by Frank Lumpkin, IV, J.D.

INTRODUCTION

Georgia has 159 counties, most of any state besides Texas, a state 4.5 times larger.[1] Of these 159 counties, forty-five have less than 10,000 residents and over a third lost population the last decade.[2] Studies reveal inadequate employment opportunities, insufficient education, ineffective law enforcement, and deficient healthcare access contribute to the shrinking of these counties.[3] Leaders proposed consolidating Georgia’s counties twice before, aiming to address these issues.[4] This article seeks to provide the history, legal basis, advantages, challenges, and solutions to county-county consolidation in Georgia to inform Georgians and their leaders about county consolidation so they can deem the necessity of consolidation.

HISTORY OF COUNTY-COUNTY CONSOLIDATION IN GEORGIA

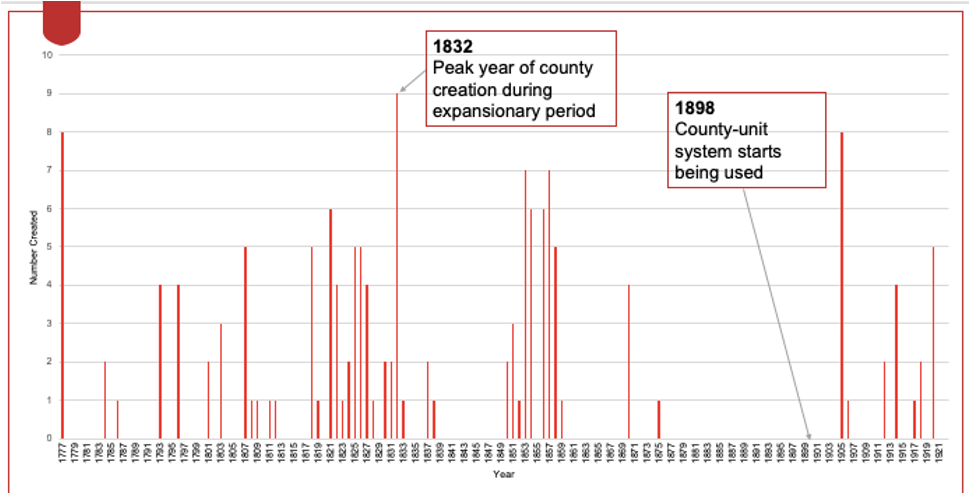

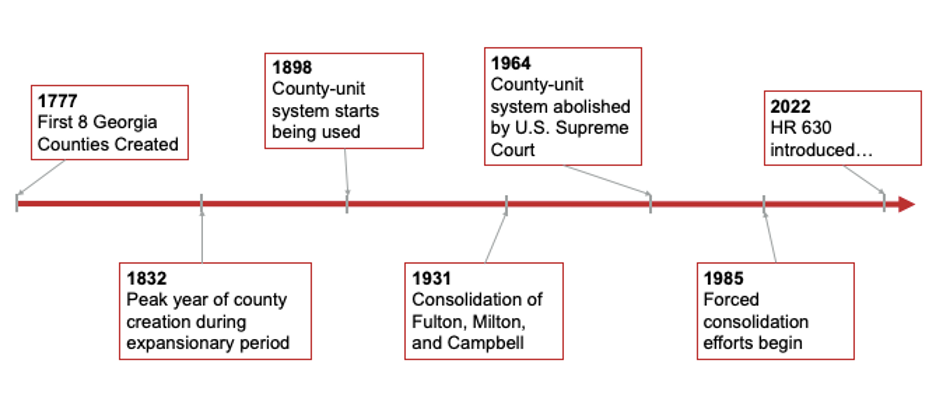

Before considering why Georgia should consider consolidating its counties, an understanding to why Georgia has so many counties must be established. Georgia has 159 counties for historical reasons embedded in geography, economics, and politics. Historians credit geography as to why Georgia has so many counties. Georgia folklore tells of a rule that county seats must sit no further than a “day’s mule ride away from any of its citizens”.[5] Though no law ever enforced county creation based on these parameters, the “mule ride” holds some truth.[6] During the 1800s and 1900s as Georgia expanded westward from the coast, the majority of citizens worked in dispersed areas in agriculture and few quality transportation options existed.[7] In an effort to provide its citizens with access to local government, Georgia created more counties. [8]

Besides geography, motivated by economics and politics, leaders also created new counties. Most counties formed as “peel-off counties” or counties created from the land of larger counties to jumpstart the economy in less developed areas of the state or to gain political power.[9] One newspaper said, “‘Give ‘em a courthouse and a separate school system and all the jobs that go with them.’ A piece of the pie if you will” in describing the economic boost generated through this county creation.[10] This economic boost was significant pre-1940 because jobs outside of agriculture were scarce and coveted in Georgia’s largely agrarian economy.[11] Those controlling these jobs held great power. One example of a person who used the creation of a new counties to harness power was Neil Gillis.[12] Gillis successfully lobbied the creation of Treutlen County so his real estate holdings were separate from the other counties and he could have increased influence over the new county government.[13] The family’s land holdings grew during the rest of the 1900s and Gillis’s son served as a state senator for the region.[14] For local economic and political reasons, county creation continued.

