Justice Anthony Kennedy may not be the United States’ poet laureate, but he brought out his best prose for the majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, the recent Supreme Court case which declared same-sex marriages to be protected by the Constitution.

“[The same-sex couples’] hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions.”

“No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family.”

“Rising from the most basic human needs, marriage is essential to our most profound hopes and aspirations.”

Many praised Justice Kennedy’s opinion. Social activists, businesses, media, and even the White House celebrated the decision in an appropriate rainbow fashion. Kennedy’s elegant prose was often front and center in the celebrations. His words captured what many Americans already believed: Homosexuals are equal citizens and no less worthy of the institution of marriage than heterosexuals. The Twitter hashtag “LoveWins” soared in the days following the decision and created a feel-good sense of American pride for many supporters of same-sex marriage.

But was this case really about love? That question is far more complicated than the enthusiastic response of same-sex marriage supporters on social media would have you believe. In reality, the emotional issues of love and commitment were overshadowed by complex legal jargon. Justice Kennedy may have sprinkled his opinion with flowery musings about the importance of family and having a companion to venture into the unknown with, but the crux of his argument was concerned with controversial questions about constitutional interpretation and democracy. These issues have implications far beyond same-sex marriage.

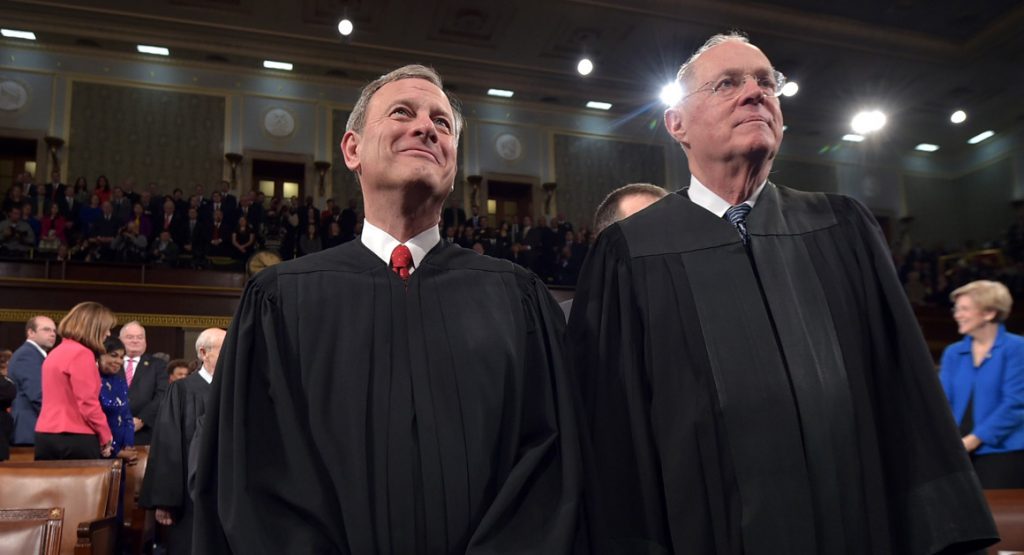

Juxtaposing Kennedy’s majority opinion with Chief Justice John Roberts’ dissent reveals a much broader problem than marriage equality: the conflict between justices declaring implied constitutional rights and voters enacting their will through at the polls. Rights protected by the Constitution are supposed to be so important that they are declared off-limits in the political process. When justices interpret the Constitution as having additional unenumerated rights, voters lose power to decide public policy.

Kennedy’s analysis of court precedent identifies four major principles inherent in the right to marriage.

1) Being able to marry who you want is essential to the idea of individual autonomy. Determining one’s own destiny is so important that the state should not be able to interfere. This is consistent with the logic of Loving v. Virginia which struck down bans on interracial marriage.

2) Marriage creates a two person union that is unlike any other in its importance to committed individuals. It allows the public expression of a personal bond that was determined to be vitally important in past cases such as Griswold v. Connecticut.

3) Marriage safeguards children and the integrity of the family. In Zablocki v. Redhail, the court said that having a home and raising children were central to liberty. Families benefit from the stability and positive stigma that marriage creates.

4) Marriage is the building block of American society. The fundamental role of families is the reason why marriage is subsidized by the state and given special privileges. These privileges include tax benefits, property rights, spousal privilege in medical facilities, and the right to contest child custody.

If these principles define the right to marriage, Kennedy finds no reason why homosexuals should not be included. If homosexuals are equal under the law, then they should also be able to marry whom they choose, engage in a committed and recognized union with that person, protect the integrity of their family, and participate in the society’s most basic institution (receiving its financial benefits, too, of course). These are important liberties, Kennedy says, and denying them to certain citizens based on their sexual orientation denies them the equal protection of the law.

“They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

With a stroke of his pen, Kennedy put the marriage debate in society’s rearview mirror. In doing so, though, he breathed new life into the conflict between implied rights and democracy. He found a worthy opponent in Chief Justice Roberts.

