By Shuchi Goyal

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 edition of the Georgia Political Review.

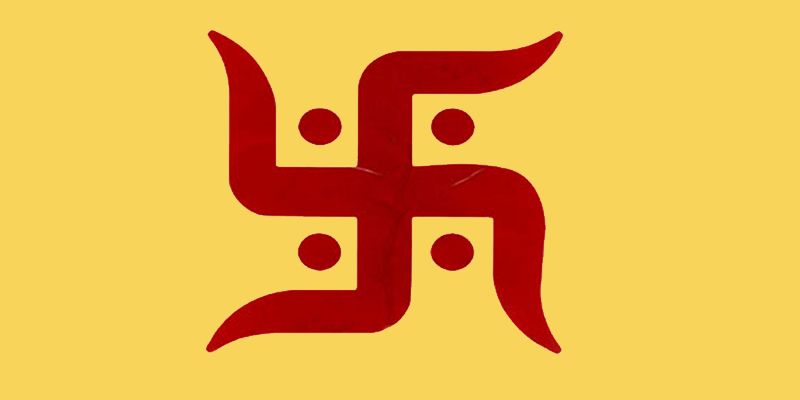

In the late autumn every year, my family, along with over 800 million other Hindus around the world, celebrates Diwali, the festival of lights and the marker of the new year. Our neighbors in the United States now expect to see the Christmas lights in our bushes in October and to hear the bangs of firecrackers at night. Indoors, we host a quieter affair as my sister and I ignite tea light candles in front of an idol of Lord Ganesha and arrange them into patterns. First we make an Om, which resembles a “3” wearing a crown. Then, we carefully arrange the candles into a hooked cross, making the swastika.

The Om and the swastika are auspicious symbols in Hinduism, believed to bring peace and good fortune to devotees. Yet I wonder what would happen if any of the 2 million Hindus in the United States displayed a swastika outside their homes, as people in India have done for centuries. Would our neighbors mistake us for racists? Would we find egg yolk dripping down our front doors the next morning? Would toilet paper hang from the trees in our yards?

In the Western hemisphere, few signs are as reviled as the swastika. The swastika has been banned in Germany since the end of World War II, and there have been numerous attempts to ban it across the European Union as recently as 2007. These proposals have failed because of laws protecting free speech, even if it is discriminatory. Yet, few elected officials have acknowledged that the swastika could be used without malicious implications.

Meanwhile in the United States, the Anti-Defamation League connected the swastika with anti-Semitic hate crimes until recently. Then in 2010, the organization’s director Abraham Foxman declared that the definition of the swastika had been broadened to a “universal symbol of hate . . . against African-Americans, Hispanics, and gays, as well as Jews.” He continued by calling it “a symbol which frightens.”

Yet for thousands of years before Foxman’s declaration, the swastika existed as a revered multipurpose icon, outlasting entire civilizations. The ancient Phoenicians, Greeks, and Egyptians all independently used the swastika as far back as 1200 BCE. The most prominent and continuous use of the swastika, however, began over 5,000 years ago in India with the advent of Hinduism. It represents positive energy and the core tenet that one is everything and everything is one. When Buddhism and Jainism developed later in the same region, the swastika became significant to religions as well. Today, the swastika remains an omnipresent symbol in South and Southeast Asia. People paint it on top of their doorsteps, the walls of their homes, the backs of their vehicles, the fronts of their skin. It is also visible in virtually every religious ceremony.

The swastika existed primarily in the East until the late 19th century, when a German archaeologist named Heinrich Schliemann found it on artifacts discovered in Troy, possibly brought there by ancient Indo-European migrants. He concluded that the swastika linked Western people to their “Aryan” ancestors and represented pride. From there, the swastika rapidly spread into the Western hemisphere as a sign of good luck, appearing on wedding dresses and even in the nose cone of the plane Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927.

Schliemann’s erroneous connection between the swastika and European ancestry took a new tone when it was incorporated into the German völkisch movement, a period of late 19th century nationalism coinciding with growing anti-Semitism. Nazi theorists and leaders like Alfred Rosenberg further adapted the swastika into symbol of victory for the ancient Indo-Aryan invaders, whom they claimed as the ancestors of the Aryan race and based their racial hygiene theory upon. In 1920, the German Nazi party formally adopted the swastika as a political symbol. Within just 30 years, the symbol sacred to Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism – religions that teach peace and coexistence above all else – would become equated across the Western hemisphere with the murder of 6 million Jews and 5 million other victims, including Romanis, homosexuals, and people with disabilities.

Most practicing Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist immigrants in Western nations observe the swastika privately out of respect. They keep it off their jewelry and clothing and confine it to their homes. The swastika has been used to intimidate members of several minority groups, so many people understandably perceive the image as a threat; a person who, for example, spray-paints swastikas outside a Jewish fraternity house, almost certainly intends to cause fear. If the tragedy of the Holocaust did not guarantee irreparable damage to the swastika’s reputation, the symbol’s subsequent adoption by Neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups definitely has. It is too difficult to reverse the deeply entrenched belief that the swastika is a hateful symbol among such a large group of people.

The fact remains, though, that by calling the swastika a “universal symbol of hate,” Abraham Foxman made a bold use of the word “universal.” Today, about 1.28 billion people, or nearly 20 percent of the world’s population, are Hindus, Jains, or Buddhists. For at least 1.28 billion, the swastika retains its original meaning: harmony, not hate.

Members of these religions were not asked for their opinions or approval in the 1880s when many Western archaeologists, not just Schliemann, came to the mistaken but seemingly harmless conclusion that the swastika represented ancestral pride. In fact, most Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist adherents at the time were otherwise occupied fighting a system of oppression in countries occupied by Western colonial powers. They were completely removed from the abhorrent misuse of the swastika in the West. Without anticipating it, they now find themselves in a world where they must constantly defend a symbol of cultural and spiritual value against Western confusion and, often, anger.

The swastika is beyond redemption in the West, but its history contains modern relevance when the phenomenon of cultural appropriation has been scrutinized numerous times in the last year alone. Like many current objects of cultural appropriation, the swastika was native to a systematically disadvantaged group of people. It was redefined in a supposedly inoffensive way by a population in power, probably without intention of harm. Yet the new group never sought the invitation or consultation of the original knowledge-bearers. Its meaning eventually became so heavily distorted that it bore no resemblance to the original. Today, the incorrect definition has become the widely accepted one.

Rejecters of the concept of cultural appropriation often argue that culture can only be shared, not stolen. In this instance, though, the appropriation of the swastika has necessarily led to a cultural loss for Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists living in the Western hemisphere – the loss of the ability to safely and freely express a part of their faith.

And while the swastika is an extreme case of a symbol of peace transforming into a symbol of genocide, it is not alone among powerful icons gradually taking on negative connotations. Navajo-themed clothing sold at Urban Outfitters is apparently meant to represent worldliness, when really it links the company with materialism and inauthenticity. Nor does cultural appropriation belong solely to the West. In the Middle East, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has adopted the battle flag of the Islamic prophet Muhammad as its own, even though the group acts against every teaching of Islam and targets primarily Muslims as its victims. To the fear of Muslims around the world, the flag, deeply symbolic of Islam and Muhammad’s teachings, is now being used to represent terrorism to the world.

When I see modern cultural appropriation, I worry because I know well what might lie at the end of its current path. In America, it is either too late or too soon to try and revert the meaning of the swastika to its original positive message, but a symbol does not need association with murder to be rendered useless. Gross misunderstanding and ignorance are enough.