The “peel-off” movement accelerated when Georgia began implementing the county-unit system in 1898.[15] The county-unit system gave small counties a proportionately larger voice in state-level elections by assigning every county two votes, regardless of size.[16] The maximum number of votes even the largest counties could have was six.[17] Therefore, despite rural counties accounting for 32% of the state population, they controlled 59% of the vote.[18] Former Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge said, “I can carry any county…that ain’t got street cars” showing the strong influence the county-unit system had on state politics.[19] Twenty-three counties were added between the time the county-unit system was established and abolished.[20] Many counties followed this movement, the last being in Peach County in 1924.[21] In 1945, the Georgia Constitution capped the number of counties at 159.[22]

Today, changes in connectivity, urbanization, and a movement away from agrarianism has led to declining populations in rural counties, minimizing the power of those in control of these counties.[23] In addition, the “one man, one vote” decision by the 1964 U.S. Supreme Court [AD3] further clawed back economic and political power of county leadership.[24] Despite these changes, the creation of Fulton County in 1932 is the only example of county-county consolidation, which merged Campbell, Milton, and the previous Fulton county during the Great Depression to prevent bankruptcy.[25]

County consolidation was not considered seriously at the state level until state representative, Kiliaen Townsend, first in 1985 and second in 1990, proposed a plan to convert Georgia’s 159 counties into eighty-seven counties.[26] Townsend’s plan called for a constitutional amendment to institute these change, keeping the largest forty-two counties as they were while realigning the other 117 smaller counties into forty-five counties.[27] Townsend introduced the plan to the legislature twice but it failed to make it through committee on both attempts.[28]

TODAY’S CONSOLIDATION EFFORTS

While Townsend’s efforts in the 1990s could predict the fate of a modern consolidation effort, some members of the Georgia General Assembly remain undaunted.[29] In the 2022 session, Representative Darlene Taylor sponsored a resolution to create a Committee for Consolidation of County Governments and School Systems, which seeks to incentivize consolidation rather than mandate it.[30] Unlike previous attempts at consolidation, Taylor’s plan is sponsored by rural, Republican representatives, as opposed to solely urban representatives from the minority party.[31] The committee will include individuals outside the legislature to ensure comprehensive engagement with Georgia’s leadership impacted by consolidations.[32] The plan aims to give counties the means to consolidate on their own and offers incentives rather than obligations.[33] While previous attempts at consolidation were unpopular and dubbed “forced-consolidation,” Taylor’s more flexible plan presents a new approach that could have a greater chance of success.[34]

LEGAL FEASIBILITY

Precedent and a constitutional framework show consolidating is legally feasible. While uncertainty exists around what modern consolidation would look like, Georgia has past examples to draw upon. The consolidation of Fulton, Campbell, and Milton counties is most relevant, which required a two-thirds majority.37, 38 However, consolidation only requires a simple majority today. Legal challenges to this 1932 consolidation were dismissed in Hines v. Etheridge, upholding the constitutionality of consolidation and providing case law to prevent future challenges.[35] Modern examples of consolidation also exist in Georgia, with eight city-county consolidations.[36] While these consolidations used a different framework, they provide insight into how county-county consolidation might look regarding consolidating laws, constitutional officers, debt, tax collection, and county services. Overall, while consolidation is legally feasible, there may be legal challenges, and the specifics of a consolidation would depend on the counties involved and the terms of the consolidation agreement.

VARIETIES OF CONSOLIDATION

The same precedent legalizing consolidation shows consolidations do not take a single form.[37] This section addresses the different approaches to consolidating counties. Each approach is not mutually exclusive, but can be combined and used in a future consolidation. Approaches to consolidation differ in terms of legal implementation and government operation.

