By Eli Watkins

“There’s a special kind of nerd though, who thinks computers will overtake mankind in thirty years, changing humanity in ways incomprehensible to us now, ignoring the third of the world without electricity. So the singularity is the nerd way of saying, ‘In the future, being rich and white will be even more awesome.’ It’s flying car bullshit: surely the world will conform to our speculative fiction, surely we’re the ones who will get to live in the future. It gives spiritual significance to technology developed primarily for entertainment or warfare and gives nerds something to obsess over that isn’t the crushing vacuousness of their lives.”

– John Campbell, Pictures for Sad Children

Depending on where you stand on the political spectrum, the coming tumultuous phase of the economy may or may not be logically expected. Regardless, it has begun already. New technology is displacing workers, as it has for centuries, but this time around, some of those workers are not able to transition to different fields. Creative destruction may already be raising the natural rate of unemployment, and it almost certainly will in the years to come. A significant portion of the population will become unemployable, akin to the tools of a bygone era.

Look at things now. A cashier is a touch screen. A taxi company is a mobile app. A researching team at a law firm is an algorithm. The Associated Press has bots writing some sports and business stories. AOL is laying off advertising staff as it transitions to “programmatic” advertising. There is a bot on Tumblr that reviews art and another that buys drugs off the darknet. Smarter technologies will uproot entire industries, increasing efficiency and eliminating employees.

It is relatively easy to see how machine learning and robotics will work their way further up the ladder too. People would be less likely to hire a lawyer when they can talk to Siri, Attorney at Law. They might pass on consulting financial experts when some software can give them instant advice. Maybe in the not too distant future people will look back in horror that they ever trusted another human to diagnose their illnesses. This might all be unsettling enough without even considering the possible machine-led disruption of human relationships, physical and emotional components included.

But if people do not like the sound of all of this technology-driven change, what can they do? The rejection of revolutionary technologies would be utter luddism. How could one logically turn down say, an infallible and infinitely less expensive team of surgeons just because it happened to be a team of robots? Would you want to say no to the end of car crashes or any of the other frequent tragedies caused by human errors? Clearly not, unless you happen to be a member of one of the United States’ many fringe militias or a religious sect.

That is not to say there are no credible people who are skeptical of machine learning and the like. Many people, including Elon Musk and Bill Gates, have expressed concern over technologies approaching the “singularity,” a term for the theoretical point where the capabilities of artificial intelligence surpass human intelligence. But even people like Musk and Gates are not stopping the coming onslaught of technological progress. Musk recently donated $10 million to an institute intent on making artificial intelligence beneficial to humanity. Gates’ company Microsoft is reportedly working on a “personal agent,” an artificial assistant that keeps track of users’ lives for them.

So, it does not look like people will reject technological revolutions wholeheartedly. In the face of a crisis of widespread and permanent unemployment, society will instead have to adapt. Interestingly, there are two causes from the political Left that could allow a capitalist system that is innovating its way beyond people to adapt and survive. They are universal healthcare and guaranteed basic income. Universal healthcare is a term for any government-funded program dispensing medical care, as needed, to all people, free of charge. Guaranteed basic income is somewhat less well known, but it is certainly growing in prominence. It describes a government-funded program that gives money to all people, at levels high enough to live off, regardless of employment status. Crudely put, it is something like über-welfare.

To many people in this country, these ideas are radical. They constitute socialist fantasies that will kill people’s drive to work hard (or work at all), send deficits soaring and raise taxes to the point they become an overwhelming burden for high-earners. Depending on how one sees it, and how the government would actually institute these programs, those concerns might be entirely valid. Look at Europe. European countries have much stronger welfare states than the United States does as well as universal healthcare programs. The European economy is also much weaker than ours is. Now, those government programs are probably not the reason for European stagnation. Since the crash, Europe has suffered a combination of austerity measures and timid central banking practices. That combination, alongside a continued struggle with a monetary union that maybe should never have existed in the first place, seems like a larger problem for Europe’s economy than healthcare and welfare, but it is still possible that generous social programs have weakened the European economy.

