By: Rachael Zipperer

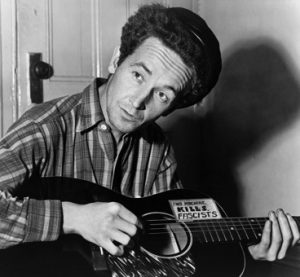

In 1940, Woody Guthrie wrote “This Land is Your Land,” probably his most popular song and arguably one of the most influential songs in American folk music. The song has been covered innumerable times over the decades since it was written, and Guthrie inspired artists like Bob Dylan who have gone on to create some of the most recognized and well renowned music of the century. Legend has it that Guthrie wrote the song in response to hearing “God Bless America” one too many times and that he intended “This Land is Your Land” to carry a Marxist (or at the very least Populist) message against the ideal vision of America in songs like “God Bless America.”

Taking this into account, as well as the influence Guthrie had on political musicians like Dylan, it seems that the evolution of the American protest song can be traced back to “This Land is Your Land.” At this point, however, it is difficult to see Guthrie in modern examples of political music.

More recently, Conor Oberst, the front man and creative force behind the folk-rock project Bright Eyes, reunited with his lesser known band Desaparacidos to write a protest song for the modern age. While Bright Eyes often addressed concerns about the Bush administration, perhaps most notably with 2005’s “When the President Talks to God,” Oberst claims he does not enojy being political. However, he has recently made immigration law his political cause.

In 2010 Oberst put on a 14 band benefit in his hometown of Omaha to raise awareness about immigration issues. During a Bright Eyes show at Athens’ own Georgia Theatre in the Fall of 2011, Oberst took over two minutes between songs to address the audience directly concerning immigration laws. He referred multiple times to strict immigration laws as “the new Jim Crow,” citing the infamous rizona bill as well as bills passed in Alabama, Oberst’s own Nebraska, and HB 87 in Georgia. Amidst cheers from the front rows, Oberst called for action and awareness from the Georgians in attendance.

Desaparacidos’ song “Marikkkopa,” is a result of Oberst’s devotion to this cause and is overtly political in its attack of Arizona’s SB 1070 and Joe Arpaio, the Sheriff who carried out the law to the extreme. The title links the name of the county, Maricopa, in which Joe Arpaio is Sheriff, to the comparison some dissenters have made between Arpaio’s actions and the actions of the Jim Crow era Ku Klux Klan (KKK). The song ends with a sound byte from an interview with Arpaio in which he claims it was “an honor” to be compared to the hate group.

Another band, Arizona’s own folk-punk duo Andrew Jackson Jihad (AJJ), also tackled the issue. They, like the Oberst side project, attack Joe Arpaio by name with their punk tribute “Joe Arpaio is a Punk.” While many of the band’s other songs are predominantly acoustic and folksy, this song focuses on the “punk” aspect of the folk-punk genre. Diverging from previous songs that “ripped off…Woody Guthrie,” this protest song takes the music and some of the lyrics from punk classics “California Uber Alles” by the Dead Kennedys and “Last Caress” by The Misfits as the base for this song protesting the actions of the Maricopa County Sheriff.

Though both Oberst and AJJ have roots in folk music, the punk tone of “Marikkkopa” and “Joe Arpaio is a Punk,” make these protest songs angrier and more violent than the peaceful protest songs that occurred in folk music from Guthrie through the 60’s and beyond. This kind of emotion can rile up an audience, but the specificity of “Marikkkopa” and “Joe Arpaio is a Punk” may make their impact short lived, if it was not too late to begin with. Both of these songs were officially released in late Summer last year, after the Supreme Court decision to strike down many provisions of the Arizona law and after the ACLU took legal action against Joe Arpaio. Both address

only the Arizona law, specifically Maricopa County and Arpaio, using his and the county’s names and samples from actual interviews with “Sheriff Joe.” So, once the American government and public has addressed these specific issues, will the songs have any place in our culture?

Part of the reason “This Land is Your Land” has not faded into obscurity seems to be its timeless and universal message. Unlike the two examples of contemporary protest songs, it makes no reference to its time’s current events or to any specific issue. The tone of the song is also one of unity rather than anger. Though the more radical verse that describes hungry people in the “relief office” and questions “was this land made for you and me?” is an obvious indicator of the song’s intent to question government practices, as a whole “This Land is Your Land” focuses on the positive, embracing qualities of America to the point that it is often considered a patriotic song above being thought of as a protest song.

Though modern political songs have found their cause, their message does not seem likely to withstand the test of time. This implies that while “This Land is Your Land” will likely remain part of American culture for many years to come, the spirit behind the song that sought a positive societal shift rather than aggressive action against single issues may be lost.