APPROACHES TO LEGAL IMPLEMENTATION: ORGANIC-CONSOLIDATION AND FORCED-CONSOLIDATION

Consolidating counties can be approached in namely two ways: organic-consolidation and forced-consolidation. Organic-consolidation involves following the legal process set forth by the constitution and precedent. [38] It requires passing a law for consolidation in the General Assembly and obtaining a majority vote in favor of consolidation in a local referendum in each consolidating county.[39] The consolidation law must also include a charter that outlines the terms of the consolidation, which is negotiated by a delegation of leaders from the consolidating counties. [40]

Forced-consolidation, which follows the Townsend approach, requires amending the constitution to give the General Assembly complete authority to determine which counties should be consolidated.[41] A constitutional amendment must pass by a two-thirds vote in the General Assembly’s House and the Senate. [42] It would then need to pass by a simple majority vote in a constitutional referendum. [43] If the amendment passes, the General Assembly could determine which counties should be consolidated. Laws would need to be passed to provide for the consolidating counties using the same procedure as for organic-consolidation.[44] While organic-consolidation follows a traditional legal process, forced-consolidation requires amending the constitution, which is more challenging. However, constitutional referendums in Georgia are not uncommon, as over 60 amendments have been adopted since 1983.[45]

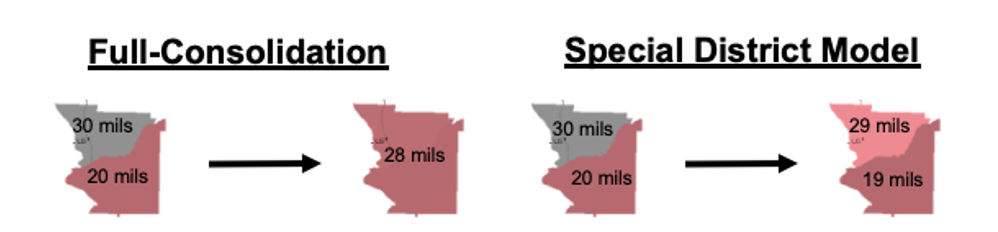

APPROACHES TO GOVERNMENT OPERATION: COMPLETE CONSOLIDATION AND SERVICE DISTRICT CONSOLIDATION[AD4]

Two approaches can be taken for operating the government in terms of allocating debt, collecting taxes, and providing county services: the complete-consolidation-approach and the service-district-approach. The complete-consolidation-approach combines all the dissolved counties’ debts into one collective pool. In contrast, the service-district-approach allows for debt to be maintained separately, different levels of tax to be levied, and distinctive services to be provided depending on where a citizen resides within the newly formed county.[46] Before counties dissolve and consolidate, they likely have different levels of indebtedness, tax rate, and county services. Rather than combining debt, altering the tax rate, and offering the same services, by using special districts, citizens of dissolved counties can become citizens of the newly formed county while still enjoying the tax rate and services before consolidation. Georgia’s three largest city-county consolidations utilized the service-district-approach.[47] For example, in the Columbus-Muscogee consolidation, the newly formed county has special districts made up of areas were within the old city-limits and then a general service district encompassing the entire county.[48] When the city and county were consolidated, debt from the city went to the special service districts while debt from the county went to the general service district.[49] Because the indebtedness is higher for the special service districts, the tax rate is also higher. The general service district provides a minimum level of services, while each special service district offers a higher level of county services.[50]

The service-district-approach works differently in a county-county consolidation than a city-county consolidation. Unlike a city, which before consolidation occurs, exists within the county, county-county consolidations bring together two geographically district territories. If counties consolidate using the special-district-approach, the general service district encompasses the entire area of the new county. This general service district takes on any new debt brought on by the county for county-wide expenditures, provide some minimum level of service, and levy a base tax rate for the administration of the consolidated county. Then, the areas within the territorial footprint of each dissolved county would be put into a special service district that retains the debt from the dissolved county, charges its own rate of taxes, and provides its own level of county services.

ARGUMENTS FOR CONSOLIDATION

Understanding that consolidation is legal in Georgia and the flexible approaches to consolidation, should consolidation efforts take place? The following sections explore the advantages and challenges of consolidation.

BENEFITS OF CONSOLIDATION

Proponents of consolidation argue that it will create more prosperous communities by gaining efficiencies and cost savings, enhancing planning capacity, addressing corruption, and providing greater representation for minority populations.

