By: Sam Kinsman

Written from GPR’s Brazil Bureau after a formal study of Politics in Education in Brazil and a series of interviews and informal conversations with teachers and students in both public and private schools and universities.

Brazil has been lauded in recent years for its combination of economic growth, democracy-friendly policies, and new openness to take part in international politics that have brought it further onto the world stage. The Portuguese-speaking nation is tirelessly referred to as one of the four BRIC countries (along with Russia, India, and China) expected to dominate growth in the 21st century. On this business side, foreign investors have reacted by sending billions of dollars to the country to invest in energy projects and open up offices in the business capital of São Paulo. The U.S. government has also made Brazil its priority in Latin America, emphasized by Joe Biden’s recent visit to Brazil in June when he called “for a new era of relations” between the two countries. Although vague, at least one example of these relations was the dramatic increase in number of annual Fulbright scholarships to send American students to study in Brazil that jumped 500% over last year.

This optimistic view of Brazil is well supported. The country is endowed with an abundance of natural resources, including nearly every type of energy source from oil to biofuels to hydroelectric power. Its vast territory and population of 200 million people make it one of the world’s top agricultural producers (it is the world’s biggest exporter of coffee, soybeans, beef, sugar cane, and frozen chickens) and one of the most attractive consumer markets for domestic and foreign businesses. In addition, the country has attracted significant (and for the most part positive*) attention by hosting both the World Cup and the Summer Olympics over the next several years.

The discussion of Brazil, however, too often ends with its long term potential. It leaves out the enormous challenges the country faces today in the form of a slowing economy, a crumbling infrastructure, and perhaps most pressingly, an education system in need of major reform. Illiteracy remains relatively high, teachers are poorly paid, and public schools, particularly in the poorer areas of the country, are lacking basic infrastructure to teach their students. With these results, it is worth taking a look at the experience of a student today who is expected to grow into a productive worker that will help advance the country’s modern economy.

First and foremost, the good news is that the child is at least likely to be in school. Brazil enjoys an extremely high rate of child school attendance due in large part to the government’s Bolsa Família program that provides financial assistance to families whose children show up in school. Unfortunately, the same child who is sent to public school starts out on a path that makes it much less likely for him or her to graduate from college. Why? The quality of institution he or she will receive is simply insufficient. Poorly paid (and oftentimes just plain poor) teachers in public schools mean many students leave without a basic understanding of math and Portuguese. The rest, although literate, are usually unprepared to pass the competitive Vestibular Brazilian college entrance exam required to study at public universities and often do not have the financial means to pay for a Cursinho private preparation course to improve their chances.

Surprisingly, the scene of public education at the university level is precisely the opposite. The best tertiary education in the country is found at one of the federal or state public universities where students, for the fortunate few who find a spot, study for free. After graduating from one of these institutions, qualified workers in fields such as finance or engineering can command higher salaries than their counterparts in the United States. Even graduate students in Brazil who study for masters or doctoral degrees or for professional degrees like medicine or law do not pay to study (much to the envy of their American counterparts who usually graduate buried in student loan debt). Their education is financed 100% by the government.

The result of this system is that Brazil’s poorest families, who are without financial resources to send their kids to private school, end up remaining disadvantaged because they lack the university degree required to secure higher paying jobs. They have the option, of course, to try study through a private university, but end up paying hefty fees to do so. On the other hand, more privileged families send their children to the best private schools available which prepare them to succeed on the entrance exam and study at the free public universities. Ironically, these students who occupy the spots at public universities often come from families who could afford to cover the cost of an alternative private college education if necessary. The system, in short, promotes a continuation in inequality between social classes.

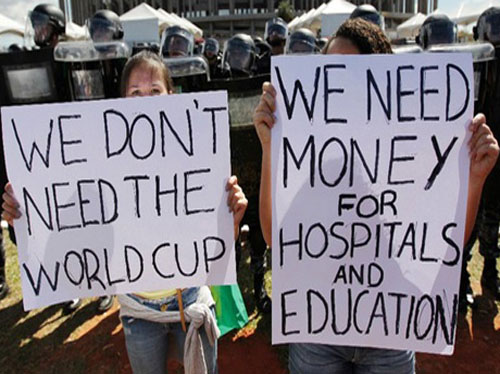

In Brazil, the expression “The country of the future” (O país do futuro in Portuguese), is commonly used by an optimistic population that sees the potential of their country to develop and take better care of its people. Unfortunately, this same phrase is used too by corrupt politicians elected with promises about the country’s future who end up stealing public money and doing little to take care of Brazil’s problems at present. For Brazil to achieve its goals of reducing poverty and inequality while continuing to develop, it will have to tackle the extreme mismanagement of public funds by a government plagued by problems of bureaucracy and corruption. Despite collecting more than 35% of GDP in taxes, infrastructure and education remain in need of long overdue public investment (the subject of the protests currently sweeping across the country’s major cities).

Education reform and investment are fundamental for Brazil to maintain its current “star” status. While not every public school teacher struggles to teach and not every public university student comes from a rich family, the clear patterns of these problems leave Brazil with stubbornly high inequality and insufficiently educated workers. Even public universities, which receive the lion’s share of education funding, are in need of expansion and further investment to be able to satisfy the economy’s demand for a higher qualified labor force. To stay competitive, in short, it is time for the Brazil to look beyond the new stadiums for the World Cup.

*The largest protests in 20 years currently happening throughout Brazil are linked, in part, to complaints about the large sums of money the government has spent on stadium and other projects for the World Cup (that protesters argue could otherwise be invested in the type of education or other reforms mentioned in this article). This topic is part of a significant movement in Brazil still unfolding and deserves its own article to be discussed in further detail. For more information, click here.