By: Garrett Herrin

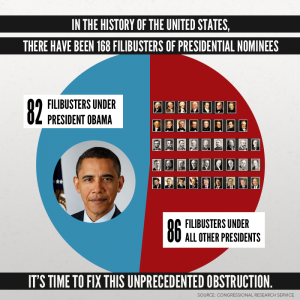

In a graphic posted to U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s (D-Nev.) Twitter account on the day of a historic vote on filibuster reform, the senator writes that, “In the history of the United States, there have been 168 filibusters of presidential nominees: 82 blocked under President Obama, 86 blocked under all the other presidents. It’s time to fix this unprecedented obstruction.” (The graphic scored a “mostly true” Truth-O-Meter rating by Tampa Bay Times’s PolitiFact; see the analysis here.) On Nov. 21, 2013, the U.S. Senate exercised the “nuclear option” in a 52-48 vote with all but three Democrats backing the move and every Republican opposing it, amending chamber rules so that a simple majority of senators is needed to invoke cloture and move to a confirmation vote on executive and judicial nominees (save for those to the U.S. Supreme Court).

The New York Times heralded the vote in a November 21, 2013, editorial:

For five years, Senate Republicans have refused to allow confirmation votes on dozens of perfectly qualified candidates nominated by President Obama for government positions. They tried to nullify entire federal agencies by denying them leaders. They abused Senate rules past the point of tolerance or responsibility. And so they were left enraged and threatening revenge on Thursday when a majority did the only logical thing and stripped away their power to block the president’s nominees.

Because only a simple majority is needed to amend most parliamentary rules changes, the majority could have scrapped the filibuster at any point and made the Senate more akin to the House of Representatives operationally. The stakes of losing the filibuster were—and still are (for what remains of it)—incredibly high: the majority party of today will almost certainly be the minority party in the future. The filibuster provides leverage for the minority, and losing it means the minority effectively has zero power in a polarized era.

Although the recent filibuster changes only apply to executive and judicial nominees, they may lead to a domino effect, eventually leading to the total elimination of the filibuster for both Supreme Court nominees and for legislation. The Washington Post writes that Republican leaders suggested after the November 2013 rules change that they may vote to repeal the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act by a simple majority were they to win control of the Senate in 2014, suggesting the new majority would eliminate the legislative filibuster. Even Majority Leader Reid said in a January 2014 appearance on CBS’s Face the Nation that he has not eliminated the possibility of Senate Democrats scrapping the filibuster altogether, although it is unlikely that there presently exists enough support in his caucus for such a change.

Last November’s filibuster rules change may be consequential for presidential nominations, but it does not scratch the surface of the minority party’s systematic advantages on governance in the United States. Al Jazeera America points out that a majority of the U.S. population lives in only 10 states, meaning the majority of the population receives 20 percent of votes in the Senate, while the minority receives 80 percent. The system of Senate apportionment is written into the Constitution and will almost certainly remain in place, if only because of the scant likelihood of any systematic reform moving through the amendment process. While Senate malapportionment is well-understood and perhaps a more appropriate topic for a high school civics class, we should not pretend that filibuster reform represents a “return to democracy” (as the headline of The New York Times editorial suggests) when the ‘one person, one vote’ principle is already so remarkably violated.

In November, Republicans will attempt to gain a Senate majority and maintain their House majority. The latter mission seems very probable according to a group of political scientists at George Washington University, who use a forecasting model to determine the likelihoods of majority outcomes: in their House model, they predict that Democrats have a one percent chance of winning a majority. In their Senate model, however, they predict that Democrats have a 56 percent chance of retaining their majority. But when the model is adjusted to only include midterm elections since 1980 as a predictor variable, Democrats have a 36 percent chance of retaining their Senate majority (see their predictions via The Washington Post for the House and the Senate).

There is a very real chance that Republicans will control both chambers of Congress come January 2015, and with it, a chance that four decades of the 60-vote supermajority rule may come to an end. If this were to occur, not only would it would spell doom for Barack Obama’s chances to advance his agenda in the final two years of his presidency, but it would also mean that a short-term fix for Democrats’ present frustration could result in a permanent change in the legislative process. Whether this change ultimately benefits one party over the other in the long term remains to be seen. If Republicans follow through with their warning that they may fully eliminate the filibuster when they achieve a majority, Democrats will have little room to complain given they are partly responsible for provoking the change in the first place. Even if Democrats retain their majority, it is only a matter of time before the filibuster is eliminated entirely. Regardless, gridlock will likely continue in Washington until divided government ends and one party controls the House, the Senate, and the presidency.