Efficiencies and Cost Savings

Some argue that consolidating counties could help struggling counties provide services more efficiently. Consolidation eliminates duplicate services, amalgamates facilities, and allows counties to purchase goods in bulk, resulting in significant cost savings. A study by Townsend in 1985 estimated that consolidation could save $1 billion in local and state taxpayer money, which, adjusted for inflation, is $2,266,036,725 today.[51] While this number represents the savings if nearly two-thirds of Georgia counties consolidated, which is unrealistic, cost savings from consolidation would still be significant.[52]

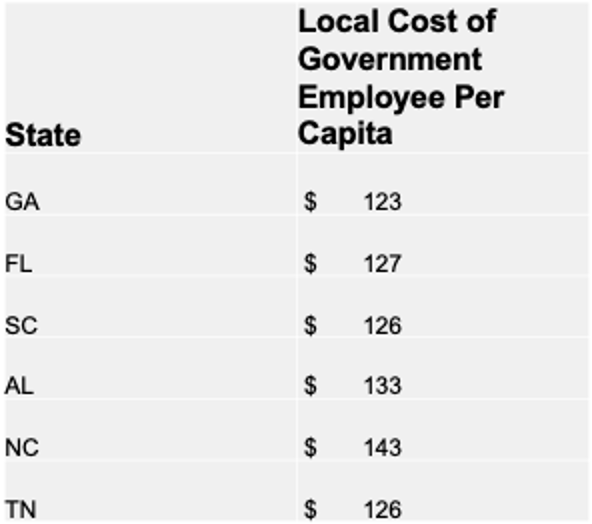

However, at the time of the Townsend study, Georgia had one of the most expensive per capita payrolls in the country, having nearly 600 state and local government employees per 10,000 people.[53] Times have changed though. Georgia is now operated more efficiently, having only 216 state and local government employees per 10,000 residents.[54] In fact, when looking at the total general expenses for running local governments in Georgia, Georgia spends less than any of its neighboring states, spending $123.46 per resident in 2020.[55]

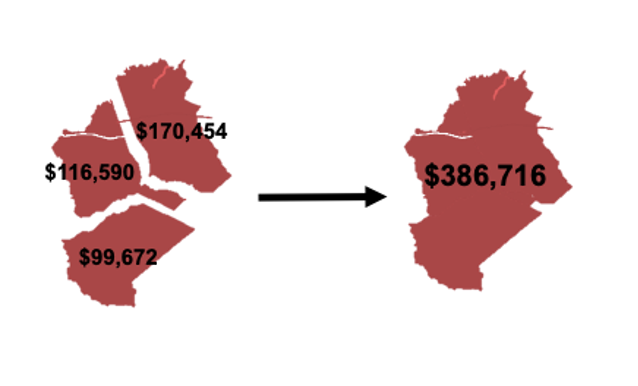

While some argue that this efficient governance reduces the need for consolidation, others claim that it could provide additional funds to improve the quality of services provided to Georgians. Georgia ranks thirty out of fifty in public safety.[56] Specifically, for violent crime and human trafficking, Georgia ranks tenth worst in both categories.[57] In terms of quality of public education, Georgia ranks thirty-six in the nation.[58] This especially impacts rural communities, where Georgia is positioned seventh worst in the country in quality of education provided to rural students.[59] Savings achieved from consolidation could improve these services counties deliver to their citizens. For example, consolidating payroll costs for administrative roles could allow consolidated counties to offer higher salaries and retain higher-quality candidates in education and public safety. For instance, the superintendents in Warren, Glascock, and McDuffie counties are paid $99,672, $116,590, and $170,454 respectively. Instead of paying these three salaries, the counties could combine these payroll costs and hire multiple teachers.[60] [AD7]

Consolidation also provides non-economic efficiencies. Larger school districts facilitate better quality education, as programs that are too small are limited in the interactions and advanced course work they can provide. A study by the Governor’s Education Review Commission determined that to facilitate quality education, a system needs at least 2,500 students.[61] David Lewis, superintendent of Muscogee County Schools bolsters these results, saying, “In a broad stroke, from efficiency and programmatic standpoint, there is benefit from scalability. Programs that are too small are limited in the advanced course work they can provide.”[62] Overall, consolidation has the potential to produce cost savings, economic efficiencies, and non-economic efficiencies.

Enhanced Planning Capacity

A consolidated county government has greater capacity to generate regional plans, rather than several individual government plans per region. A study on city-county consolidations in Georgia found that a single government can establish a single legislative agenda and speak with one voice in economic development, reaping all the benefits of such development.[63] For instance, rather than having two zoning boards, long-range planning can take place in one place. Leaders in Columbus-Muscogee saw this advantage, as they could respond to change better.[64] The single government was better prepared to address the rapid economic changes, and a county is apt to respond to grant and economic development opportunities because there are fewer elected officials to deal with. [65] Enhanced planning can be extremely valuable, as many of the issues facing rural Georgia are regional rather than confined to a single county.

