Now that President Obama has signed the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014, the long-awaited Savannah Harbor Expansion Project (SHEP) has finally begun construction. SHEP is the byproduct of 17 years of negotiations by Congressmen, Senators, and Governors of both parties. Proposed as a response to the expansion of the Panama Canal, SHEP was spearheaded by former Congressman Jack Kingston of Georgia’s 1st District, Georgia Governor Nathan Deal, former Georgia Senator Saxby Chambliss, and Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, among others. The goal of the Savannah Harbor Expansion Project is to dredge the bottom of the harbor in order to accommodate larger container ships. These dredging efforts would increase the depth of the Savannah harbor from its current level of 42 feet to 47 feet, allowing larger ships access to the harbor. The project will also involve extending the channel’s entrance by seven miles and enlarging the Kings Island Turning Basin. Savannah is one of several different Atlantic ports responding to the Panama Canal Expansion Project with expansions of its own.

The expansion of the Panama Canal will allow for larger cargo ships to make their way from Asia, through the Canal, and up to the East Coast of the United States and to Europe. In response, many ports are vying to benefit from the increased business of these larger container ships. Ports all across the Atlantic – from Southampton and Liverpool in the UK to Miami, New York, and Charleston in the U.S. – hope to have their ports ready in time. The city of Savannah and many prominent Georgia politicians want to get in on the action. Unfortunately, a project of this magnitude will not be cheap.

The June 2014 price tag for SHEP came in at $706 million. Despite this price, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates that SHEP will bring $174 million in annual net benefits to the United States, a large part of which will go directly to Georgia’s government and businesses. It will allow for a 78 percent increase in the number of cargo containers brought into the harbor. As Mayor Reed put it, “This is the most consequential infrastructure project since Hartsfield-Jackson.” Beyond the actual dredging, the funding will go to preparing the harbor for expansion, including removing any sunken objects that may impede the progress of the project.

Now SHEP will finally see its time in the spotlight and, more importantly, in President Barack Obama’s budget. In his Fiscal Year 2016 budget, President Obama requested $29.7 million for the Savannah Harbor project. Of that request, $21.05 million will be for the actual construction and expansion project itself, with the remaining $8.66 million devoted to the disposal of the resulting waste in Georgia and South Carolina.

On top of President Obama’s budget request, the Army Corps has pledged an additional $21 million to the project from the Corps’ budget. While these commitments are impressive and have been well received by the Georgia Congressional delegation and Gov. Deal, it is a far cry from the project’s $706 million price tag, another $400 million of which is supposed to come in the form of federal funding. But it is a step in the right direction.

After all of the rhetoric, this story sounds like it has reached a happy ending. It is one of the greatest showings of bipartisanship in recent memory, especially among a delegation that Senator Chambliss described as being difficult to get to agree on “whether the sun rises in the morning.” SHEP has received support from all levels of government, including President Obama, who included it as part of his 2012 “We Can’t Wait” initiative. In October 2014, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Georgia Ports Authority signed a project partnership agreement to begin dredging, and the project officially began at the end of January 2015.

But, as is often the case with major construction projects, history has gotten in the way. Before the Army Corps can begin deepening the inner harbor, they must recover and salvage the CSS Georgia, a Confederate ironclad warship lying on the bottom of the Savannah Harbor. The Georgia was scuttled in the harbor in December 1864 in order to stop it from falling into the hands of General William T. Sherman and his rapidly approaching army. The CSS Georgia was forgotten by history as it lay dormant in the Savannah harbor, and it was only rediscovered during a 1968 harbor dredge. Although the Georgia never actually fired a shot in battle before it was sunk, she represents the evolution of naval technology and design during the 19th century.

The Civil War was arguably the first truly industrialized war, and the development of ironclads represented the importance of industrial capacities in warfare. The Georgia was part of a new era of naval warfare and a far cry from previous ships that relied on speed and elusiveness. The Georgia was just one of the ironclads designed and built during the Civil War. Its more famous cousins, the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia, were the two ships that met in the famous ironclad showdown at Battle of Hampton Roads.

Ironclads were built with a wooden hull, which was then plated with railroad iron or steel armor plates. These plates sometimes made the ships slow and unwieldy, as was the case of the Georgia, which was covered by 500 tons of railroad iron. The Georgia was so heavy that its steam engines were unable to propel it through the swift channel of the Savannah River. Because it could not serve as a seaworthy vessel, the Georgia settled into its role as a floating, shooting barge.

“It has very clearly become a symbol for why things went wrong for the Confederate naval effort,” said Ken Johnston, the executive director of the National Civil War Naval Museum. The Georgia is a microcosm of how things went wrong not just for the Confederate navy, but for the Confederacy as a whole. The Confederacy, which lacked the substantial industrial capability of the Union, plated 500 tons of railroad iron onto one ship that ended up being useless.

2015 marks the 150th anniversary of arguably the most trying moment in American history. The Civil War divided the young nation along sectional lines, and it left an estimated 620,000 Americans dead. September 2, 1862 – the Battle of Antietam – remains the bloodiest day in American history, as 3,654 Americans were killed in the course of the day. The Civil War, distant as it may seem to us 150 years later, is still a major part of American life today. Here in the South, it is not uncommon to see a car with a Confederate battle flag bumper sticker, and some states – including Georgia – have faced controversy regarding their current state flag’s similarity to the Confederacy’s own.

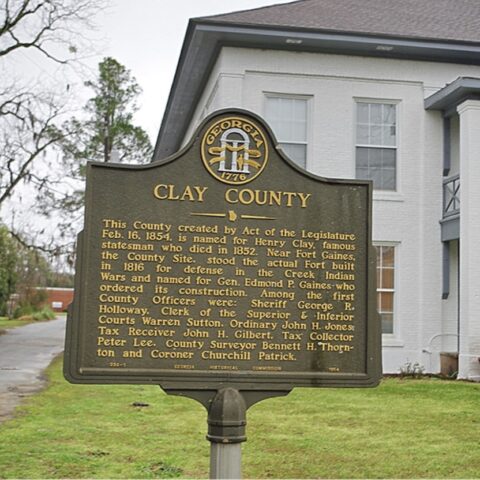

The Georgia is another example of how we live in a region and state constantly affected by our collective history, both good and bad. The Civil War, while in the past, surrounds us every day. The roadside markers of historical events may just be a blur as we drive past them, but they represent important moments in our state and country’s checkered past. It is fitting that the Georgia should see the light of day again on the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, reminding us all that history does not remain solely in the pages of textbooks. The Savannah Harbor Expansion Project will bring great economic opportunities to Georgia and the South at large, but it has already brought us one more great, sunken, and iron-plated link to our past.

Photo Credit: Builder Depot