After a meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in early March, much of the media’s attention was focused on President Donald Trump’s responses related to the location of the U.S. embassy in Israel. Commentators speculated as to how his administration would work towards a durable peace in the region after decades of occupation and violence. Therefore, when Trump announced that his administration would no longer push for a two-state solution, the international community and media were both indignant. Ever since Israel seized the Palestinian Territories in 1967, both the United States and the international community at large have consistently supported a two-state settlement since such a solution would allow both Israelis and Palestinians to have their own territory in what they both claim is their homeland. As such, when Trump decided to no longer pursue what had supposedly been a cornerstone of American foreign policy for years, it seemed to spell the end of the two-state solution and any prospects for peace in the Middle East as we know it. However, in reality, the idea of a two-state solution has become increasingly less viable over the years for a variety of reasons, and Trump’s statement more or less reflects the reality in Palestine today.

The two-state solution was born in 1947 when the United Nations General Assembly voted to partition the western part of Mandatory Palestine into a state for both Arab Palestinians and Jews in response to mass Jewish immigration into the territory during and before World War II. The plan, seen as unacceptable to Jews since it made Jerusalem a UN-governed territory and unacceptable to both Palestinians and Arabs since it gave the Jews too much territory, was never fully recognized by either side. The ensuing war between Israel and its Arab neighbors was one of the first threats to the two-state solution; it not only resulted in Israel seizing more territory than it was originally granted by the partition plan, but the rest of the Palestinian territory was absorbed into Jordan and Egypt, leaving Palestinians stateless. The outcome of the 1948 war seriously hurt the prospects of a Palestinian state.

One occupation was traded for another when Israel conquered what is now known as the Palestinian Territories (as well as the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights) during the Six Day War in 1967. A few months after the war, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 242 unanimously, which emphasized the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war” and called for an Israeli withdrawal from all occupied territories. In 1973, the Arab countries attempted to take back the territories they lost in the war, and the international community continued to insist Israel end its occupation of seized territories. Most believed that the occupation could not continue forever since Israel had no claim to the territories under international law. However, the Six Day War resulted in a dramatic shift in attitudes both inside and outside Israel regarding the territories. While Zionism, the idea that the Jews are a nation and are entitled to their homeland in Palestine, was a largely secular idea whose founder was an atheist, it acquired additional religious dimension following the Six Day War since many religious Jews and Christians began to see the war as a “miracle” and blessing from God. This seriously threatened the possibility of an independent Palestinian state since followers of this resurgent religious Zionism believed that the occupied territories were given to the Jewish people by God and to return them to non-Jews would be tantamount to sacrilege.

Although he was not religious himself, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin was an ardent nationalist who firmly believed in the idea of a “Greater Israel” consisting of the conquered territories and enjoyed the support of many right-wing Israelis. Begin formed the Likud Party in 1973 from the merger of several secular right wing parties. When his party contested the 1977 elections, it was the first right-wing party to govern Israel since the country’s inception. However, it was only able to form a government by including religious right-wing parties in its coalition, all of whom were now devoted to religious Zionism and the territorial integrity of “Greater Israel.” Consequently, settlement construction in the occupied territories, though ongoing since 1967, skyrocketed under Begin’s government, with some estimating that the number of Jewish settlers and settlements quadrupled during his six years as Prime Minister. Begin, best remembered by the international community for signing the Camp David Accords in 1978 and earning the Nobel Peace Prize as a result, was supposedly bound by the accords to not only return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt but also allow some degree of Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza. Begin did indeed return Sinai and dismantle Israeli settlements there. However, in order to maintain the support of religious Zionists, he simultaneously committed to not only more settlements in the Palestinian Territories but also ensured that these Jewish population centers, often placed in “biblically significant areas,” would be dispersed enough to prevent the formation of any unified Palestinian state. When Western leaders questioned his intent and strategies, Begin argued that a Palestinian state would become a “Soviet base” and that Israel needed the West Bank for security reasons, the latter of which the Likud Party still uses as an excuse for why Palestinian statehood cannot be achieved.