Eliminating Corruption

Corruption cannot be completely eradicated, but consolidated governments offer more oversight through additional checks and segregated duties. Small governments are more prone to corruption due to their limited size and resources that impede oversight and enforcement mechanisms.[66] Georgia’s Constitution[67], statutes[68], and Attorney’s General[69] offer penalties and resources to prevent corruption, but absent a specific complaint about “egregious conduct” deemed important enough for officials to pursue corruption, an investigation will not take place.[70] [AD8] Consolidated governments provide higher transparency about the job performance of elected officials and prompt officials to take action when corruption occurs.[71] The prevention of corruption bolsters the government efficiency argument. A study determined if states with higher-than-average corruption had only the average amount of corruption, they would have spent 5.2% less over ten years.[72]

Greater Representation for Minority Populations

Studies suggest that minorities benefit from the consolidation of governments, as changes in government structure historically have given them more representation.[73] Recent consolidations around the country have resulted in many African-Americans being appointed or elected to regional administrative and legislative positions due to redistricting.[74] For example, after the Columbus-Muscogee consolidation, an African-American councilor was elected mayor, the first African-American to be elected to the position.[75] After the Macon-Bibb consolidation, African Americans made up a higher percentage of the new council-commission than before.[76] [AD9] Consolidation also gives minorities who did not have a voice in the charter-making process an opportunity to bring their concerns to the table.[77] Research finds African-Americans experience an increase in their “symbolic political representation” when minority representation is successful in a referendum.[78] Given their history of being excluded from office, consolidation can redress this grievance and benefit counties.

CHALLENGES

Several challenges exist regarding consolidation. County costs could increase in the short-term, local government might be wary to let go of their position, and citizens might have fears of losing local identity.

Initial Cost Increases

Creating a new government comes with start-up costs and, like any new initiative, comes with growing pains. Research shows cost savings from consolidation are likely attained only after one or several years.[79] Examples of start-up costs range from changing signage to equalizing salaries and benefits and integrating financial systems.[80] Without long-term vision, consolidation is a non-starter.

Local Government Wariness to Let Go of Their Power and Employment

Some local officials will not want to lose their power. Former Senator Floyd Hodgins said during Townsend’s consolidation effort, “Georgia must force counties to consolidate because…counties are never going to do it themselves”.[81] A more recent leader, former Columbus Mayor, Teresa Tomlinson, more optimistically, yet realistically states, “if you can get the elected officials with power and the money that backs them to support you, with education the community can be brought on board.”[82] Columbus-Muscogee proved this notion true after ten officials voted themselves out of a job under their consolidation plan.[83] Not every consolidation will have elected officials willing to leave their job though. For instance, while conducting research on consolidation in 1966, one researcher was bribed to cease his research in Wheeler County.[84] When the researcher failed to cease his work, the sheriff threatened him with jail time, showing the internal politics of consolidation.

In smaller Georgia counties, county government drives the economy, making some officials and citizens hesitant to relinquish power and jobs. While not every duplicate job is eliminated during consolidation, most higher-paying administrative roles are combined into one role.[85] In rural counties, the county manager, sheriff, and superintendent are the highest-paid positions, and local government jobs are often the only employment opportunities outside of agriculture.[86] For instance in Taliaferro County, county employees make up 24% of the labor force.[87] This strong dependence on county jobs makes some citizens resistant to consolidation, as it threatens their livelihoods.

Fears of Losing Local Identity

Not only are opponents to consolidation afraid of losing money, power, and profession, but of losing local identity. Looking back at Townsend’s attempt at forced-consolidation, fears of losing local identity were the most glaring challenges to consolidation.[88] One newspaper captures the extent of fear consolidation proposals ignited saying “logical as the [consolidation] amendment may seem to those who foresee more economic county government through consolidation, residents of counties which would be swallowed up into larger bodies will fight with a vengeance which would make World War II resemble a neighborhood skirmish”[89] With generations of family history and lives full of experiences, many citizens will be afraid to lose their county’s identity to a larger region.

PRACTICAL FEASIBILITY

Georgia’s economy and city-county consolidation within Georgia predict the feasibility of county consolidation. Forced-consolidation will likely fail to pass the legislature, as Georgia’s economy is now better off than during Townsend’s consolidation effort. However, Georgia’s successful city-county consolidations, with eight of the most in the country besides Alaska, show promise for county consolidation.[90] The success of Georgia’s county consolidation movement depends on a light-touch and collaborative approach like that set forth in H.R.630.

