You may not realize it, but that Health application on your iPhone is good for a lot more than just counting the number of steps you take each day. It contains valuable information, tracking and personalized advice on health topics from nutrition and body measurements to vitals and reproductive health. There’s even an option to enter a “Medical ID,” which can provide your medical information to someone else in case of emergencies. This application is constantly updating and improving and is part of a much larger initiative emerging in public health called mobile health, or mHealth.

mHealth is a relatively new concept; so new, in fact, that no standardized definition exists. One description, from The Global Observatory for eHealth, defines mHealth as medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices, through the use of communication through calls and text messages as well as features such as GPS, Bluetooth technology, and 3 and 4G systems. Projects span from appointment reminders and patient monitoring to emergency calling lines and raising awareness over health issues.

Though the advanced nature of these technological services may only appear applicable to high-income countries, mHealth is actually seen as an opportunity to bridge the huge gap between healthcare needs and service delivery in lower-income countries. The World Health Organization claims that mHealth “has the potential to transform the face of health service delivery across the globe.”

The unique advantage of mHealth is its ability to capitalize on existing resources rather than needing to develop new ones altogether. There are over 5 billion wireless subscribers to mobile cellular networks in the world, and 65 percent of these subscribers live in low- and middle-income countries. Even in remote areas of low-income countries where medical infrastructure is lacking, many people have access to mobile phones. This presents healthcare workers with a valuable opportunity to wield existing technology and resources for providing underserved populations with information on how, when and where to seek care.

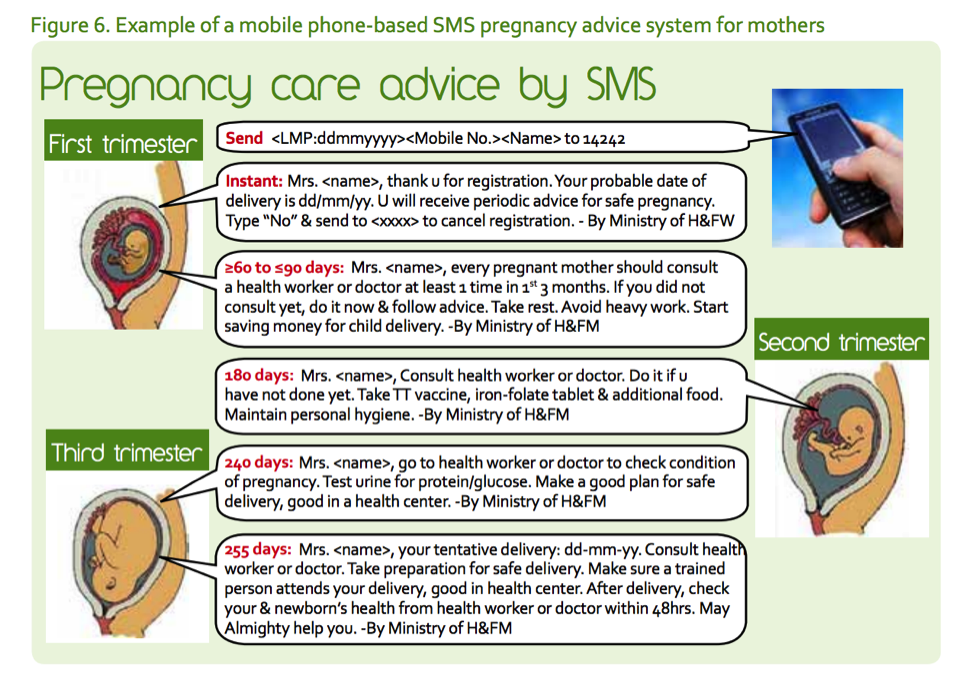

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Bangladesh, for example, has taken advantage of the country’s increasing number of mobile phone users to improve the health of its citizens. In 2007, the Ministry launched a project to encourage citizens to get their children on National Immunization Day by sending SMS text messages to all mobile phone numbers in the country. After noticing a positive response from the campaign, the Ministry extended this project to raise awareness of other health campaigns, such as National Safe Motherhood Day and National Breastfeeding Week. By 2010, pregnant women in rural areas of the country could register to receive prenatal advice by gestation age.