Like Kennedy, Roberts did not frame the same-sex marriage debate as one about love. He recognized what a Facebook user who puts a rainbow on his profile picture may not: Americans did not endorse same-sex marriage. The Supreme Court did. Despite public opinion polling showing that a solid majority of the population supports same-sex marriage, only 11 states and Washington D.C. had used the political process to strike down bans. Roberts sees the invocation of an implied fundamental right to marriage as expediency by the five justices who personally support same-sex marriage and wish to subvert the democratic process.

Roberts reiterates several times that he has no issues with same-sex marriage as a matter of public policy. However, he says that it is not a constitutional right, and that Kennedy’s argument that makes it so is fatally flawed.

First of all, Kennedy does not adequately address what a marriage is or what same-sex couples want. Roberts believes that there is an implied right to marriage, but it is a more limited right than Kennedy’s opinion suggests. He says marriage is, by definition, a union of one man and one woman. Indeed, all of the past cases that Kennedy used in his argument took for granted that marriage was between a man and a woman. The justices in these cases took the right to marry to mean that every person is free to enter into a protected union with a member of the opposite sex. This means that same-sex couples are not asking for a right to marry. They already have that right because they can marry members of the opposite sex. In trying to marry each other, Roberts says that same-sex couples are actually asking for a right to change a state’s definition of marriage.

Roberts also questions the soundness of Kennedy’s analysis. All four of the principles Kennedy finds could just as easily apply to plural marriages if he did not randomly insert the adjective “two” into his description of marriage. The traditional definition of marriage is a union between one man and one woman. The gender diversity requirement is effectively eliminated by the majority opinion. Only the monogamy requirement remains. Since plural marriage has deeper historical roots than same-sex marriage, Roberts wonders how the majority could uphold a ban on polygamy using the same logic.

Throughout the rest of his dissent Roberts continues to say that the right to marriage does not exist as Kennedy frames it. Instead, he believes it is being used to enact the majority’s policy preference for same-sex marriage before voters have had their say.

Social media and the wider public debate did not give much attention to the conflict between Kennedy’s implied right and Roberts’ call for democracy. Scalia, Alito, and Thomas also authored dissents that focused on judicial usurpation of democracy. All lambasted Kennedy’s implied right. None broached the subject of love. Media raved over the cherry-picked prose from Kennedy’s majority opinion, but in doing so, they avoided the tough legal questions raised by the dissenters.

Supreme Court opinions are not as glamorous as the social media glorification of Kennedy’s would have you believe. They are generally dry and tedious. But they are vastly important. Kennedy’s broadening of the implied right to marriage will affect future cases, possibly encouraging justices to rely more and more on implied rather than explicit constitutional rights. The right to privacy appeared in Griswold v. Connecticut nearly 50 years ago. It is still widely used in contemporary decisions that concern personal liberty, even if privacy is not a key issue. Clearly, judicial decisions do not occur in a vacuum. They are the child of history and precedent. Kennedy’s reasoning may affect issues down the road that are unrelated to same-sex marriage.

And what is the problem with implied rights? If justices are using them to further widely supported social causes like marriage equality, then why should we fear them?

Today same-sex marriage supporters rejoice that Kennedy expanded the right to marriage. His reasoning served the outcome they wanted. Consider other implied rights though. Champions of social progress may be less than thrilled with a state’s right to equal sovereignty that allows it to evade preclearance under the Voting Rights Act.

Equal sovereignty of states means the federal government must have compelling justification to treat states differently. It was utilized by none other than Chief Justice Roberts in Shelby County v. Holder to strike down parts of the 1965 Voting Rights Act which required several southern states to have their voting laws cleared by the federal government. The Shelby County decision allowed former Confederate states to pass new election laws that some believe restrict minority voting. These include voter identification requirements and online voting bans. Like the right to marriage, equal sovereignty among states is nowhere to be found in the Constitution.

Legal reasoning can become a dangerous thing when it becomes a means to an end rather than principle. This is not to say that implied rights are always dangerous expedients. The right to privacy from Griswold v. Connecticut is well supported by other constitutional protections and is put forth with compelling logic. But even it is not without controversy in its application. Skepticism to unwritten rights is the most prudent approach.

It is easy to forget that justices are political actors who have specific policy outcomes they prefer and sometimes will pursue at the expense of principled judicial reasoning. Kennedy, Roberts, and the rest are compelling when they explain the meaning of the Constitution. While reading their opinions, however, we should consider whether the Constitution really has a clear objective meaning or if the meaning is merely what the author wants it to be.

Proponents of same-sex marriage rightfully celebrated when Kennedy handed down his beautiful and wide-reaching decision. But do not get too lost in his poetry. The legal reasoning matters. Its implications for the future of implied rights will continue to follow us, possibly haunt us, long after same-sex marriages have become normalized. Kennedy’s opinion might encourage justices to continue to interpret the Constitution in the way that is most convenient for their politics. Unfortunately, we may not always like their politics.

That is something you won’t hear on Twitter.

By Rob Oldham/Photo Credit: MRCTV, Times Union, and Politico