To ensure the success of county consolidation, the consolidation commission must educate citizens on the benefits of consolidation, tailor arguments to specific county needs, and collaborate with counties to establish a consolidation that works for all stakeholders.[91] The state should streamline the consolidation process and provide incentives for counties to consolidate, such as offering grants or awarding a percentage of saved funds to the first counties to consolidate.[92]

CONCLUSION

Consolidation is legally and practically feasible. Consolidation boasts many benefits like creating efficiencies and cost savings, enhancing planning capacity, addressing corruption, and providing greater representation for minority populations while also bound to face challenges such as short-term cost increases, pushback from local officials and employees, and fears of losing local identity. However, educating, collaborating, streamlining, and incentivizing elected officials and Georgia residents to support county consolidation is the best approach to a better future for their county.

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, Georgia: 2020 Census (2021); U.S. Census Bureau, Texas: 2020 Census (2021).

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, Georgia: 2020 Census (2021).

[3] Interview by Sheryl Vogt with Kilaen Townsend, former Ga. State Rep. (Nov. 17, 2006) [hereinafter Townsend Interview].

[4] H.R. 397, 138th Leg. (Ga. 1985).

[5] Jim Tharpe, Lawmaker wants to create Milton County, Atlanta J. Const (Feb. 16, 2010), https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/lawmaker-wants-create-milton-county/FqNOGQTg3ReiGSSpHajc4O/ [hereinafter Milton County].

[6] Stephannie Stokes, Why Ga. Has The Second Highest Number Of Counties In The US, WABE (Apr. 4, 2016) https://www.wabe.org/why-ga-has-second-highest-number-counties-us/.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Milton County, supra note 5.

[10] Donald E. Harwood, Keep County Merger Alive; It Makes Good Sense, Savannah Morning News, Feb. 14, 1985, at 1.

[11] William P. Flatt, Agriculture in Georgia, New Ga. Encyclopedia (May 25, 2004), https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/agriculture-in-georgia-overview/.

[12] Elizabeth B. Cooksey, Treutlen County, New Ga. Encyclopedia (Sept. 30, 2006),

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/treutlen-county/.

[13] Milton County, supra note 5.

[14] Id.

[15] Interview by Sheryl Vogt with Kilaen Townsend, former Ga. State Rep. (Nov. 17, 2006) [hereinafter Townsend Interview].

[16] Scott E. Buchanan, County Unit System, New Ga. Encyclopedia (Apr. 15, 2005), https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/county-unit-system/.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Ga. Hist. Soc’y, Eugene Talmadge, Ga. Pub. Broad (Dec. 9, 2013), https://www.todayingeorgiahistory.org/tih-georgia-day/eugene-talmadge/.

[20] U.S. Census Bureau, Georgia: 2020 Census (2021).

[21] Terry Dickson, County Consolidation Plan Gets New Attention, Brunswick News (Feb. 21, 2022), https://thebrunswicknews.com/news/local_news/column-perspective-county-consolidation-planit-gets-new-attention/article_857edccf-aa5c-5bc3-baa1-76f91fb27c25.html [hereinafter County Consolidation Plan Gets New Attention].

[22] Ga. Const. art XI, para II (1945).

[23] Telephone interview with Terry England, Ga. State Rep. (Nov. 2, 2022) [hereinafter England Interview].

[24] Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 554 (1964).

[25] 1929 Ga. Laws 251 (the law to consolidate Fulton and Campbell counties passed August 9, 1929, and consolidation was voted on and approved by Campbell County voters on February 17, 1931, and by Fulton County voters on April 22, 1931); 1929 Ga. Laws 551 (the law to consolidate Fulton and Milton counties passed August 9, 1929, and consolidation was voted on and approved by Milton County voters on February 17, 1931, and by Fulton County voters on April 22, 1931); State of Ga., Georgia’s Official Register 452, 472, & 492-93 (1931).

[26] County Consolidation Plan Gets New Attention, supra note 21; Proposal in House to Reduce Counties to 87, Ga. Cnty Govt. Mag., Mar. 1985, at 2.

[27] Kiliaen V. Townsend, Update For All Legislators (Mar. 7, 1990) [hereinafter Townsend Legislative Update].

[28] H.R. 397, 138th Leg. (Ga. 1985); 2 State of Ga., Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia at the Regular Session (1985); 2 State of Ga., Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia at the Regular Session (1990).

[29] England Interview, supra note 23.

[30] H.R. 630, 153d Leg. (Ga. 2022) (in the 2021-22 Session of the Georgia General Assembly, H.R. 630 made it through the House Committee on Governmental Affairs and was put in the House Hopper. HR 630 never made it to the House Floor for a full vote.).

