywood cliché of father-son relationships which are usually portrayed as either completely perfect or totally fractured with suppressed feelings always simmering under the surface. “Boyhood” resists this stereotype and depicts a relationship that mirrors what most fathers and sons actually go through.

“Boyhood” is not all simplicity and realism, however. Like any good work of art, it slips in its two cents on the human condition. As Mason matures, he becomes philosophically inclined and begins offering pointed commentary on the happenings in his life. Mason’s musings revolve around the film’s themes, including another Hollywood cliché: growing up.

In a memorable scene at the University of Texas, Mason and his girlfriend discuss their fears about leaving high school and staying together throughout college, a familiar scene to many of us. During their discussion, Mason wonders if college will actually change him or if it is just another step in his life, no different from any of the others. He questions whether or not it is truly a transformative experience, pointing to his mother as an example. Despite her college education and several degrees, the film depicts his mother’s involvement in three failed marriages, her struggles to maintain steady finances for the family, and her rocky relationship with Samantha. In Mason’s words, “she is just as confused as we are.”

The film seriously questions whether there is such thing as a coming-of-age and if people actually ever grow up. This is especially important to the many college students who may wonder if they are actually maturing and gaining wisdom at university, or if it is just another necessary step in the social construct. In this sense, “Boyhood” is a sound board for the repressed thoughts of an entire generation, a unified rallying point for the strangeness of the millennial experience that it shines a candid light on.

“Boyhood” captures the millennial experience so eloquently because it is the millennial experience. Ellar Coltrane was not trying to act as he is if he was growing up; he is growing up, along with the rest of the cast. Sometimes the audience feels like the only difference between Mason and themselves is that Mason is being filmed. “Boyhood” is unapologetically genuine in its depiction of white, middle-class suburbia during the 2000s. It is a vastly important film in that it asks the audience to look inside themselves. It makes us wonder if the life of the boy we see growing up is really someone else, or if it is a mirror image of our own all-too-short adolescences.