“My administration shall respond in the severest way possible to the attack and any other attack to us.”

Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta responded fiercely to the terrorist attacks on Garissa University College early on the morning of April 2. The Islamist, al-Qaeda-affiliated organization al-Shabaab claimed credit for the assault in which attackers killed at least 147 people, including 141 students, and injured 79 more. In a statement on social media, al-Shabaab stated that because of the 2011 Kenyan invasion of southern Somalia, “Kenyan cities will run red with blood.” However, due to a history of overly harsh counterterrorism measures by the Kenyatta administration and a promise to “respond in the severest way possible,” it is unclear whether Kenyan cities will be sanguine from blood on the hands of the Kenyan government or on the hands of al-Shabaab terrorists.

This is not the first al-Shabaab attack in Kenya, despite the fact that the group has its origins wholly in Somalia. Over the last three years, al-Shabaab has killed at least 400 people and injured over 1,000 more in Kenya. Its recent fixation on Kenya stems from the invasion of southern Somalia by Kenyan troops in Operation Linda Nchi in October 2011. After al-Shabaab lost the strategic port city of Kismayo the organization’s shrinking territorial control has forced it to launch increasingly risky attacks into Kenya to maintain visibility and legitimacy. The most notable of these was the 2013 attack on the Westgate mall in Nairobi, where 67 were killed. Other instances of terrorist violence have driven non-Muslims out of northeastern Kenya such as the November 2014 attack on a bus travelling to Nairobi that killed 28 and the mass execution of 36 Kenyans near the Somali border.

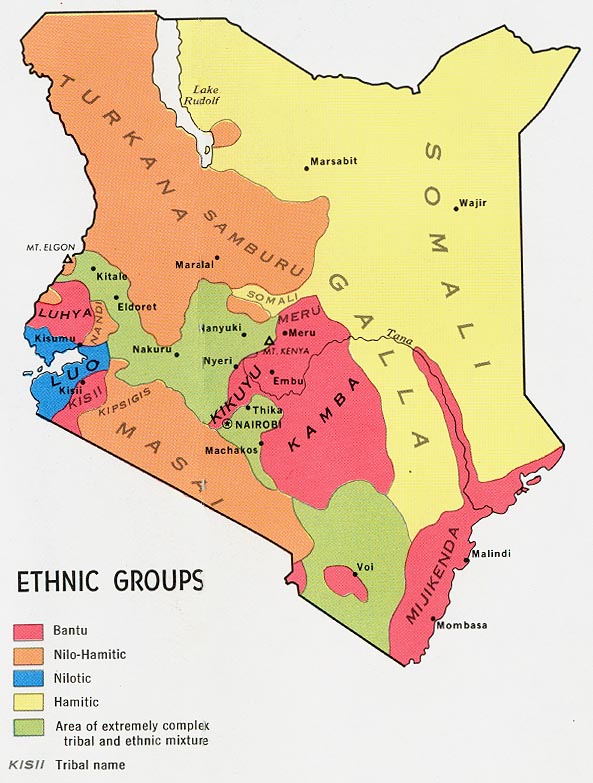

The exodus of non-Muslims in northeastern Kenya has turned the area into a fertile breeding ground for al-Shabaab recruits. Moreover, socioeconomic marginalization of Kenyan Muslims, who comprise 10 percent of the country’s population, has set the scene for the opportunistic power grab of al-Shaabab in northeastern Kenya. While only 30 percent of the people in the Central Province, the agricultural heartland near the capital of Nairobi, live below the poverty level, 74 percent of residents in the northeast live below the poverty line. Additionally, access to medical resources is similarly skewed; there is one doctor for every 20,715 residents in the Central Province compared to only one doctor per 120,823 residents in the northeast.

This stark contrast in living conditions is intertwined with religious undertones. Because inland Kenya is predominantly Christian, and the coast and hinterlands are decidedly Muslim, Kenyan Muslims feel as if they are pushed to the margin by the centralized Christian-friendly government. Al-Shabaab capitalizes on these religious tensions in order to bolster its recruitment and develop a foothold outside of its presence in Somalia.

Ripe with already tense religious relations, Kenya’s Muslim population is increasingly susceptible to the radical teachings of al-Shabaab thanks to President Kenyatta’s ethnically – and religiously – charged counterterrorism policies. Although eight of the most egregious provisions of a contentious security law were overturned by the High Court at the beginning of this year, this recent event belies a larger narrative of scrapping constitutional provisions for the sake of heightened internal security. Kenyatta’s questionable policies began with 2013 passage of laws following the Westgate attack intended to limit the expression of media outlets with regards to terrorism, and following an Al Jazeera investigation on the topic, the government arbitrarily banned over 500 NGOs from Kenya for charges ranging from “mistakes in their paperwork” to abetting terrorism.

The suppression of civil society has granted the administration and its security and police officers more leniency in superseding the rights of its citizens, particularly those of Muslims and ethnic Somalis. For instance, in response to an incre ase in terror plots in Nairobi, Kenyan authorities arrested over 4,000 Muslims without knowledge of their crime. This scapegoating of Muslims and Somalis has become a rallying cry for al-Shabaab recruiters. Moreover, there have been numerous instances of extrajudicial killings and police brutality toward Muslims. In the past year, the coastal city of Mombasa has witnessed many drive-by police killings of radical clerics, and the beating of children and elderly people outside a Mussa mosque last February has furthered the divide between Muslims and the government.

ase in terror plots in Nairobi, Kenyan authorities arrested over 4,000 Muslims without knowledge of their crime. This scapegoating of Muslims and Somalis has become a rallying cry for al-Shabaab recruiters. Moreover, there have been numerous instances of extrajudicial killings and police brutality toward Muslims. In the past year, the coastal city of Mombasa has witnessed many drive-by police killings of radical clerics, and the beating of children and elderly people outside a Mussa mosque last February has furthered the divide between Muslims and the government.

Lastly, even Somali refugees along Kenya’s northern border are being targeted and stripped of their civil liberties. Last year, these refugees were banned from working in neighboring towns and were required to permanently remain in refugee camps, simply because of their ethnicity. All of these policies, although presumed to being fighting the spread of al-Shabaab into Kenya, are facilitating the spread of al-Shabaab by providing conditions in which Muslims and ethnic Somalis are marginalized. The marginalization and accusatory nature with which the government treats these groups, in fact, may be one of the strongest reasons that al-Shabaab develops a stable base in Kenya.

In light of al-Shabaab’s rapidly decreasing support and territory in Somalia, the Garissa University College attack last Thursday represents an overtly desperate strategy of launching bolder attacks in Kenya to try to gain recruits in the border and coastal regions. And the overeager behavior of Kenyan security and police officials is playing into the hands of the terrorist organization. The parading of the dead attackers’ corpses through the streets of Garissa is likely to undermine the legitimacy of government officials and give merit to the accusations heaped on the Kenyatta administration of corruption and religious bias.

This reinvention strategy has been debated by counterterrorism experts, but it is likely that if the Kenyatta administration continues its unconstitutional counterterrorism regime, then the foothold of al-Shabaab in Kenya may become entrenched. In order to counter the facilitation of radicalization by marginalizing Muslims and ethnic Somalis, it is in the strategic interests of the Kenyan government to engage Muslim communities, affirming that they are part of the solution to radical extremism in Kenya and not assumed to be part of the problem.

– By Eli Scott