[31] Townsend was a Republican from Buckhead in Democratically controlled Georgia. Further anger ensued from the fact neither county Townsend represented was a candidate for consolidation. County Consolidation Plan Gets New Attention, supra note 21; Townsend Interview, supra note 15.

[32] Id. (according to the resolution, the committee will be made up of three state House representatives, three state senators, the executive director of the Georgia Municipal Association, the executive director of the Association County Commissioners of Georgia, the executive director of the Georgia School Superintendents Association, the executive director of the Georgia School Superintendents Association, and two members appointed by the president of the Constitutional Officers Association of Georgia.).

[33] England Interview, supra note 23.

[34] Id.

[35] Hines v. Etheridge, 162 S.E. 113, 113 (Ga. 1931).

[36] 1977 Ga. Laws 3776 (Macon-Bibb consolidation); 1968 Ga. Laws 3571 (Columbus-Muscogee consolidation); 1997 Ga. Laws 4024 (Augusta-Richmond consolidation); 1979 Ga. Laws 3770 (Athens-Clarke consolidation); 1975 Ga. Laws 3617 (Cusseta-Chattahoochee consolidation); H.B. 1630, 147th Leg. (Ga. 2004) (Webster consolidation); H.B. 757, 148th Leg. (Ga. 2005) (Quitman consolidation); 2012 Ga. Laws 4575 (Echols consolidation).

[37] See 1929 Ga. Laws 251, but see 1977 Ga. Laws 3776.

[38] Ga Const. Art. IX § I para. II(c).

[39] Id.

[40] Ga Const. Art. IX § II para. I(c); R. Lucas, Types of County Government (2021) https://www.dekalbcountyga.gov/sites/default/files/users/user3566/RLucas_07.13.21_FINAL_Types%20of%20CouCou%20Government.pdf, [hereinafter Types of County Government] (the new charter must outline the government structure, specific powers, functions, essential procedures, and legal control of the newly formed county).

[41] H.R. 397, 138th Leg. (Ga. 1985); Ga Const. Art. IX § I para. II(c).

[42] Id.

[43] Id.

[44] Id.

[45] Initiative & Referendum Inst., Georgia (2022), http://www.iandrinstitute.org/states/state.cfm?id=31.

[46] Ga. Const. Art. IX § II para VI.

[47] Columbus, Ga., Code § 1-103 (2022); Macon, Ga., Code § 1-105 (2022), Augusta, Ga., Code § 1-7 (2022); Carl Vinson Inst. of Gov’t, A Review and Comparison of Georgia’s Three Largest Consolidated Governments 5 (2011), https://www.cviog.uga.edu/_resources/documents/publications/2011-georgia-three-largest-consolidated-governments.pdf, [hereinafter Comparison of Consolidated Governments].

[48] Columbus, Ga., Code § 1-103 (2022).

[49] Id.

[50] Id.

[51] Kiliaen V. R. Townsend, Update For All Legislators, Mar. 7, 1990. Fed. Rsrv Bank, Inflation, consumer prices for the United States (2022) (the dollar had an average inflation rate of 2.59% per year between 1990 and today, producing a cumulative rate of inflation of 126.60%).

[52] England Interview, supra note 23.

[53] Bill Shipp, Will Miller Go Dinosaur Hunting? Daily News, Feb. 3, 1990.

[54] Michael Maciag, States With Most Government Employees: Totals and Per Capita Rates, Governing (Mar. 21, 2014) https://www.governing.com/archive/states-most-government-workers-public-employees-by-job-type.html.

[55] Urban Inst., Georgia (2022) https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/projects/state-fiscal-briefs/georgia#:~:text=Per%20the%20US%20Census%20Bureau,between%20state%20and%20local%20governments.

[56] Crime & Corrections Rankings, U.S. News & World Rep. (2019) https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/crime-and-corrections.

[57] Samuel Stebbins, How the Murder Rate in Georgia Compares to the Rest of the Country, Ctr. Square, (Dec 10, 2021) https://www.thecentersquare.com/georgia/how-the-murder-rate-in-georgia-compares-to-the-rest-of-the-country/article_196234bd-2bdf-5099-be60-2170ff1382a5.html#:~:text=Though%20Georgia%20has%20a%20higher,to%20399%20per%20100%2C000%20natination; Human Trafficking Statistics by State, World Population Rev. (2022) https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/human-trafficking-statistics-by-state.

[58] Adam McCann, States with the Best & Worst School Systems, Wallet Hub (July 25, 2022), https://wallethub.com/edu/e/states-with-the-best-schools/5335.

[59] Daniel Showalter, et. al, Why Rural Matters 5 (2019) https://www.ruraledu.org/WhyRuralMatters.pdf.