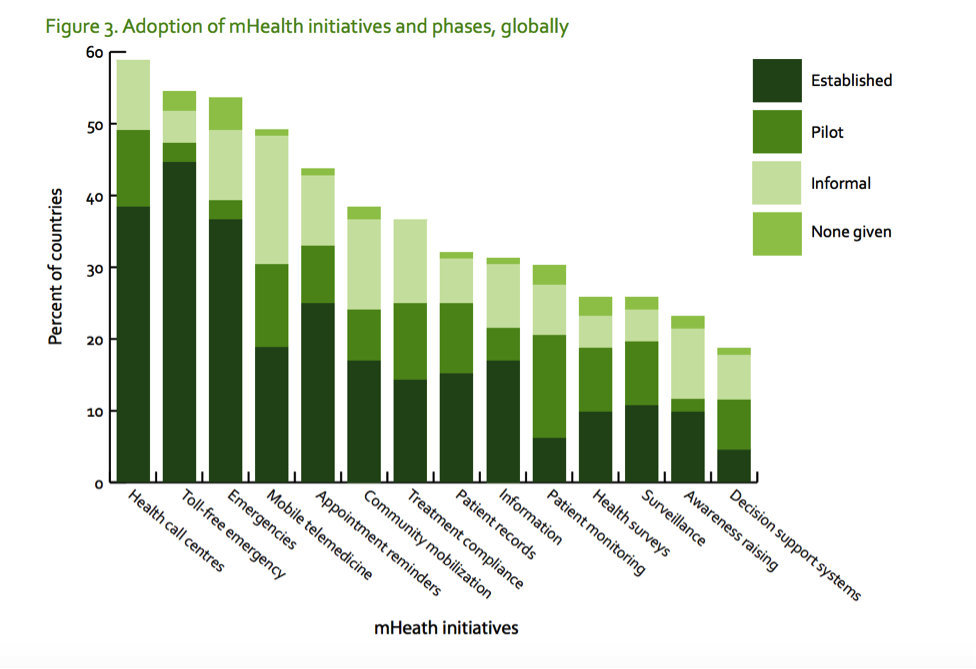

The WHO and United Nations see mHealth as a catalyst for reaching the Millennium Development Goals—the UN’s targets for addressing extreme poverty and human rights—particularly those aimed at improving maternal and child health and reducing the burden of diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Governments across the globe are taking part, with 83 percent of UN Member States reporting the use of at least one mHealth initiative. Some of the most common initiatives reported were health call centers and toll-free emergency calling lines, though many states also reported the use of initiatives like community mobilization and appointment reminders.

WHO data of Member States’ adoption of mHealth initiatives, second global survey on eHealth, 2009

The Harvard School of Public Health is taking a leading role in this new field, with professors launching programs focused on improving maternal and child health and tracking and preventing the spread of disease. One assistant professor, for example, developed a text message application that allows nurses in rural Kenya to alert a main blood bank about shortages before the situation becomes an emergency.

