By: Tyler S. Bugg

By now, in large part due to the viral social media that rocketed the news around the world, you’ve heard about Trayvon Martin’s murder. 17-year-old Trayvon was chased and shot by self-appointed “neighborhood watch captain” George Zimmerman for wearing a black hoodie, carrying a bag of Skittles and a bottle of Arizona iced tea, and “looking suspicious” as he walked through a gated suburban neighborhood in Sanford, Florida. Zimmerman claimed his actions were in “self-defense.” Police accepted his justification and opted out of administering drug, alcohol, or background checks. Zimmerman evaded an arrest, and he remains free from criminal charges or detention.

But if nothing else, he’s caught tight by the pressure of public outrage. Protests, vigils, petition signatures, and calls for justice have taken over media airwaves for days, from people of color and white people alike. The hype Trayvon’s murder has generated has moved his death away from the actual incident and closer to a protest of the marginalization people of color continue to struggle through. And white people, too, have joined the hype; violence for any person, they say, affects us all, and white people should speak out in the same way.

Yet people still claim we live in a “post-racial” society.

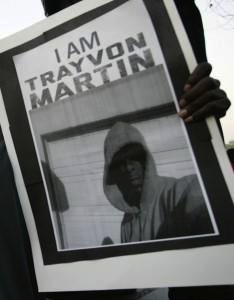

It couldn’t be farther from the truth. Following on the heels of the “I am Troy Davis” movement, the “I am Trayvon Martin” rhetoric has caught on, and like in the case of Stephen Lawrence, has quickly become the mantra that symbolizes the oppressed experiences of all people of color. The now viral mantra– “I am Trayvon Martin; you are Trayvon Martin”– is even one white people are chanting alongside (or, more accurately, over) people of color.

But not me.

I am a white man, and I benefit from it. I live a social life of (white) privilege.

I empathize with Trayvon and his family. I voice intense and critical concern for the racial violence that perpetuated his murder. But I am not Trayvon Martin.

And I won’t wear a button that attempts to (mis)identify me as such. As an individual only benefitting from long-entrenched systems of white privilege, and in the most care for Trayvon’s family, I will not don a button that implies I can somehow sympathetically relate to, connect with, or even approach understanding Trayvon’s experience. I have the privilege of having no idea of what his experience was like, and I have the privilege of knowing that I never will.

I don’t– and will never– look suspicious, and that’s the problem. I’m not going to dilute the efficacy of the movement by pretending that I do. I’m not going to wear a black hoodie or buy Skittles and iced tea to “stand in solidarity” with anyone who thinks doing so makes him or her an activist. (Does anyone remember the “slacktivism” of the much-criticized Kony 2012 movement?) I’m not going to disempower what the movement should be about.

First, what it should not be about is trendy politics. It should not be about token activism, buttons, and Facebook “likes.” Especially for me, a white male, material markers like a hoodie is hollow activism; nothing about my wearing a hoodie can be viewed as a subversive tool of protest, because I’m a white man wearing it, and my choice to do so was never questioned, never considered “suspicious,” and it never will be. It should not be about a (false) sense of pride, service, or ownership to the “cause,” and it should definitely not be about white people leading that cause, “saving” people of color from racial oppression, or “solving” the race paradigm for everyone else.

It should be about activating a more in-depth, structural, long-term dialogue.

It should be about the woman who clutches her purse when passing a person of color on a street sidewalk. It should be an ongoing discussion about normalized racism, and not only in response to the tragedies news outlets choose to sensationalize and blast across the media. (I’m equally as concerned for Shaima Alawadi and for all the other unheard-about minority-identifying people who were murdered by the violence of racism this week and did not have the same media attention to spread their narratives.) It should be about the too-legitimized institutions that perpetuate entrenched racism. It should be about removing the filters that silence the experiences of people of color. It should be about (deconstructing) the white savior industrial complex. It should be about reaching beyond the illusion that white people can forefront movements to “liberate” people of color.

I am not Trayvon Martin, but I am an ally of Travyon Martin and of every other person whose unique narrative is smothered by systems of privilege and power. I’m calling for activism that isn’t compromised by the hierarchy of power that continually fails to address it. I’m learning and listening and contributing my voice in the way I (constructively) know how, and I’m striving every day to do so out of the positive privilege of kindness and compassion. And that privilege, we all benefit from it.