[60] Telephone interview with David Lewis, Superintendent of the Muscogee County School District (Nov. 2, 2022); Townsend Interview, supra note 15.

[61] Townsend Legislative Update, supra note 27.

[62] Telephone interview with David Lewis, Superintendent of the Muscogee County School District (Nov. 2, 2022).

[63] Comparison of Consolidated Governments supra note 47, at 5.

[64] Id.

[65] Id.; The single government was better prepared to address the rapid economic changes, and a county is apt to respond to grant and economic development opportunities because there are fewer elected officials to deal with.

[66] Ctr. for the Advancement of Pub. Integrity, Fighting “Small Town” Corruption: How to Obtain Accountability, Oversight, and Transparency (2016), https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/public-integrity/files/fighting_small_town_corruption_-_capi_practitioner_toolkit_-_august_2016.pdf.

[67] Ga. Const. Art. I, § 2 para 1.

[68] Ga. Code Ann. §§ 36-30-4, 6, & 23 § 36-30-6, § 36-60-23; Ga. Code Ann. §§ 16-10-1—6.

[69] Off. of the Att’y Gen., Public Corruption, https://law.georgia.gov/public-corruption.

[70] Ctr. for the Advancement of Pub. Integrity, Fighting “Small Town” Corruption: How to Obtain Accountability, Oversight, and Transparency (2016), https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/public-integrity/files/fighting_small_town_corruption_-_capi_practitioner_toolkit_-_august_2016.pdf.

[71] Id.

[72] Alexandria Fisher, Study: Corruption Costs Taxpayers More than $1,300 Per Person, NBC Chi. (July 15, 2015), http://www.nbcchicago.com/blogs/ward-room/Study-Determines-Cost-of-Corruption-in-Illinois-267165861.html.

[73] K. B. Dankwa & T. Sweet-Holp, The Effects of Race and Space on City-County Consolidation: The Albany-Dougherty Georgia Experience, 247, 250 Urban Studies (2015).

[74] Id.

[75] Comparison of Consolidated Governments supra note 47, at 4.

[76] Mike Stucka, Macon-Bibb County consolidation wins with strong majorities, The Tel. (July 31, 2012), http://www.macon.com/news/politics-government/election/article 30109740.html.

[77] Tobe Johnson, Metropolitan Government: A Black Analytical Perspective, 1972, at 6.

[78] Id.

[79] Comparison of Consolidated Governments supra note 47, at 9.

[80] Id., at 9, 16.

[81] Jim Houston, Merging Counties Good Idea That’s Doomed, Ledger-Enquirer, Feb. 10, 1985, at C11.

[82] Telephone interview with Teresa Tomlinson, Former Columbus-Muscogee Mayor (Oct. 27, 2022).

[83] Comparison of Consolidated Governments supra note 47, at 3-4.

[84] Jim Galloway, Counties Have Grown Like Kudzu during Georgia’s History Apr. 28, 1995, at 13A.

[85] Townsend Interview, supra note 15; England Interview, supra note 23.

[86] England Interview, supra note 23; William P. Flatt, Agriculture in Georgia, New Ga. Encyclopedia (May 25, 2004), https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/agriculture-in-georgia-overview/.

[87] Ga. Dept. Labor, Georgia Area Labor Profile: Taliaferro County, 2021.

[88] Townsend Interview, supra note 15.

[89] County Consolidation Not A Popular Idea, Times-Enterprise, Feb. 9, 1985, at 4.

[90] National Association of Counties, Consolidated City-Counties (Oct. 27, 2021) https://www.naco.org/resources/consolidated-city-counties.

[91] England Interview, supra note 23; Telephone interview with Teresa Tomlinson, Former Columbus-Muscogee Mayor (Oct. 27, 2022); Citizens Research Council of Michigan, Government Consolidation: A Historically Unpopular Solution to Local Fiscal Strain (Oct. 23, 2020), https://crcmich.org/government-consolidation-a-historically-unpopular-solution-to-local-fiscal-strain.[92] Telephone interview with Teresa Tomlinson, Former Columbus-Muscogee Mayor (Oct. 27, 2022) (suggesting using an incentive); Comparison of Consolidated Governments supra note 47, at 5; Robin Toner & Jim Galloway, Pride Twarts County Mergers, Apr. 28, 1985, at 12A (another representative who supported Townsend’s plan suggested amending the plan to add incentives for consolidation); Ginger Gibson, Newt shoots for the moon Politico (Jan. 25, 2012), https://www.politico.com/story/2012/01/newt-shoots-for-the-moon-071991 (suggesting using an large monetary incentive to induce a certain action).