By: Angela Tsao

This Monday, Nebraskan officials of the Nebraska Public Service Commission graced TransCanada with a coy, “Yes, but…” as their ultimate decision to allow Keystone XL’s construction through the state. In its nine years of existence, the Keystone XL pipeline has been wrought with controversy– the largest opposition coming from environmentalist groups, who criticize numerous aspects of the pipeline extension.

Since the project’s inception in 2008, several routes have been proposed and reviewed by the State Department; meanwhile, the U.S. legislative branch has debated the pipeline in a long period of indecision. The pipeline is unique in that it requires a presidential permit for cross-border construction. Former President Barack Obama paused the issue by withholding that permit and ultimately decided the pipeline would not serve our national interests, vetoing a Keystone XL bill that had passed through Congress. However, President Donald Trump’s early 2017 presidential memorandum revived Keystone XL. Alongside this federal battle, the company has also needed to obtain permits from state and local levels. One last hurdle, approval by the Nebraska Public Service Commission, has the critical role of granting or denying TransCanada the power of eminent domain.

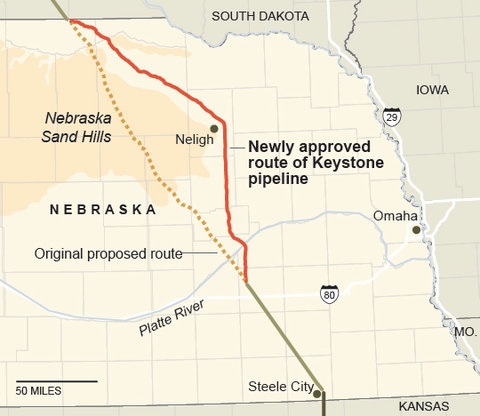

So what actually did the Nebraska Commission say on Monday? They approved one of the three routes proposed by TransCanada. The approved route, however, is not the company’s preferred option, as it is about five miles longer and will require an extra pumping station. TransCanada has responded unenthusiastically to the Nebraska Public Service Commission, stating that it will soon make a decision that takes into account the changes mandated by the Nebraska commission.

The preferred route would have cut through the Sandhills, a delicate region of grassy sand dunes. It came under fire for its potential threat to these sensitive regions of Nebraska. The mainline alternative route, which was approved, still runs through this area but largely avoids environmental upset. However, it also continues to go over some parts of the Ogallala Aquifer, the main water supply of the Great Plains (and specifically, countless hectares of farmland). The more localized risk of environmental damage can best be assessed by oil spills, like the standing Keystone’s 210,000 gallon leak just days before this vote for approval. The leak, and threat of future catastrophe, is particularly relevant for Native American tribes in the area who protest the environmental injustice.

The problem is that the Nebraska commission wasn’t supposed to take the spill into account. A 2011 state law forbids them from considering the possibility of leaks. Pipeline safety is something that the Federal government is supposed to handle. But President Trump’s rapid display of support for Keystone XL, and his blatant dismissal of the extensive reviews conducted by the former administration, indicate the Federal government’s lack of preparedness to properly fulfill this duty. The appointments and budget cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency have demonstrated a clear tendency of the Trump administration to favor fossil fuels. To ignore the reality of Keystone XL-related dangers is negligent.

The Keystone XL Pipeline is controversial even within the green movement. One argument of its supporters is that oil from the tar sands would have to be shipped regardless of the pipeline, and the alternative method–rail–is less efficient and safe. They are not entirely wrong. Not only is rail more expensive, but historically, it has 4.5 times as many spills as pipelines. Furthermore, trains are powered by emissions-heavy fossil fuels like coal. Pipelines, however, also have their fair share of problems. Of special relevance is the way they spill: continuous leaks too small for pressure sensors to detect, a silent threat that blooms undetected underground. Even when pressure sensors do detect leaks, as in the most recent South Dakota Keystone spill, the pipeline is shut down far too slowly. Since 2010, there have been 16 spills of greater magnitude than the South Dakota incident reported in the US. TransCanada has promised that Keystone XL will be the safest of pipelines. In all truth, Keystone XL will probably have a better track record than current infrastructure, but Nebraska should not have ignore its threat.

This all detracts from the larger argument, which is the dreaded discourse on climate change. Carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of all that oil flowing through the Keystone XL pipeline are a major environmental concern. The Alberta tar sands that will fill Keystone XL are low-grade fuels with an over-sized footprint. The extensive extraction process means that the finished oil from tar sands cost as much as three times the amount of emissions as conventional crude. Going back to the pipeline safety issue, tar sands oil is more likely to leak than conventional oil. Opponents of Keystone XL don’t want to see support for what is colloquially deemed “dirty oil.” Frankly, it should be disheartening for everyone to see any new, extensive, and expensive investments into maintaining the oil-coal status quo. Consider what a difference that money could make in the renewables sector. (Keystone XL is privately funded, but the point remains.)

Opposing Keystone XL actually can make a difference in the larger environmental movement. For one thing, the industry hasn’t reached its projected tripling of production yet. But also, many environmentalists view this as a symbolic fight, about values and knowledge. While many politicians speak of the large number of jobs that the pipeline will produce, the National Resources Defense Council’s investigative journalists pointed out that only 35 permanent jobs would be created from the eight billion dollar project. The question has become who controls the rhetoric, and who controls Washington. It’s easy to frame the problem in any way if there’s no political salience to investigate the truth. The disadvantaged groups most directly affected by the pipeline have good reason to fear its negative impacts– but so do the rest of us.

Optimists believe that Nebraska Public Service Commission’s sanctioning of the alternate route could push the battle in environmental favor. The change from the preferred route might put national review back on the table, requiring another round of environmental impact analysis from our government. Even if the controversy over this disputed part of Keystone XL pipeline centers around Nebraskan soils, however, it is up to our national leadership to advocate for change on the inherently international issue of climate change. The pipeline is itself transnational, a poignant reminder that the U.S. government ought to recognize its global impacts.