Amidst all the noise and headline-sensationalizing that has hijacked the economic news media since the 2016 election cycle, analysts at Goldman Sachs, America’s oldest investment bank, continue to offer insights that are equally refreshing as they are sobering.

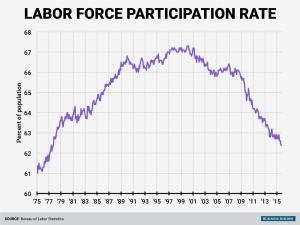

Last week, a note that circulated amongst the bank’s investors took a stab at explaining one of the economy’s most perplexing and under-reported figures: the labor force participation rate. Described as “the chart Obama-haters love the most,” the statistic, calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics since as early as 1948, accounts for the employed, the underemployed, and the actively-unemployed in order to get a better picture of how many Americans are truly engaged in the labor market.

In today’s hyper-partisan news environment, the metric has become a Rorschach test of political idealism, with pundits from both sides of the aisle using the metric as mere confirmation of their existing views on the economy. Over the last eight years, Republicans in Congress have continually cited the number as evidence of President Obama’s anti-growth policies.

Our current labor force participation rate, 62.9 percent as of February 3, is the lowest since the late 1970’s, when President Jimmy Carter was in office. The extent to which the Obama administration can be held responsible for this figure, however, has been disputed by economists across the country.

In Goldman’s note, research analysts pinned down the dismal statistic to three primary causes, all of which are presented through a decidedly-apolitical lens.

The first cause listed was “higher rates of painkiller use and middle-age mortality” that affects adults in certain parts of the country more than others. Alan Kruger, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor, released a paper last October claiming that 44 percent of prime-age, unemployed males had taken painkillers within the last 24 hours, “which is more than twice the rate reported by unemployed men.”

Indeed, the rise of opioid addiction in the United States has been well-documented since 1999, and we are now witnessing the economic repercussions of several years of political inaction regarding this epidemic. The Center for Disease Control reports that the number of prescription opioids sold in the United States has quadrupled since the turn of the century, despite no “overall change in the amount of pain Americans report.”

Another cause of the low labor force participation rates, according to Goldman Sachs, is the fact that “the U.S. incarcerates a much larger share of its population” compared to most other developed countries. This also makes it difficult for those convicted to find work once they’re released, leading many to give up altogether and disengage from the labor market, or, in the worst-case scenario, resort back to the criminal activities that led to their conviction in the first place. A study conducted by the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that almost half (49.3%) of federal prisoners were arrested again within eight years of their release.

The unreasonably-high incarceration rate in the United States is the result of many political and institutional failures that have been reinforced, rather than corrected, over the past several decades. Since Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs” began in 1971, for example, the United States prison population has more than quadrupled, led by the more-than-half of federal inmates who are locked up for non-violent drug-related crimes. Again, these policy failures are manifesting themselves in our economic data. With 724 people per 100,000 being held in prisons, the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, even higher than that of known authoritarian regimes such as Cuba and Russia.

Lastly, and most importantly, the New York-based bank speculated on the issue of automation in the labor force, a concern that many in the economic policy community are quick to point out should be at the forefront of consumer concern. While we’ve yet to witness the extent of the damage in our labor force, the future is looking increasingly bleak for a large portion of already-battered workers. A study conducted by University of Oxford economists Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne in 2013 found that 47 percent of workers in the United States held jobs that were at risk of being wiped out due to advances in technology and automation.

To help protect the interests of the U.S. labor market, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates recently suggested a “tax on robots” that he expects would curb the effects of negative economic externalities brought about by automation. Like carbon emissions or tobacco consumption, new technology creates tangible economic benefits for big business, but it comes at an increasingly-contentious social cost. Gates’s proposed tax may have the desired effect of slowing down structural unemployment, but many in Silicon Valley fear it will create a culture where innovation is discouraged and technological stagnation becomes the status quo.

When factoring in these economic barriers, it becomes even less clear who is to fault for our unimpressive labor force participation statistics. The real ‘fake news’ of our generation comes not from CNN, but from policymakers who repeatedly peddle false-causation of economic data for political gain, while ignoring the many glaring institutional failures that are far more likely attributable to our economic shortcomings.

Regardless of where to place the blame, however, the necessity of bringing these workers back into the labor force has become increasingly vital to the agenda of the Trump administration, along with the well-being of our economy in general. In regards to President Trump’s proposed $1 trillion, 10-year infrastructure plan, just to provide one example, the math simply doesn’t add up without it. To maintain current levels of labor productivity in the construction industry, over 570,000 new workers would need to be added before the plan could come to fruition. At the peak of the U.S. housing bubble, when supply-side workers flooded into the industry to help offset record-high consumer demand, only about 500,000 new jobs were added annually. The clear alternative here for most developed countries would be to rely on immigrants or refugees to fill in the blanks, but for a president who described deportations as “a military operation,” that option seems unlikely.

In short, it is not factual or practical to blame historically-low labor force participation on the Obama administration, or any other single administration for that matter. A large variety of factors have led us to this point, and it will likely take several four-year-term’s worth of sensible legislation to bring these workers out of the shadows. Before we can Make America Great Again, we must first make America work again.