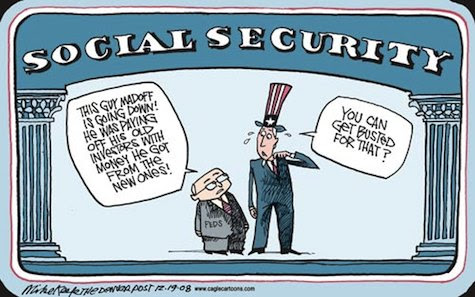

Bearing these concerns in mind, we can actually look to a certain section of the United States, instead of Europe, to get a better idea about how these two massive social overhauls would work. Look to the elderly, the recipients of two of the largest socialist giveaways on Earth: Medicare and Social Security. These two programs, taken together, comprise a plurality of the federal budget. They are also programs that both political parties ostensibly cherish. In an era of deep political polarization, where both parties have no ideologically overlapping elected members, both parties have long since conceded that the government has a role to play in guaranteeing healthcare and a basic, albeit modest, income for the elderly.

Of course, one can see these programs as the fair exchange the government makes with its retirees for a lifetime of working and paying taxes. But to some extent, or at least in plenty of instances, this is a false picture. What is more, the retirement age is to some extent an illusory boundary, an arbitrary point the government has designated as the point where benefits kick in. Over the course of the 20th century, it came to be that the government offered these benefits to the elderly, and the programs stuck. Now, we simply take it as a given that upon reaching a certain age people in the United States have a right to healthcare and a basic income. Perhaps it is time to remove the age threshold.

The engine of the economy requires all people to earn money and spend money, especially in this country, which relies on consumer spending more than many others. If new technologies raise the natural rate of unemployment to levels that are currently unthinkable, the United States will need a way to facilitate economic growth. If the average person, from an average background, with average educational attainment and skills, cannot rely on his or her job to provide healthcare, then something will have to fill the void or there will be the kind of health crisis this country does not currently have a way to manage.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the main welfare program in the United States, lasts only for a brief period and requires employment activity. Without major reform, it cannot be enough to allow people to afford their basic needs, let alone spend enough to keep the economy running. TANF is not designed for permanent and widespread unemployment. Moving on to healthcare, one cannot reasonably assume Medicaid will expand to the gradually uninsured multitudes. Take note of how swimmingly the current, relatively small, Medicaid expansion is going. Moreover, both TANF and Medicaid have a begrudging tone to them and do not enjoy the overwhelming support Medicare and Social Security do.

Maybe that is because Medicare and Social Security are much larger and more deeply engrained in a more politically empowered section of society than TANF and Medicaid. Or, maybe the programs are popular because they simply work. The elderly of the United States are living longer. People love Medicare. By many measures, it is a program that meets its goals, albeit at a hefty price. People love Social Security too. It turns out that a program that consists of putting checks in the mail is very popular. For some time now, politicos have referred to Social Security as the “third rail of politics.” It is a program so holy and so beloved, that even mentioning changing it can kill one’s political career. So, members of both parties tend to talk about Social Security with all the fear and deference afforded to the God of the Old Testament.

Ironically, the happy recipients of these programs are also the nation’s most conservative voting bloc by age. Elderly voters would likely lean against universal healthcare and guaranteed basic income. And yes, much of that opposition might be grounded in very real concerns about taxation and radical changes to society. But let us face it, we are about to enter a period of uncertainty and overwhelming technological expansion. Many people, in terms of employment, will simply become unnecessary, including–and perhaps especially–the occupants of some of the highest paying jobs.

Thanks to these technological changes, our future could be truly amazing. We could develop a power source that provides virtually unlimited, clean energy. We could end the process of aging and disease. We could flip the switch on a machine that independently discovers boundless knowledge. We could point at some speck in the night sky and say, “Remember when we went there?” Maybe some of us will actually live to see one, or all, of these things happen. But we have to make sure, one way or another, that in our race to the future we do not leave ourselves behind.