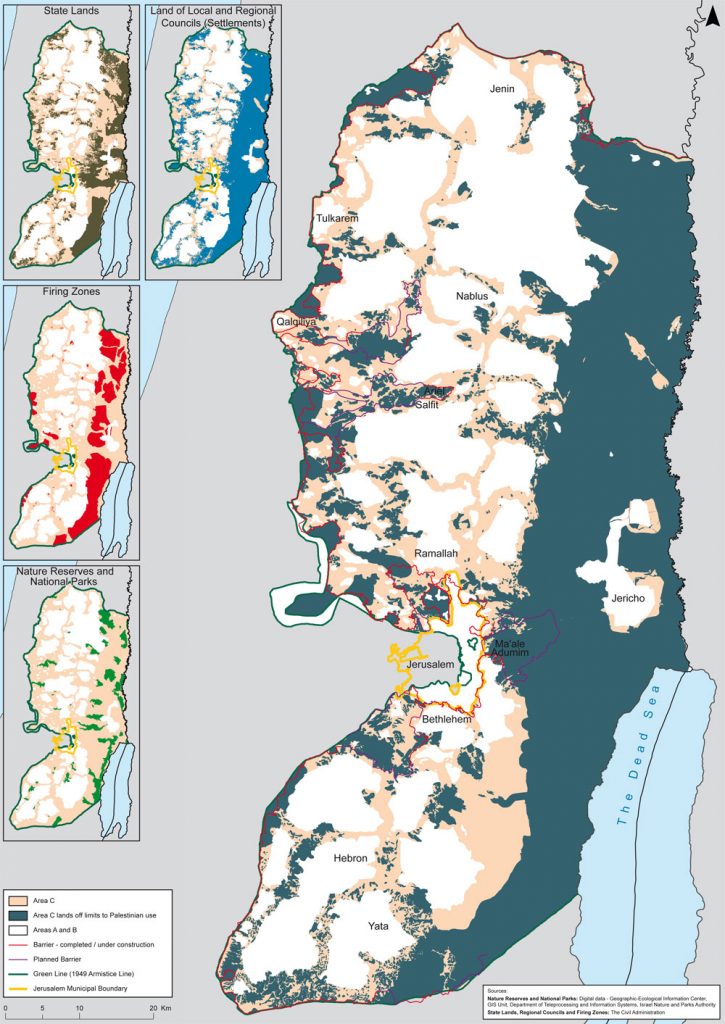

Hope returned for Palestinians when, after nearly 15 years of Likud rule, Yitzhak Rabin and his Labor Party managed to narrowly form a government in 1992 and began negotiating a settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These negotiations resulted in the Oslo Accords, an agreement in which both the Palestinians and Israelis recognized each other as legitimate entities while a new Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was created to govern parts of the West Bank. The Accords recognized the “territorial integrity” of a future State of Palestine consisting of the West Bank and Gaza Strip while also dividing the West Bank into three areas of control: one under exclusive control of the PNA (area A), one with PNA civil control but Israeli security control (area B), and one under exclusive control of Israel (area C). Although this seemed promising at the time and the PNA (now known as the Palestinian Authority or PA) became a permanent government for Palestine, it is rarely acknowledged that areas which the PA controlls under the Accords are not contiguous and that Area C, which is under full Israeli control and home to hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers, makes up 60% of the West Bank. What was once a temporary arrangement designed to gradually transfer control of land to the Palestinian government has lasted for almost 25 years. During that time, not only has the population of Jewish-only settlements in Area C continued to grow but barriers to Palestinian movement between PA-controlled areas, such as checkpoints, Jewish-only roads, and fences, continue to expand in the West Bank.

Except for sporadic diplomatic actions and negotiations undertaken by Israelis, Palestinians, and the United States in the years since the Oslo Accords, little else has changed since 1993. Although the United States has continued to push for a two-state solution and denounced settlements, even breaking precedent by allowing the UN Security Council to pass a resolution condemning settlements in December of last year, it has done little to actually move the process forward. In fact, Trump’s statement that he would rather have Israel and Palestine “directly negotiate” a peace agreement and then later seek U.S. approval is more or less just repeating what his predecessors have been saying since the Oslo Accords.

However, to Israeli PM Netanyahu, there is little incentive to head to the negotiating table. The status quo, where Israel maintains control over the occupied territories but does not grant Palestinians living there citizenship, is the best option in lieu of integrating millions of Arabs into Israel as part of a one state solution or losing territory as part of two-state solution. As a result, Netanyahu and his predecessors continue to authorize Jewish-only settlements in the West Bank. They built a “security barrier” which reaches far into the West Bank, and have instituted a system of separation between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank which many, including the UN, believe is similar to apartheid. Today, the Jewish population of Israeli settlements is nearing 600,000, and to believe that all these settlers could somehow be relocated from the West Bank just to accommodate Palestinian statehood is naïve.

Another serious issue which has doomed the two-state solution is the lack of strong, independent Palestinian leadership. Since the PA was established, there has been a power struggle between two prominent parties in Palestine: Fatah and Hamas. Although Hamas, founded as an Islamic resistance movement and long accused of being a terrorist group, won a plurality of seats in the Palestinian Parliament in 2006, Israel and its Western allies were not happy with the results and armed Fatah in the hopes that they would overthrow Hamas. As a result, Hamas seized full control of the Gaza Strip and was kicked out of the West Bank while Fatah and its leader, Mahmoud Abbas, gained control of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank. Since then, Abbas and Fatah have become more or less complicit with the occupation, with Abbas stating that he would let Israel keep all of its settlements should Palestine become independent and that his government’s cooperation with Israel in enforcing the occupation is “sacred.” Although Abbas did state in 2015 that his government was “no longer bound” to the Oslo Accords, this is largely a reflection of the facts on the ground since Israel has also failed to abide by the accords by refusing to hand over land to the Palestinians and intentionally driving a wedge between the West Bank and Gaza, threatening a two-state solution.

At one time, pushing for a two-state solution seemed to be the most just cause for both activists and states to pursue. The two-state paradigm had been the internationally recommended solution to the problem since the first partition plan was approved by the UN General Assembly in 1947. However, as the two-state solution proves to be less and less viable, many former proponents of the solution no longer support it out of a desire for justice for Palestinians. Instead, pundits argue that Israel cannot hold onto Palestinian lands because doing so would result in absorbing millions of Arabs and threatening Israel’s status as a “Jewish” state. To them, Palestinians and Israelis are fundamentally incapable of living with each other, and they must be separated at all costs to ensure a Jewish majority in Israel instead of giving the Palestinians what they are owed. In fact, when former Israeli PM Ariel Sharon forced the evacuation of all Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip in 2004, the reason was not a desire for peace but rather to “freeze the peace process” and ensure that Israel would not have to absorb the million-strong Palestinian population in Gaza that would certainly threaten the “Jewish state.” As the above facts show, while Trump did indeed acknowledge the death of the two-state solution, it does not mean he was the one who killed it.