By James Haverly

It’s about time we bring a long-forgotten cousin back into our embrace. From Cuba’s independence to its revolution in 1959, the U.S. enjoyed significant influence over Cuba’s economy, culture, and government. This made sense, as Cuba is only 22 miles from the Floridian coast. Unfortunately, a sense of animosity had replaced feelings of brotherhood between the nations, marked by a 50-year American embargo on the small island-state.

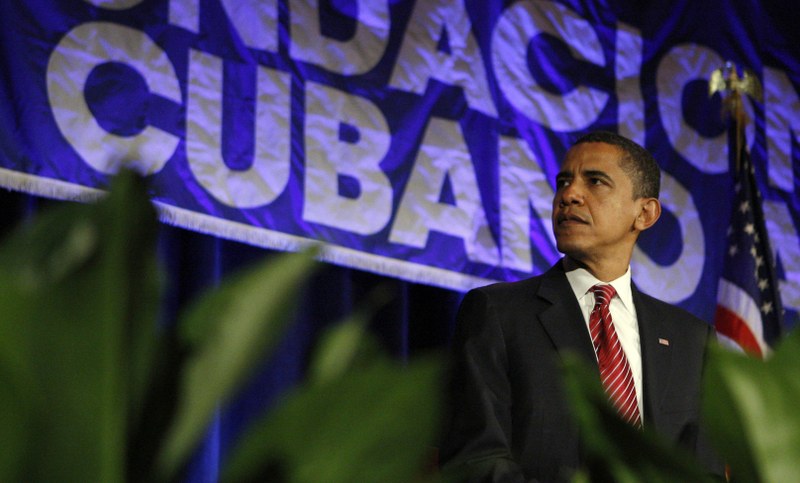

Recently, this embargo has been brought to the front of American politics due to Obama’s new pledge to normalize relations with Cuba. To many, this seemed a decision long overdue. The Castro regime has proven stable, foreign investment in Cuba has skyrocketed, and relations between Cuba and American allies, namely the European Union, continue to warm. In short, the embargo has failed to alienate Cuba from the international stage.

Multiple organizations have criticized the U.S. embargo. In 2014 the United Nations nearly unanimously passed a resolution, as they have almost every year, calling on the U.S. government to drop the embargo. Human Rights Watch reported multiple times that the United States’ insistence on maintaining the embargo intensifies, rather than ameliorates, the hardships the Cuban people face.

U.S. allies, too, bemoan the country’s policies towards Cuba. In particular, Title III of the Helms-Burton Act caused a great deal of bellyaching by international partners in the past. This law, signed in March 12, 1996, granted American citizens extra-territorial powers in lawsuits with foreign corporations and states, allowing any American to litigate if the foreign entity had ever “profited from the use of” seized American property in Cuba. Fortunately, a provision in the Act provided each administration the ability to waive Title III. This is the only reason the U.S. has avoided a larger diplomatic crisis with its allies. Indeed, international attitudes toward Cuba-U.S. relations have turned very much against the United States. It seems clear a revamp of the policy is needed.

Yet domestically, the public proves to be much more divided on the issue. Although a Gallup Poll has shown that the majority of Americans favor re-establishing diplomatic ties with Cuba in recent years, the anti-Castro lobby—consisting of mostly affluent, older Cubans—vehemently opposes any policy change on Cuba. In fact, Cuban senators from both sides of the aisle have condemned the move. Republicans Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz and Democrat Bob Menendez blasted Obama on what they consider a terrible negotiation strategy. Members of Congress have vowed to block funding for a Cuban embassy or appointment of an ambassador. Obama will still face an uphill battle in Congress if he aims to lift economic sanctions on Cuba.

Never mind the potential legislative challenges, President Obama has sound reason to believe re-establishing relations will benefit U.S. interests. Formalizing relations with Cuba for the goal of ending the embargo makes economic, political, and moral sense. The United States will benefit from lowered costs, foregoing those associated with maintaining the embargo. For example, the U.S. will no longer have to ensure that goods from all countries have no association with any American property seized by Cuba more than fifty years ago. Cuba would also prove to be a lucrative market for American exports.

There are political advantages to this move, as our allies in Europe would be able to rest assured that they are not liable for any lawsuit by a private citizen, as authorized by the Helms-Burton Act. Further, critics of the U.S. in the United Nations will lose a talking point about the perceived tyranny of American foreign policy.

Most importantly, dropping sanctions will weaken Castro’s claim that the United States antagonizes Cuba. Castro has used this argument to depict the dire economic situation as a manifestation of American foreign policy. The U.S. policy has allowed the Cuban leader to shift the blame from his own government’s shortcomings to an external government’s policies. If the embargo has done anything, it has only strengthened the Castro regime’s grip on the country, giving him the opportunity to rally his people around a perceived injustice. Indeed, Cuban officials have called the Helms-Burton Act a “gift from heaven” for the Cuban President, according to University of Miami Professor Joaquin Roy.

However, the unfettered flow of ideas, goods, and people between the two countries due to Cuban proximity to the U.S., coupled with Cuba’s relatively low population, will make it near impossible for Castro to head off moves toward democracy and improved human rights. Castro simply will not have the resources to block out American influence. As Canadian foreign affairs Minister John Baird put it, “The more American values and American capital that are permitted into Cuba, the freer the Cuban people will be.” Of course, accepting American ideals do not equate necessarily to greater freedom, nor will freedom only spawn from American ideas. Indeed, efforts by the U.S. government to curb net neutrality and its insistence on spying on its citizens, two among many possible criticisms, paint a contrary picture. Nevertheless, increased interaction between Cubans and Americans will only increase the Cuban people’s exposure to American norms which will strengthen democratic movements inside the island.

If none of these arguments convince those on Capitol Hill that Obama knows what he is doing on this issue, perhaps they should consider an overused, but applicable, adage: the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting certain results. The embargo tried to force the Cubans to capitulate in the 60s, it tried in the 70s, and in the 80s, 90s, and 2000s. For decades it worked to undermine the Castro regime, but Cuba has shown no sign of relinquishing communism. When will it be time to put this tired Cold War tactic to rest and find something more effective? For the sake of the Cuban population, it better be soon.