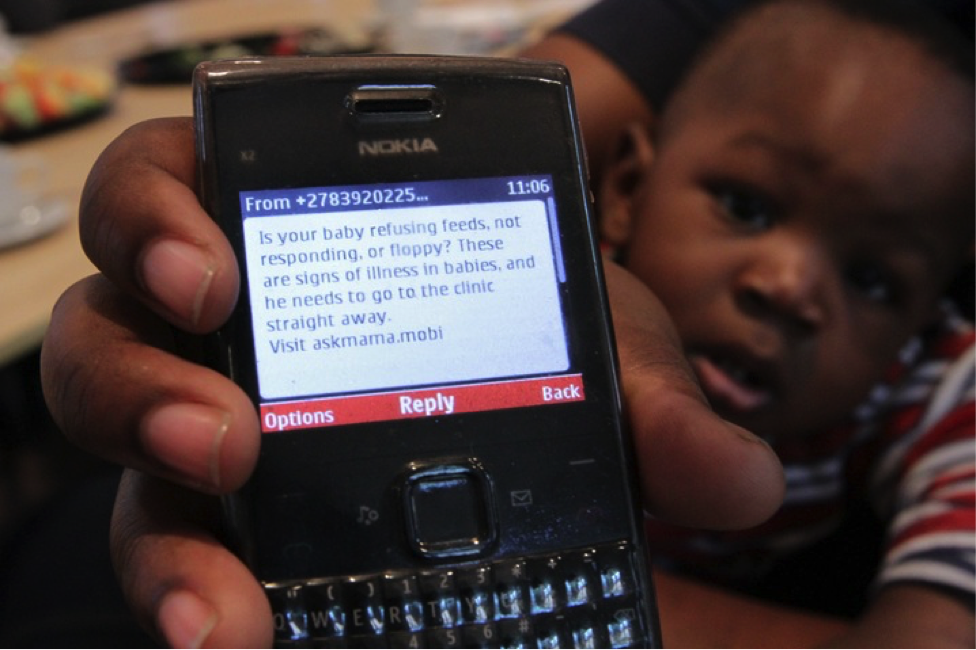

Students and faculty at the University of Georgia are also getting involved. Dr. Juliet Sekandi, a Ugandan native, physician and UGA professor of Global Health, has taken a strong interest in the field of mHealth. She was inspired to take action after visiting her home country three years ago: “I noticed that a lot more people in the population owned personal mobile phones even when they didn’t have access to basic needs like potable water and electricity,” she says.

Photo: World Health Organization

Dr. Sekandi is particularly passionate about using mobile technology to improve maternal health in rural Uganda, a serious issue in the area. Between 2011 and 2015, Uganda experienced 343 deaths by pregnancy-related causes per 100,000 live births, a staggering maternal mortality rate compared to 14 per 100,000 in the U.S. In the same time period, Uganda’s rate of neonatal mortality, or number of infants dying before 28 days of age, was 19 per 1,000 live births, once again unacceptably high compared with four per 100,000 in the U.S.

According to Dr. Sekandi, these high rates have a lot to do with the lack of information and awareness of what to do or where to go when health issues arise. Because of the limited availability of healthcare services and poor infrastructure, women in rural areas of Uganda must be extraordinarily proactive in their search for healthcare, especially during pregnancy.

Dr. Sekandi hopes to use mHealth to empower pregnant women with vital information such as where to go for prenatal care and birth assistance from trained health workers, early warning signs for problems associated with pregnancy, and where and when to take their babies for immunizations.

Along with a team of students, which she hopes to expand in the future, Dr. Sekandi plans to launch a pilot program in Uganda this summer. This team, a new club called MobileHealth at UGA, is currently focused on collecting old phones, developing a text messaging application containing educational information related to maternal health, and fundraising for the future.

Dr. Sekandi, although very hopeful, believes that the project’s greatest barriers will be in bringing the effort to scale and making it sustainable. Proper funding, she says, will be necessary to keep up with demands for the services this project can provide.

According to the second global survey on eHealth, many WHO Member States are still in the experimentation phase of implementing mHealth projects. There is a need for further information and evaluation of the effectiveness of certain mHealth applications. If mHealth initiatives are to become priorities, they must be properly evaluated and proven a worthwhile use of scarce resources, especially in lower-income countries.

But the potential for success is evident. As mobile technology constantly improves and the reach of subscribers expands, mHealth seems to be an inevitable and promising next step in improving healthcare around the world. And while developers continue to create technology for high-income markets – like the iPhone Health app and a new smartwatch device that reminds users to take medications when they eat – Dr. Sekandi’s project shows that mHealth can capitalize on existing resources to reach underserved populations with the greatest need for healthcare improvements.